Members of SF State’s Africana Studies department reflect on the recent ban and changes made to African American studies curricula

Feb 22, 2023

From fall of 1968 to spring of 1969, SF State students and supporters marched across campus daily with placards and their fists held high in the air.

“On strike! Shut it down!” They chanted in unison.

When the Black Student Union’s set of demands to fight racism and to aid in the development of Black education were not met by the university, they launched the Third World Liberation Front. Asian and Latinx students joined BSU in demonstrations with walkouts, rallies and protests.

The 115-day strike was ultimately deemed successful on March 20, 1969. That fall, the College of Ethnic Studies at SF State was established.

Meeting the demands of the BSU, the Africana Studies Department (formerly known as Black Studies Department) was implemented, allowing Black history, ideas and concepts to be taught from the Black community’s perspective.

Africana Studies has since been a source of pride for SF State due to being the first of its kind. It is celebrated by the campus and open to all students. This is a stark contrast to many educational systems across the United States, as Black and African American studies have been constant targets.

Earlier this month, Florida Gov. Ron De Santis blocked Florida high schools from teaching the College Board’s new advanced placement course in African American Studies.

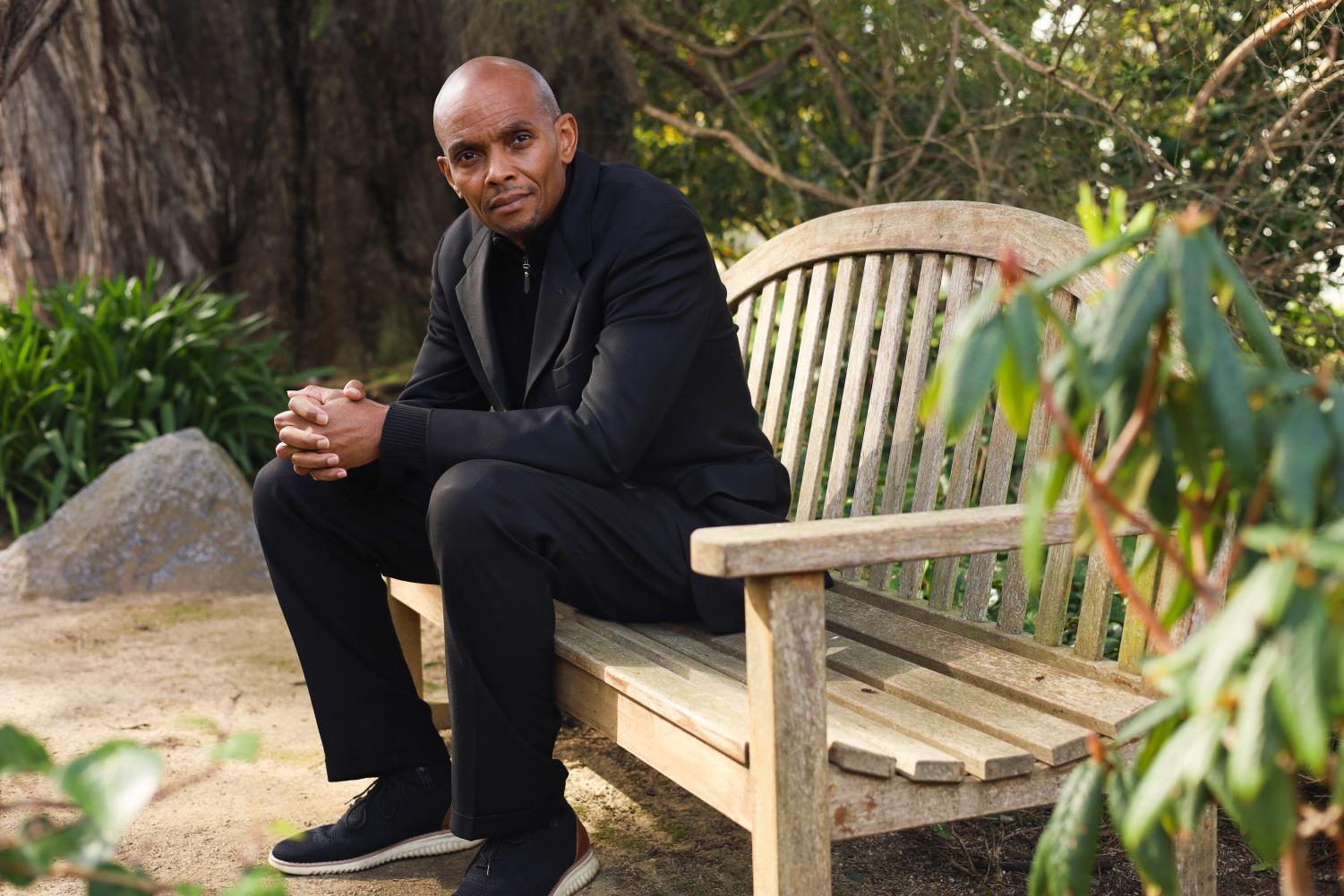

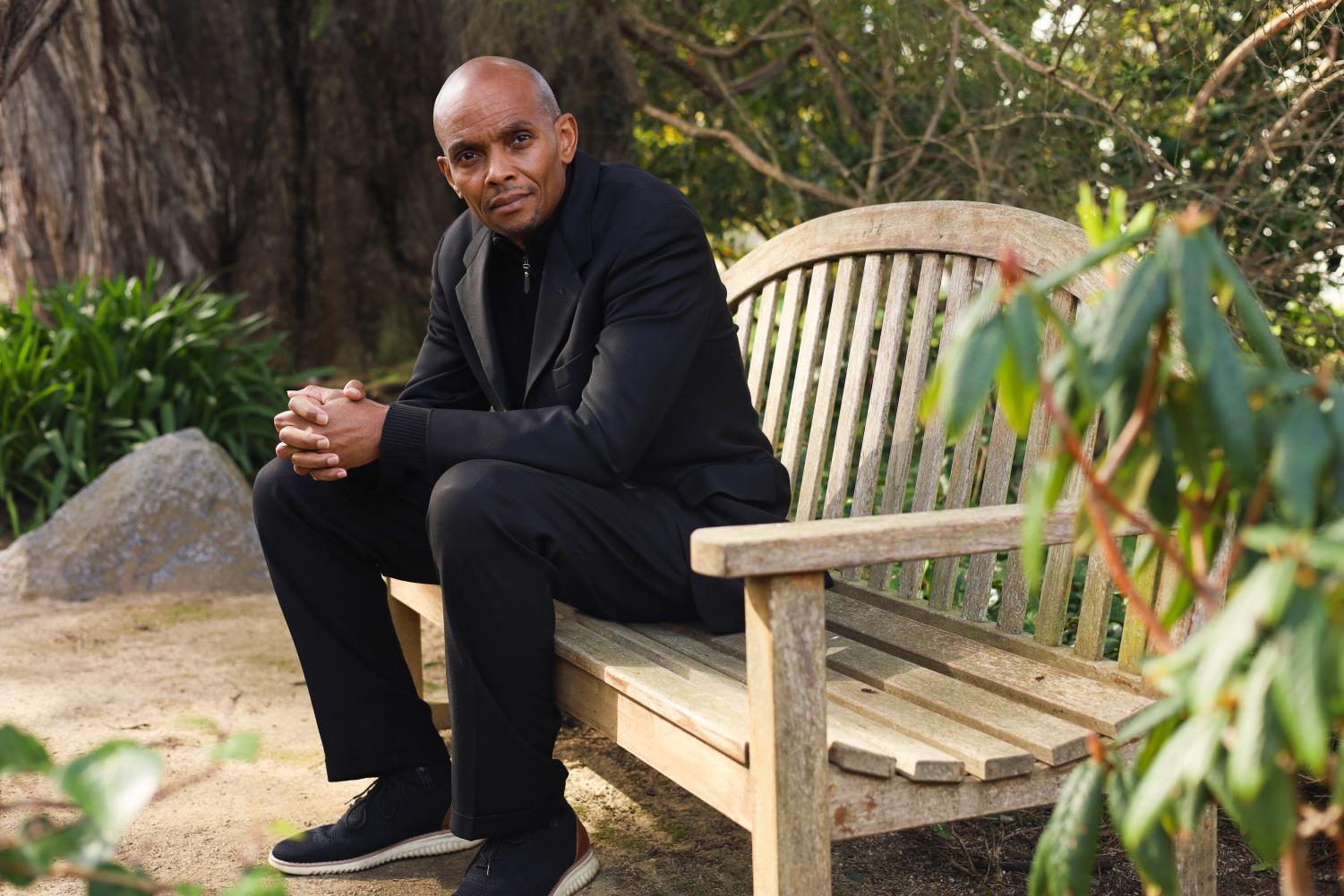

Professor and Chair of the Department of Africana Studies, Abul Pitre, has been teaching African American studies since the 1990s. He got his start as a high school social studies teacher when he worked closely with young Black men who engaged in territorial fights.

When students’ grades improved and fights were no longer prevalent, Pitre was asked to take charge of the school’s Black History program, but was soon met with pushback.

“The program became controversial because one of the White teachers in the program called the school board about a fight,” Pitre said. “Eventually it created other problems and I was transferred from the school. I started to realize there are certain things that you couldn’t teach in schools that would awaken the consciousness of students, things that students would want to know are left out of the curriculum.”

Pitre sees the political rhetoric regarding Black studies as an attack on education.

“When we begin to look at the idea of critical race theory and the ban on it there’s really some distortion where they are trying to cut out multicultural education,” Pitre said. “They skillfully use the term critical race theory because, if they recognize, if they use multicultural education people would push back.”

As reported by UCLA school of law’s CRT Forward Tracker, almost a quarter of states have made laws against the teaching of critical race theory.

Damarcus Johnson, a fourth-year History major with a focus on Black literature, was exposed to Black history at a different level when he enrolled in an Africana Studies class in college.

“It was a level of exposure to Black history that I really hadn’t gotten in high school,” Johnson said. “We weren’t just talking about slavery or civil rights as this thing that had happened and was over. We were examining resistance to systems that were put into place by American society.”

Johnson found the Black Studies course to be an eye-opener.

“To me, Africana Studies isn’t just Black history in the sense of recounting historical events, it’s examining resistance as well,” Johnson said. “When we look at Black history through the lens of American history, it’s usually the narrative of Black people were slaves, we freed the slaves and reconstruction happened, then Jim Crow and civil rights happened, then racism is over.”

Africana Studies professor and alumna, Dorothy Tsuruta, has been teaching at SF State since 1997. To Professor Tsuruta, Black Studies is Black people speaking for themselves.

“Today, there are organizations that represent people speaking for themselves, about themselves and we have been denied that. We have been studied by other people,” Tsuruta said. “Even in my all-Black high school in Chicago, they were still educating us with a White curriculum and White voices talking about Black people.”

Tsuruta gives all the praise and thanks to the BSU of 1968 for their fight to establish Black Studies at SF State.

“These were students who inherited the fight of the Martin Luther Kings, of the Carter G. Woodsons, of the Ida B. Wells, of the Harriet Tubmans,” Tsuruta said. “We’ve always had Black people speaking for ourselves and doing for ourselves but it hadn’t come to the school in that way. It is very important now that we don’t allow the work of the 1968 BSU to be undone.”