San Francisco State University celebrated 236 years since the United States Constitution was signed into law and hosted Constitution and Citizenship Day conferences last week.

The conference also commemorated the 50th anniversary of the 1973 landmark case San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez, which ruled that there was no constitutional right to equal education, but public schools could be funded by property taxes.

Constitution Day is a national holiday commemorating the signing of the Constitution on Sept. 17, 1787. Since SFSU is a state school that gets funding from the state, the school is required to celebrate the holiday according to the California Department of Education.

Marc Stein, a history professor at SFSU and conference coordinator, invited speakers to come and share on topics like abortion, rights to education, indigenous rights and anti-Blackness and the law in the making of Jim Crow policies.

“I’ve been running the conference since 2015,” Stein said. “I very much wanted to put a social justice spin on the conference and focus primarily on critical perspectives on the history of the US Constitution. So I think this year’s program really did that and has been the case for previous sessions.”

Rachel F. Moran was one of the keynote speakers this year. She is a law professor at Texas A&M University School of Law. Moran’s presentation focused on the right to education, the disparity in education between students at public and private institutions and the San Antonio Independent School District v Rodriguez case.

“At the time that Rodriguez came through, children generally, overwhelmingly, were attending public schools,” Moran said. “They still do. But there has been a strong movement to privatize education, through choice.”

Privatization of public education refers to schools contracting private, for-profit companies for soft services such as administration and instruction.

“Privatization is a way to let people kind of go into their silos through choice, and not have them all together in that common school fighting over what gets included in the curriculum,” Moran said. “The other potential reason which comes up, and it was interesting because it came up earlier today, is that teachers’ unions have been heavily Democratic and pretty successful. And there’s a feeling among the Republican Party that by privatizing the schools, you break the teachers’ unions.”

With public schools competing with private schools, higher education tuition costs grow. Since private schools control where their money goes, they often have newer resources than public schools.

“I’ve always loved public schools, I really believe in public schools,” Moran said. “One of the happiest things for me when I was in Berkeley Law was to see these families come in from very humble backgrounds for graduation. We didn’t care who could come –– you get to come. And to know that we had made this tremendous difference, not just for one student, but for the whole family. It was like a family accomplishment. And it’s harder and harder for that to happen.”

(Andrew Fogel)

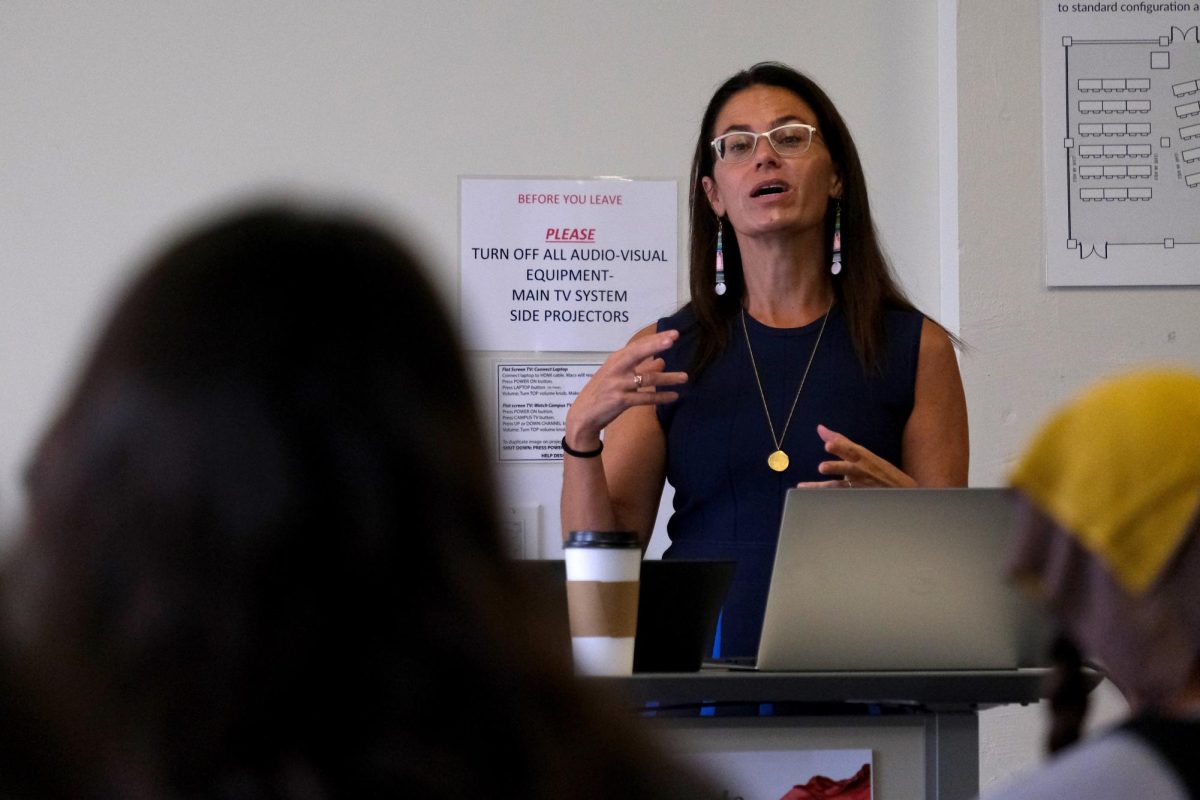

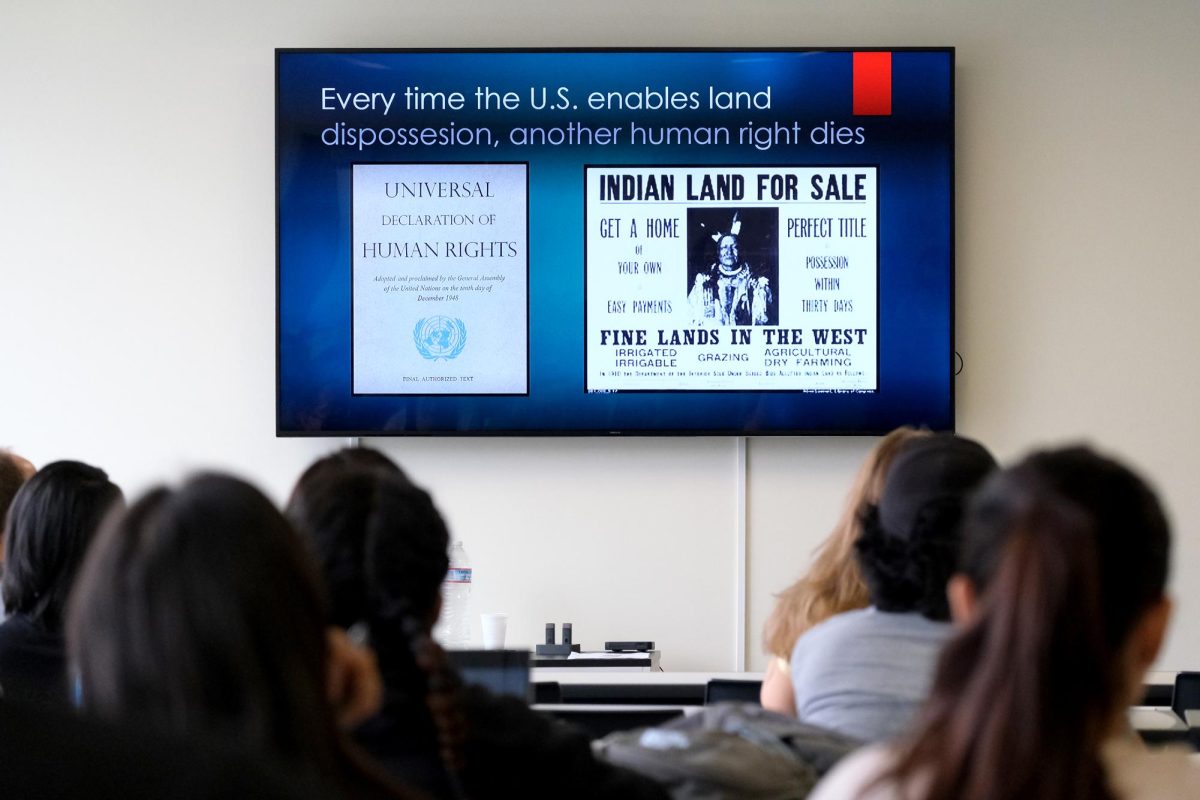

Kristen Carpenter is the Council Tree professor of law and director of the American Indian Law Program at the University of Colorado Law School. Carpenter spoke at the event about Indigenous lands and human rights in the United States.

“Human rights, the norm that we all think we’re living by, is that all human beings are born free,” Carpenter said. “But when it comes to some of our most fundamental rules and laws and norms in the United States, like the government will protect our property or that we have property rights, it doesn’t apply to American Indians.”

The First Amendment gives Americans the freedom of religion, but not for Native Americans. In cases regarding sacred land, the federal government took the land from the Indigenous without regard for their religious practices.

“We [America] love religion, we love religion so much it’s become like a super right, except in the case of American Indians,” Carpenter said. “The First Amendment basically doesn’t even apply in American Indian cases.”

Margot Lipin, Mario Burrus and Tara Madhav are all doctorate students at UC Berkeley. Their topic compiled anti-Blackness and the law in the making of Jim Crow policies. Lipin’s presentation covered white supremacy, violence and liberalism in the 1876 U.S. v. Cruikshank case.

“Given their new rights for the revenue rights of free people to vote by free people, and the borrowing from office of former Confederates, hundreds of Black free people were elected to political office, ranging from local magistrates and sheriffs to congressional representatives,” Lipin said. “As a result, white supremacist organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan, emerge to terrorize Black free people and restore white political hegemony in the South. And so, radical Republicans in Congress became concerned about this rise in anti-Black terrorism, not only for the threats against the lives of Black people, but also the threat to Republican political control. The KKK was aligned with the white Democrats. And so they targeted not only Black, mostly Black individuals but also Republicans.”

Burrus is an SFSU alumnus. He got his undergraduate in Africana studies and history and his presentation covered Plessy to Loving and the legal fallacies of Jim Crow laws.

“I want to start by saying that writing critically about racial classifications is challenging because of the risk that any invocation of a racialized group such as Black, African American, [American] Indian, might be interpreted to imply support for essentialist and biological notions of race,” Burrus said. “Thus, I want to make certain, be very careful when using contemporary racial terms to describe people to the past who did not identify themselves by these very imprecise terms.”

Madhav’s presentation talked about criticisms of the private and public distinction in Black radical thought. Public groups are seen as associated with government entities whereas private ones are seen dealing more with companies and non-government affiliated organizations.

“The public, which has now given itself the ability to legalize discrimination, is propping up the private by only addressing cases of segregation that clearly fall under their purview,” Madhav said. “Private discrimination and segregation can exist without the approval and facilitation of public factors. And so this is a legal codification of this kind of regime of private discrimination.”

Radhika Rao, a professor at the UC San Francisco College of Law, closed off the conference with her presentation titled “America’s Abortion Theocracy.” Rao’s presentation took a deeper look into what different religions think about abortion and whether it’s considered acceptable or not.

“I actually happen to get a panel with Rabbi Barry Silver who suggested that it was not just abortion that was permitted under Jewish law, but his interpretation was it was actually mandated under certain circumstances under Jewish law,” Rao said. “So that would seem to contradict the religious beliefs at least have some and the Supreme Court doctrine on religion has been that religions get to say what their religious beliefs are. Outsiders shouldn’t be saying what their beliefs of the religion are.”

In her presentation, Rao showed that 74% of white evangelical Protestants believe that abortion should be illegal. Other groups’ percentages varied in opinions, but the evangelical Protestants held the strongest anti-abortion sentiments.

“How does one narrow religious sect get to impose their religious beliefs upon the rest of a country, or the rest of the state, in particular drag that state laws, when the state itself is religiously plural,” Rao said. “That does seem to violate the idea of this wall of separation between Church and State. But I think their response would be that we’re not imposing our religious beliefs, we’re imposing our values. And if our values come from religion, that’s not imposing religion.”