The controversial chatbot was released in November by OpenAI

Feb 9, 2023

The academic world is preparing to adjust to ChatGPT, another technological advancement that has faculty and staff at SF State wondering how the new tool will fare in a classroom.

ChatGPT is a free-to-use artificial intelligence system launched by Bay Area-based startup OpenAI on Nov. 30. The program allows users to hold real-life conversations with a chatbot system programmed to accurately answer questions. The model is also capable of admitting its mistakes, challenging incorrect premises, and rejecting inappropriate requests.

ChatGPT’s success prompted other major technology companies to follow suit. On Monday, Google unveiled a similar chatbot tool of their own called “Bard,” which is expected to open up for testing this week.

ChatGPT has raised some eyebrows in different writing departments at SF State.

Brian Strang, a lecturer in the Department of English Language and Literature, experimented with the system by feeding it with questions –– many of which were unserious, a tactic he says to have used out of curiosity to determine how helpful the bot is.

The questions were highlighted in Strang’s opinion piece for Inside Higher Ed, where he pressed ChatGPT on whether it could recognize music lyrics, give dinner advice or even provide a legitimate opinion on the prospect of universal health care in the United States.

“I was just getting a feel for the algorithm and it would give me a lot of summary with a lot of boilerplate language,” Strang said. “I know that it can be finessed more than that, but you really have to work on it. You also have to have a lot of rhetorical knowledge about writing to finesse it to the point where it would produce more of a voice — more authentic-sounding writing.”

Strang notes that technology has changed the academic landscape over time, citing how modern language studies have been infiltrated with translation apps and the development of calculators has led to simpler shortcuts in mathematics. As a result, he provided ChatGPT resource links for his students to play around with the program.

A similar path has been taken by Nona Caspers, a professor in the Department of Creative Writing and award-winning author. Caspers says she remembered feeling “sad” the first time being notified of ChatGPT’s capabilities, wondering how it would affect the usage of the brain.

“To me, there’s something sacred and so mysterious about the creative process that I just don’t want to believe that AI can simulate that,” she said.

Caspers teaches a group of graduate students who are studying the art of teaching creative writing. After her class began showing interest in how artificial intelligence works, Caspers assigned the classroom to experiment with it. At a later time in the semester, she says they’ll check back in with each other to compare and contrast what they learned.

Despite the hesitation by some educators on campus, Strang says the conversation in English Department meetings has rarely been about the issue of students taking advantage of ChatGPT as a tool to cheat. Instead, they’re planning on confronting it by further pushing their students to jump ahead the curve –– and the robots.

“Too often it’s talked about in terms of students trying to get away with something and teachers policing them,” Strang said. “And that, I don’t think, is the right way to look. I think that students should think about what skills they’re going to leave the university with. If a bot can do a lot of entry-level, white collar work and writing, then students have to be able to do something that a bot can’t do. They have to be better than a bot. So that kind of raises the stakes for students. It may be able to do a lot of the drudgery of writing, but it doesn’t have a lot of originality, creativity or an authentic voice. “

Jennifer Trainor, a professor also teaching in the Department of English Language and Literature, echoes Strang’s thoughts and believes any obvious usage of AI would violate SF State’s existing honor code agreement. Trainor also expressed her desire in the academic structure to address conflicts of linguistic racism, which could put pressure on students who don’t understand English to use ChatGPT.

“A lot of students haven’t necessarily got the perfect standard English under their control and they’ll try to write things in a high stakes environment –– and they may get judged unfairly because their English isn’t perfect,” Trainor said. “So ideally, ChatGPT could eliminate that problem, but I also think that is the wrong solution to how we would go about eliminating that problem. To eliminate that problem, I would try to eliminate linguistic racism.”

According to Strang, the technology comes down to how it’s used.

“I think that it’s here to stay, but it has its limitations like any other tool,” Strang said. “If it’s a tool like a hammer and if you hit yourself in the thumb, don’t blame the hammer.”

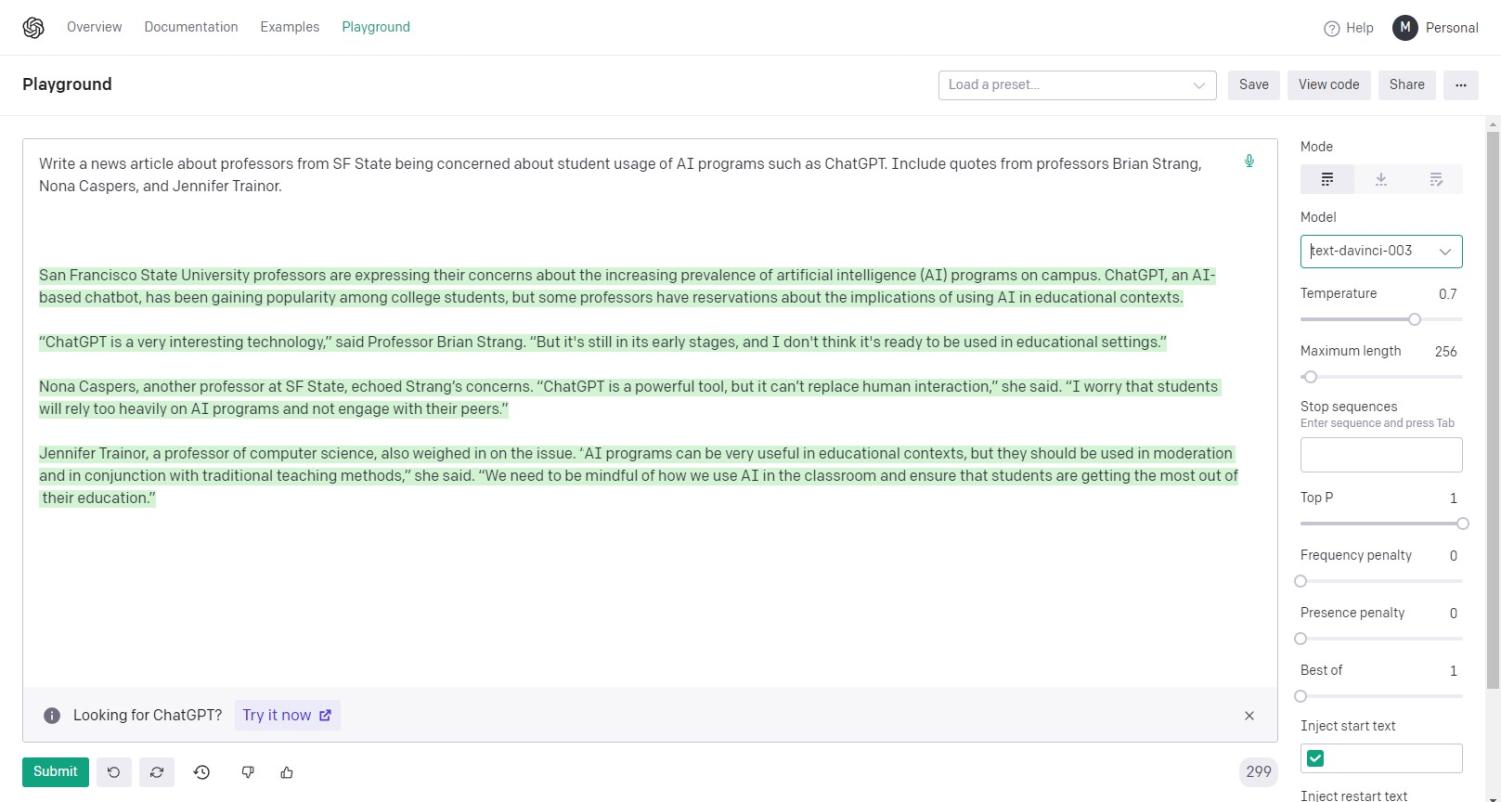

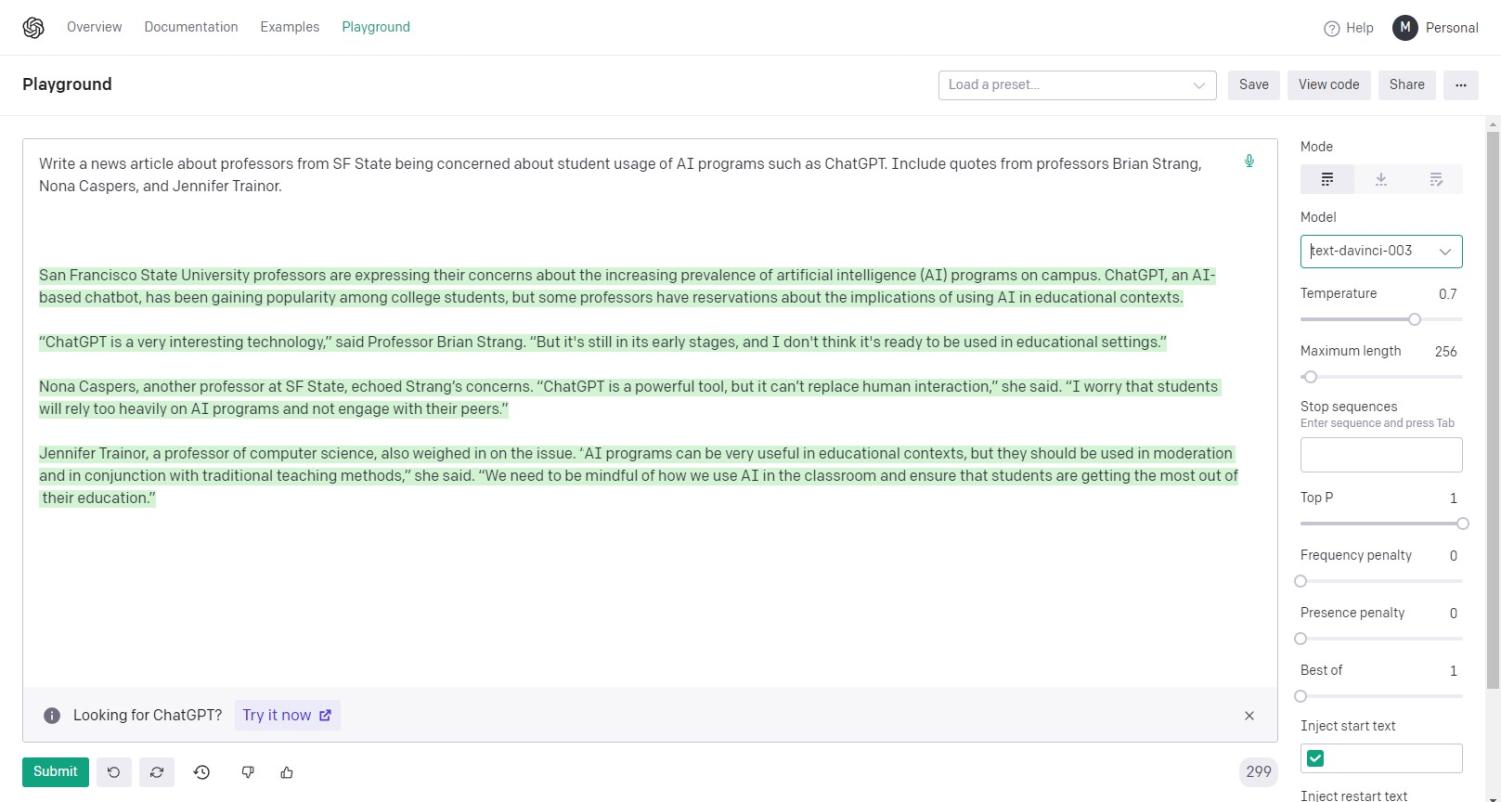

Brian Strang • Feb 11, 2023 at 9:59 am

Nice article, Steven, and interesting screenshot of ChatGPT’s attempt to write the article (I think your job is safe for now ). What would be the consequences for a (human) reporter if they were to make up fake quotes and attribute them to people as ChatGPT does? I’d be interested in hearing what the Journalism department has to say about this.

). What would be the consequences for a (human) reporter if they were to make up fake quotes and attribute them to people as ChatGPT does? I’d be interested in hearing what the Journalism department has to say about this.