Hearing the word “poetry” might put some to sleep, but post-modern American prose isn’t anything like Emily Dickinson.

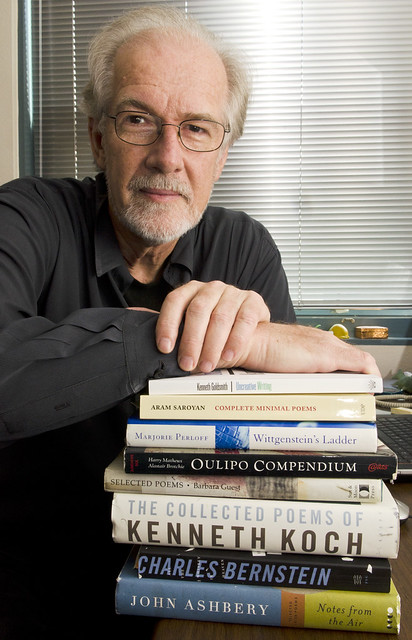

SF State’s creative writing professor Paul Hoover was selected by publishing giant W. W. Norton & Company to edit a post-modern American poetry anthology that will feature experimental forms of written word. The anthology will reflect the changes the poetry community has undergone since the movement’s start in the post-World War II era.

“It’s a movement toward conceptual poetry,” said Hoover, who edited a version of the post-modern American poetry anthology 17 years ago. “You could say the outrageous comes forward. It’s art because we say it’s art.”

Hoover described post-modern poetry to include poems with stanzas transcribed from distress calls to police stations, to death announcements aired during ball games and to flarf, which are poems crafted from search engine results.

He attributed the shift in artistic expression to technological advances, which spurred him to create a second version of the anthology.

“The media itself is part of the story,” Hoover said. “There’s a difference of temperament that occurred between the last edition and this one, and it’s a movement away from the romantic. The tone has changed.”

Ada Ha, a creative writing senior in Hoover’s American poetry class, described post-modern poetry’s boundless nature as being emblematic of creative writing students’ tendency to break the mold.

“They say creative writing students are the worst students possible because we can’t follow rules, were trained not to,” said Ha, who remembers being assigned flarf poems out of email spam. “It’s more free expression. It allows more room to speak your mind without being critiqued in a way.”

Hoover said the anthology will feature many local poets such as Michael Palmer, Kathleen Fraiser and Maxine Chernoff, the chair of SF State’s creative writing department.

“There are two major poetry towns in this country: New York and San Francisco,” Hoover said. “You could fall over and hit a poet in these towns.”

While anthologies have potential to promote a writer, one who will be featured in the new edition acknowledged the limiting nature of a definitive compilation.

Alumna Rae Armantrout described the conflicting reservations poets may have about being selected in such a work.

“Anthologies are funny things (because) they’re very powerful,” said Armantrout, who earned her master’s degree in creative writing in 1975. “So the selection that a particular editor will make will represent your work, and perhaps not in a way that you would have. After you’re dead and gone, (readers) may only see your work in an anthology.”

According to English Professor Bruce Avery, being chosen to compile a Norton collection is prestigious.

“It’s a huge honor. They are the dominant publisher in our field,” said Avery, who uses Norton textbooks in half of his classes. “They go through a long process before they settle on somebody. It means you’re the top in your field.”

Hoover expressed his self-ascribed duty to pay respect to the artists in his anthology, which he expects to be completed in three to four months.

“I’m glad I can be of service to the literature because I’ve followed it my whole career,” Hoover said. “I feel somewhat responsible for it, that it be treated well and that it receive notice.”