Black and Latinx student enrollment and retention rates continue to decline at SF State

The enrollment and retention gap for Black and Latinx students persists and the university is taking initiatives to eliminate it.

May 17, 2023

Five decades ago, at what was formerly known as SF State College, a revolution took place.

At the time, SF State’s student body was made up of only 7% students of color, and only 3% were African American. Searching for equal education opportunities for Black students, SF State’s Black Student Union demanded more enrollment slots and active recruitment; however, the administration pushed back.

From November 1968 to March 1969, students disrupted campus life at SF State, marching with picket signs in hand, their fists held high in the air ––chanting in unison to demand significant change at their institution. Led by the BSU of 1968 students and supporters went on a 115-day strike, the longest student-led strike in American higher education history.

Receiving national attention, the revolution was televised as even government interference failed to shut down the massive demonstration. Five months after the BSU’s first efforts toward systematic change at SF State, the strike officially ended on March 20, 1969. In the fall, San Francisco State College officially established the first-ever College of Ethnic Studies. In its first year, about 200 students enrolled in the college.

Today, enrollment in the college is over 6,000 — but the current students the strikers of the TWLF fought so hard to create a space for often struggle to graduate from the university or drop out altogether year after year.

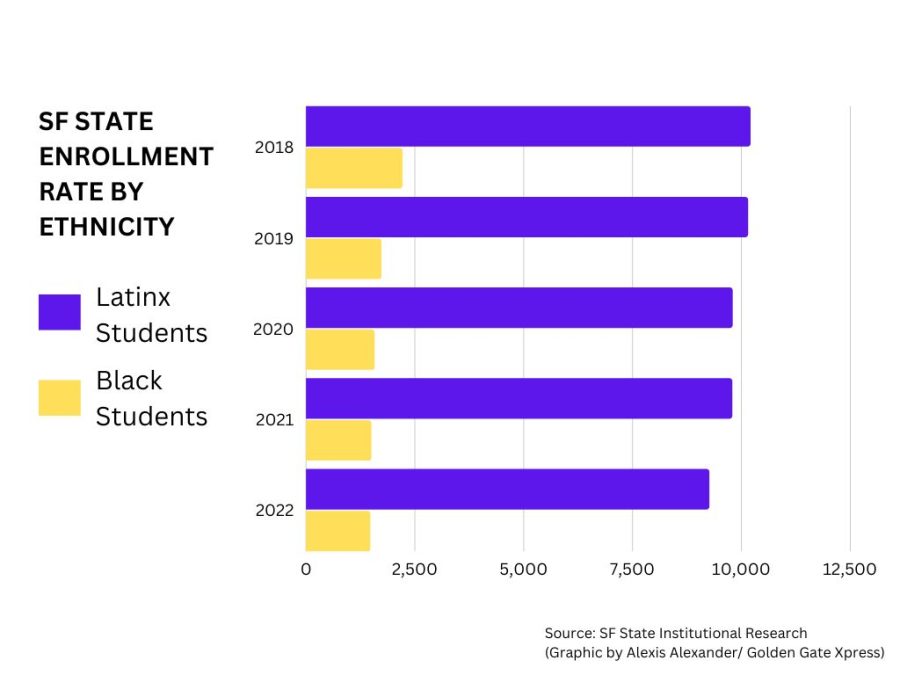

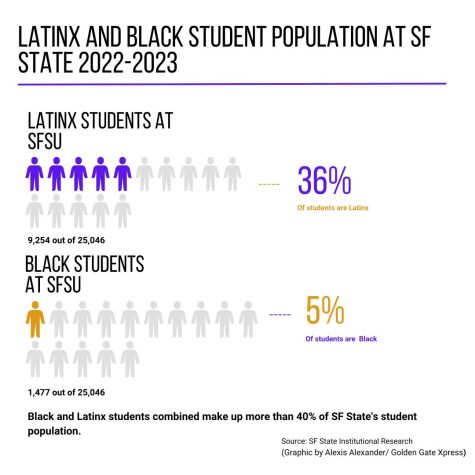

Black and Latinx students combined currently make up almost half of SF State’s student population with 1,477 Black students and 9,254 Latinx students enrolled, but these numbers continue to dwindle annually.

In a campus-wide email sent by SF State President Lynn Mahoney last spring, SF State statistics showed that only 67% of Black and Latinx freshmen who entered in Fall 2019 continued their education into Fall 2021.

According to SF State’s Overall Tracking Report, enrollment for Black students has seen about a 14% decrease since 2019, followed by an almost 9% decrease for Latinx students.

Despite some exacerbation due to the pandemic, the issues that continue to create a downtrend in retention and graduation for these two student demographics are not new.

Cost of living and housing

Larry Salomon, a senior Race & Resistance lecturer and alumnus, has been teaching at the College of Ethnic Studies for almost 30 years. A majority of his students have been Black and Latinx.

“A lot of what has changed our enrollment, especially for Black students and local Latino students who grew up in San Francisco, is a lot of those folks have been pushed out of San Francisco and Oakland,” Salomon said. “We’ve lost a lot of those students and those families because of gentrification and affordability issues in the Bay.”

When Daniela Haro enrolled in the Broadcast and Electronic Communications Arts department in Fall 2020, she anticipated completing her degree in four years. When her first semester was moved online due to the pandemic, Haro found herself navigating enrollment, housing and financial aid all on her own with little to no knowledge of what she was doing.

“Everything was online — advising, orientation, all of that — so it was a bit difficult navigating college,” Haro said. “I’m first-gen, so the whole experience I was just on my own trying to figure out who to talk to. I never really knew what resources or who to reach out to in order to figure out classes or housing.”

Following an extensive search after her on-campus housing plans fell through, she was forced to stay home in Whittier, setting her back a semester.

“I ended up not getting housing for the fall semester,” Haro said. “I had already selected classes that were in-person, but by the time I figured out I needed to switch to online, they were already closed.”

Haro, now a junior, lives in the city, but found it difficult to find adequate off-campus housing.

San Francisco’s housing crisis can greatly affect SF State students’ college experience.

On-campus housing, provided by the university, is mostly catered toward first-year freshmen. Out of the eight on-campus housing buildings currently open to students, only three offer housing to upperclassmen.

As of April 2023, the median rent in San Francisco for a one-bedroom apartment is $3,000. The median rent for SF State upperclassmen housing is $1,617, but that does not include the additional off-campus living costs such as food, utilities and commuting. The median rent for first-year students is $1,269, which requires a meal plan and is paid in a set of installments.

Lack of communication and outreach

2021 census data found that only 11.5% of SF State students are residential, while the remaining 88.5% commute.

Jocelyn Olide, a transfer student, found that the commuter campus can sometimes lack a sense of community for students. When she shared this with a colleague, they recommended she check out the new Latinx Student Center.

It opened up a new world for her.

“I started going there and it just felt like home, I felt very supported. The students there just represented what it means to be first-gen Latinx students,” Olide said. “But, I think unfortunately that was something that I had to go and dig up and find myself.”

Another issue students may face is not knowing who to contact for a particular issue. Campus resources, academic or simply for students are not always well promoted by the university.

Similar to Haro, fifth-year psychology major Giovanni Aragon felt alone in his academic planning during the pandemic.

“When I was on campus I felt supported, but during the pandemic, I felt like it was hard for them to show support,” Aragon said. “It was hard for me to know what classes to take, it was hard to reach a tutor or an adviser.”

Aragon found advising and enrollment difficult during his first few years at SF State, especially when prerequisite classes for his major would fill up.

“If you weren’t able to get that one class, they kind of just let you fend for yourself and figure it out on your own,” Aragon said.

Financial Aid

Africana Studies Department Chair Dr. Abul Pitre has seen the difficulties of navigating financial aid negatively impact Black and Latinx students’ academic success.

“Factors like financial aid, once they get into the university, they have trouble navigating,” Pitre said. “I see students all the time that might enroll, then they [get] financial aid problems and nobody is there to deal with it.”

According to SF State’s Strategic Enrollment Management plan, 71% of full-time undergraduate students receive some sort of need-based financial aid and 62% receive financial aid in the form of grants.

Michael Apalategui was a mechanical engineering major who attended SF State from 2019 to 2021. After his freshman year, he was no longer eligible for financial aid .

“At the end of 2021, I had moved back up here and just financially I wasn’t able to do it anymore,” Apalategui said.

Apalategui did not find any solutions from SF State for the financial issues he faced. Eventually, Apalategui left the university to work full-time to support himself

“I didn’t get any help and financial aid thought my parents could support me but they couldn’t,” Apalategui said.

In the last decade, college tuition fees have seen a significant rise. In College Board’s Trends in College Pricing Report, the average price for tuition at a four-year, in-state university is $10,950.

Although SF State’s tuition is $3,000 lower than most universities in the nation, the cost of living in the city is 79% higher than the national average.

Victoria Bell, a third-year communications major, received full-coverage financial aid for their first two years at SF State, but was no longer eligible due to a tax claim mistake. To receive aid they had to petition the claim, which was not a simple process.

“The financial aid department was so unhelpful,” Bell said. “It was a lot of like, ‘go to this person, go to that person.’”

Bell’s petition was accepted and they were able to use financial aid to cover this semester, but were stripped of aid once again for the upcoming fall. Bell juggles multiple jobs to cover tuition and housing fees all while attending school full time.

“Right now, I have two jobs and I’ve been juggling between two to three,” Bell said. “Doing those with full-time school is really hard. I feel like depending on what kind of professor you have, your academics can then plummet because you’re being forced to work so hard to afford the living expenses.”

Some students have trouble navigating financial aid and cannot reach the correct campus resources when they attempt to.

Haro also found the financial aid process to be unclear.

“I think my biggest struggle when it comes to college has been financially because I don’t know what I’m doing when it comes to financial aid,” Haro said. “Every time I would call the Financial Aid Office, there would be long wait times and nobody was really helpful. It was never ‘here’s this resource, here’s what you can do for this’ — no help other than ‘this needs to be paid.’”

Just this year, the U.S. Department of Education announced a redesign that is meant to simplify the FAFSA application, which will be released in December 2023.

Another issue students face are holds on their virtual Student Center. These holds include “Student Financial Obligation,” or an S2 hold which only allows students to enroll in courses when their past due amounts are paid in full.

Aragon also found himself unable to enroll for the upcoming fall when there was a prior summer hold on his student account.

“I had a hold and wasn’t able to sign up for my classes,” Aragon said. “It caused a lot of stress and I wasn’t really able to figure out what I was supposed to do for that year. After I was able to pay the fee from summer school, I was able to get my classes, but had to sign up for classes that weren’t for me, so it put me more behind for my prerequisites for my major.”

According to SF State’s Bursar’s Office student inquiries page, students can simply pay their past due obligations to release the hold; however, there are no resources listed for students who may need more time or help to gather the money they owe.

In some cases, students who saw a hold simply did not enroll in courses due to a lack of knowledge on which university resource to contact.

Katynka Martinez, interim dean of the College of Ethnic Studies, received a list of students who completed coursework but did not enroll to continue in the upcoming semester. She, along with other associate deans, reached out to these students personally.

“We made phone calls just to reach out to those students directly and some of the students just didn’t know what had happened,” Martinez said. “They had tried to call financial aid or the registrar and just had a hard time navigating the system.”

Martinez had seen students like Aragon, who also had difficulties working through a block on their enrollment.

“Sometimes they had a block on their enrollment, or they thought they had a block but they didn’t have a block,” Martinez said. “I think that personal touch just made a big difference.”

Closing the gap

Last fall, SF State implemented the Strategic Enrollment Management Plan which was created by Mahoney’s Strategic Advisory Committee and first introduced in 2019. The plan’s main goals are to support enrollment growth and sustainability.

Outlined in the SEMP, SF State’s retention strategy is to “establish clear set targets for all student groups, identify student challenges, and opportunities to coordinate retention efforts.”

Staff and faculty are expected to play key parts in committees executing the plan.

Programs at SF State like the Metro College Success Program primarily focus on students’ first two years at the university. Martinez suggests initiatives that continue to guide and support students in their third year and beyond may aid in helping them navigate college on their own, which could lead to higher rates of degree completion.

“We put all this effort in at the beginning, we don’t really have too many things in the middle,” Martinez said. “Just checking in with students on a more consistent basis, because I feel like they can get lost between when they get that focused attention and then when they graduate.”

Rama Kased, assistant professor and co-founder of METRO, finds building community and long-term student relationships as a key factor of student retention.

“What I learned early on is that our wealth doesn’t come in monetary [terms], our wealth comes from building community and social networks,” Kased said.