The holiday season is in full swing –– the number of parties and gatherings to prepare for is increasing and students across San Francisco State University are firing up the stove.

During holiday festivities, students eager to make an impression grapple with the decision of which produce to purchase. Many may feel enticed to opt for organic options as they strive to be more mindful of their food choices. But the term “organic” can be complicated to understand.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture’s Agricultural Marketing Service, there are four different organic labels for produce alone: 100% organic, organic, made with organic — and specific ingredient listings. So what differentiates them? What is required to earn that organic certification and what do you have to know about organic food to make more educated consumer choices?

According to the USDA, all organic produce –– no matter the distinction on the labels –– must follow the same basic requirements. All products must:

Be monitored by a USDA NOP-authorized certifying agent

Be produced without using prohibited methods

Be produced without using prohibited substances

Gretchen George, an SFSU associate professor, said that an NOP-authorized certifying agent conducts inspections to make sure the production of organic products follows USDA guidelines.

“It means that someone’s going to test your soil. They’re going to test your methods, they’re going to evaluate you; probably walk around your farm,” said George, who is also the co-program lead for SFSU’s Family Interiors Nutrition & Apparel Department. “They’re really going to maybe even test the product for levels of anything (and see if) there’s a concern.”

Fellow professor of nutrition and dietetics, Zubaida Qamar said that, unlike conventional production, organic farming methods “foster resource cycling, that promote this ecological balance and that enhances, or at least maintains, the soil and water quality and minimize the use of certain synthetic materials and (promotes) biodiversity.”

The USDA website has categorized prohibited substances into the categories of crop production, livestock production, and organic handling production. The website says that in crop production, any synthetic substances are prohibited unless specifically authorized.

Anjuman Shah, the resident dietitian at Health Promotion & Wellness nutrition clinic, elaborated on how prohibited substances affect crop production.

“Some of these prohibited substances are,essentially, things that are being added — synthetic items, things that are man-made — that are being added into the soil to help enrich the size of things that are being grown,” Shah said. “But those chemicals that are being added aren’t necessarily preserving the quality of the soil.”

These baseline requirements are required for all organic product labeling. According to George, the difference between the labels comes down to how much of the production process meets those standards.

“The labeling to be 100% organic and having that confidence of a consumer, that comes with a cost to the company and to the person having to come in and prove that everything truly is 100% organic,” George said. “So I bet they go that distinction because there are different levels and it takes time.”

100% Organic

“100% organic means that every single ingredient used to make the product used organic farming practices, meaning that they used more natural pesticides or natural chemicals or less chemicals compared to conventionally grown things,” Shah said. “So every single ingredient in that food, like the smallest ingredient, is going to be organic.”

The USDA website adds that most crops, if raw and unprocessed or minimally processed, can be labeled 100% organic.

Organic

While 100% organic produce follows USDA guidelines exactly, produce labeled “organic” is less exacting.

“The label organic basically means a product that contains a minimum of 95% organic ingredients,” Qamar said. “Which basically means that the 5% that’s remaining, that could have other nonorganic ingredients.”

Qamar said that nonorganic processes and ingredients may be used in production, as long as the product meets the baseline 95% organic certified requirements.

Made with organic —-

“’Made with organic’ basically means the product is going to contain at least 70% organically produced ingredients,” Qamar said. “And when we talk about these ingredients, they typically exclude water and salt.”

Specific ingredient listings

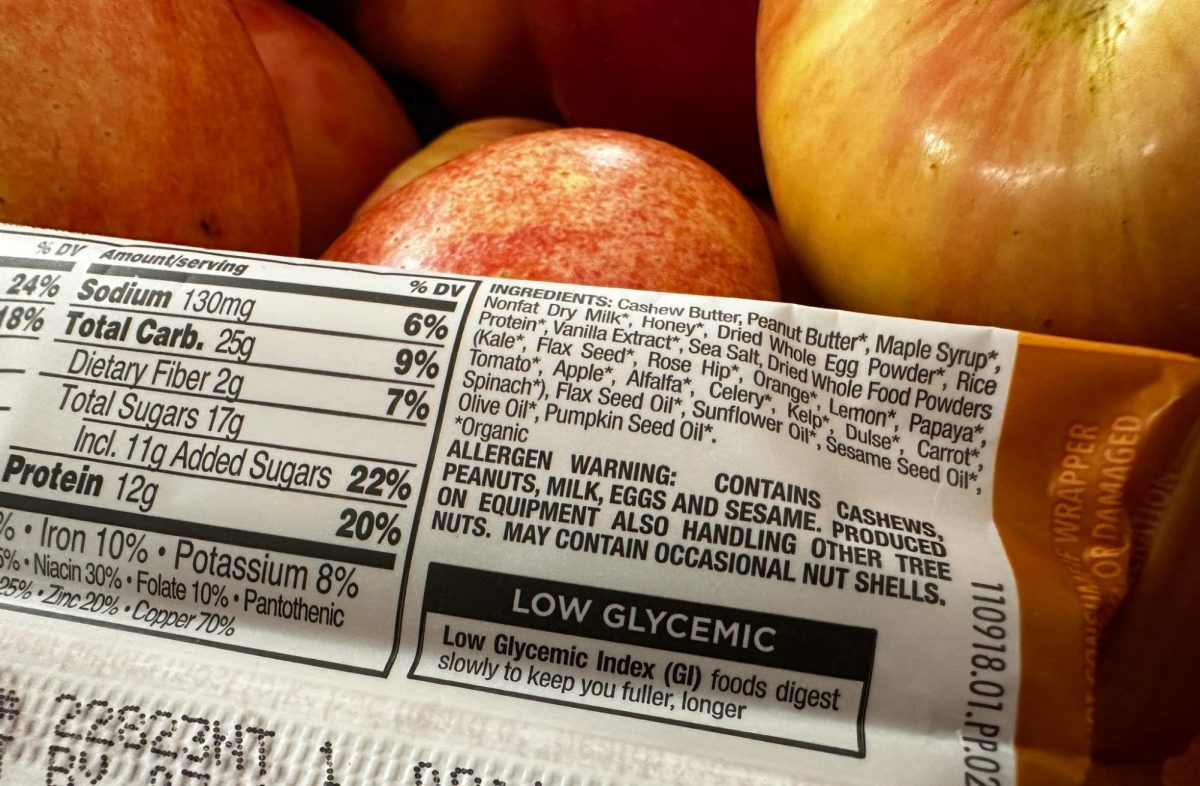

Of the different labels, specific ingredient listings feature the least organic production methods, and the labeling is meant to reflect that. According to the USDA, specific ingredients are listed on a product that contains less than 70% organic ingredients or methods.

“If they use specific organic ingredients, right they will mention those, and it’s for a consumer to be aware; and also from a marketing standpoint, (it says) that ‘Oh, our product contains, you know — our granola bar or whatever we were producing — It contains specific ingredients that are organically produced,” Qamar said. “And for some people, it could be an indicator of quality.”

Debunking the myth: organic equals healthy?

But it’s not only the different, often confusing produce labels that make barriers to food and nutrition literacy. Shah, Qamar and George all agree on one thing — they’ve seen a wealth of misinformation regarding what organic means.

According to Shah, people have increasingly equated organic to being healthy. In reality, said Shah, the term “organic” doesn’t refer to the nutritional value of food at all, but rather the method of production.

“People have interpreted organic as being synonymous with health, and kind of [ask] if a food is healthier or not for you,” Shah said “But in fact, organic is actually referring to a farming practice. It’s not a health claim.”

Beyond superficial differences, like a brighter color or smaller size, the nutritional composition of organic and conventional produce are very similar, Shah said.

“There’s very limited evidence out there from scientific studies and whatnot that organic products (are) healthier or more nutritious than conventional products from an evidence-based standpoint,” Qamar said.

Qamar also attributed the rise in misinformation to marketing, since organic farming is more expensive than conventional production methods.

George agreed, also holding the media accountable for its role in spreading misinformation.

“I think we overcomplicate what we need to do to be healthy, and I think that that’s kind of where it all comes from, like fear and (misinformation) comes from (the) media,” George said. “I think marketing and all that, you know, it gets us.”

Despite the misconception that organic food is healthier than its nonorganic counterparts, all three agreed that at the end of the day, putting those nutrients into your body is ultimately more important than where the food comes from.

“If you’re shopping to improve your health, just eat more fruits and vegetables, period,” Shah said. “Americans are not eating enough vegetables to begin with.”