As a visual art, comic books have always been inaccessible to the blind and visually impaired. Over 7 million Americans are blind or have vision loss. That is 2% of the total U.S. population that cannot read or interact with this medium. With accessibility at the forefront of social discussion, the comics industry as a whole has not made any strides toward including this group of people, until now.

Nick Sousanis, a liberal studies professor and head of the comics minor, and Emily Beitiks, interim director of the Paul K. Longmore Institute on Disability, have adapted comics for the blind. They are working with a production company to create audio descriptions for Sousanis’ graphic novel, Unflattening, as a proof of concept.

Beitiks and Sousanis, as a part of the Accessible Comics Collective, have been working with the International Digital Center (IDC) to turn a small portion of Unflattening, Sousanis’ dissertation, into a published graphic novel looking to find the best approach for this task.

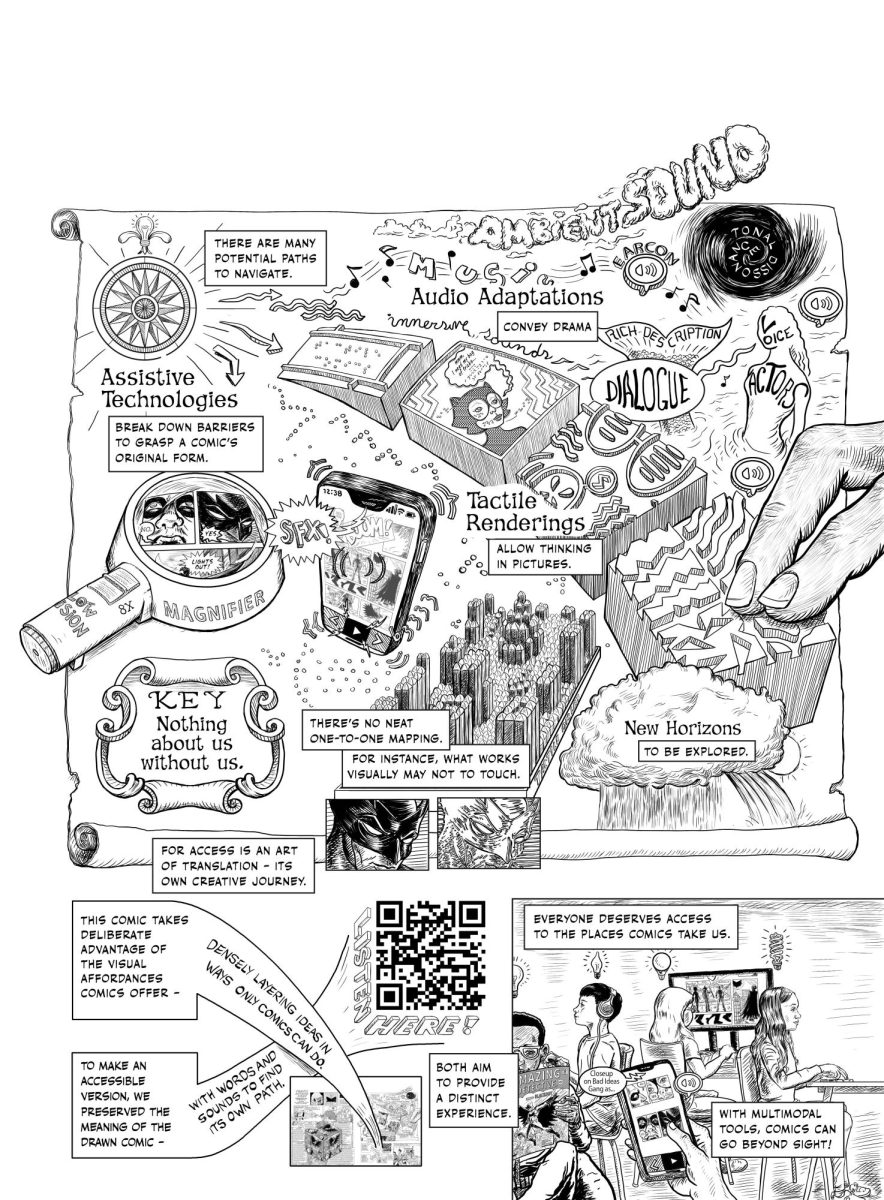

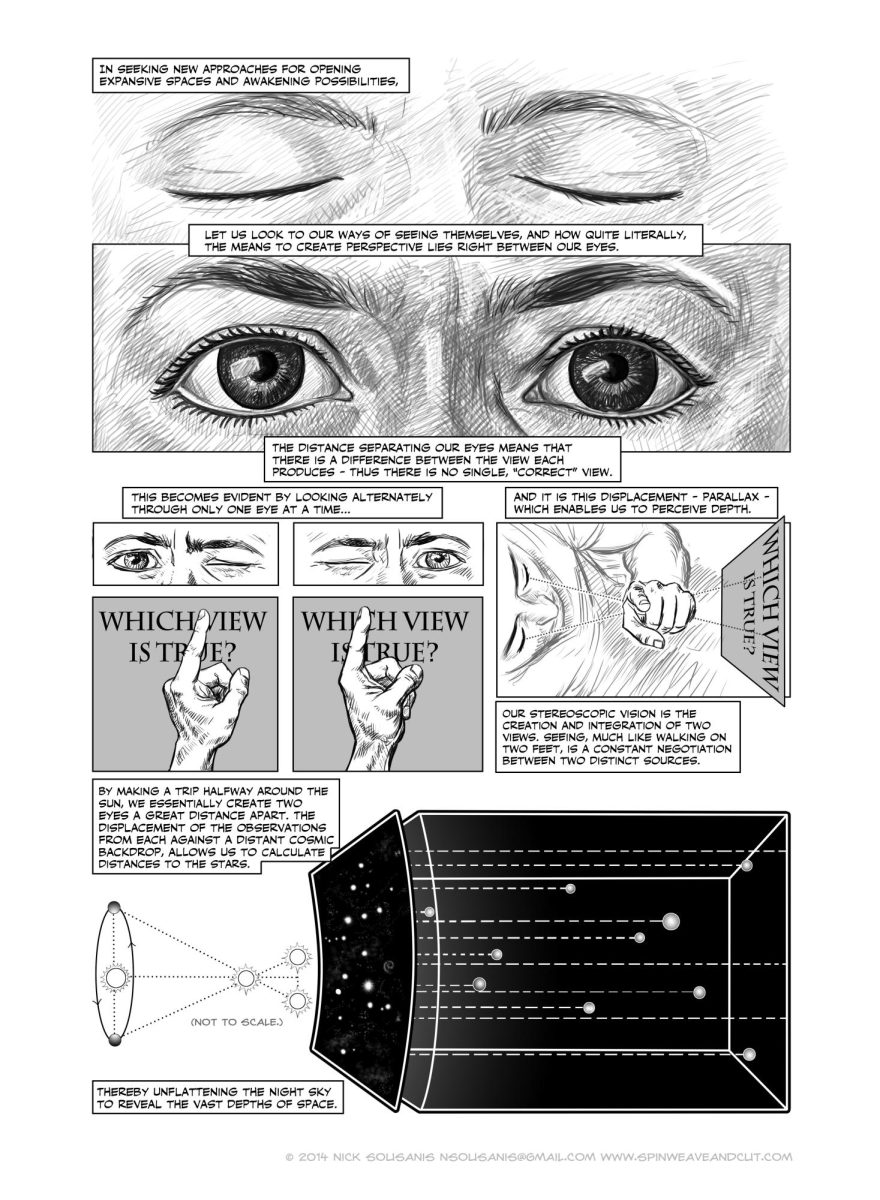

“I think the comics project starts with an intellectual question of like, ‘How do you take an incredibly visual-centric medium, and make it accessible to blind and low vision readers?’” said Betikis. “How do you take this visual medium and translate it into another realm, and yet still own proper respect for what the medium is.”

Sousanis and Beitiks assembled a team of experts to consult on how best to approach this. The team of experts consists of Scott McLead, author of Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, Joshua Miele, McArthur Genius Grant recipient, Sylvana Rainey, owner of Adaptive Technology Services and Thomas Reid, host and producer of Reid My Mind Radio and Audio Description Narrator.

This group of experts put together a competition to see what people could come up with. They saw a variety of entries, from a comic with braille in the shape of a Mobius strip to audio descriptions of comic books. In the end, this led to Sousanis and Beitiks trying their hand at making comics accessible.

“My old work was about making ideas accessible using comics. But in doing so, I leave out anybody who’s not sighted or of limited sight,” said Sousanis. “So how do we get over that?”

When Sousanis worked on his dissertation, he became acutely aware that its purpose was access. In its form, it inherently left out an entire group of people, the blind and low-vision community. This was underscored by a friend of Sousanis whose husband was blind.

While both of Sousanis’ friends supported his work, he was acutely aware that inherently, one of them was excluded from his work due to the visual nature of comics.

Today, Sousanis and Beitiks are working with IDC to produce an audio description for ten pages of “Unflattening,” due to the complexity of the drawings and layout on the page. This process will take time.

“Nick has a graphic novel that he has written and illustrated and they wanted to pursue the idea of turning that into what they’re calling the audio description track,” said Eric Wickstrom, director of audio production at IDC. “It’s just an expanded audiobook…

It’ll be the text of the book, along with detailed descriptions of each illustration on every page.”

According to Wickstrom, this is mostly a proof of concept. It will also serve as a way for IDC and the ACC to understand best practices for approaching this process moving forward.

The assigned production will not conclude until after early 2024. Afterward, the two groups will meet and make plans to move forward.

The road to accessible comics looks to be a long one. While Sousanis and Beitiks continue to work on bringing these pieces of art to those who cannot benefit from them since their inception, others may join them in their journey. For more information, reach out to the Longmore Institute.