SF State has spent more than $600,000 on furniture and services from the California Prison Industry Authority in the past fiscal year from July 2014 to June 2015, according to university records.

The University has utilized services from CALPIA, a prison labor agency that assists inmates with occupational skills, for more than 15 years, according to Stephen Smith, SF State’s director of procurement.

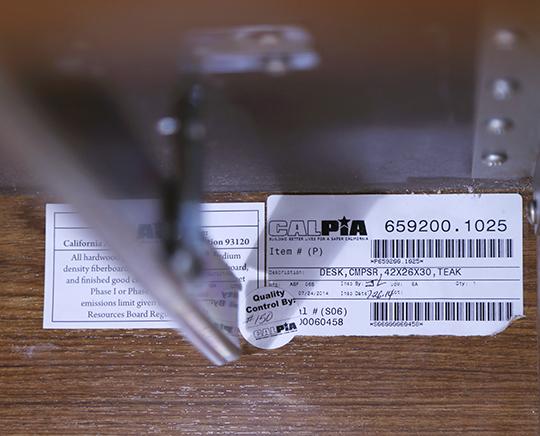

Residence halls are furnished by desks, chairs and beds assembled by inmates employed by the CALPIA. Underneath each piece of furniture made by CALPIA has a label with CALPIA’s logo.

CALPIA pays incarcerated workers between 35 to 95 cents per hour, which is taxed by as much as 50 percent, according to the agency’s website.

Jason Bell, the director of Project Rebound, an organization at SF State geared toward helping formerly incarcerated students earn their degrees, said he wished students knew that agencies like CALPIA are more focused on making money than helping inmates. Although the companies involved readily profit off inmate labor, they consider inmates unhireable after they are released from prison because of their criminal record, according to Bell.

“It sounds good while you’re in (prison), because it’s better than having nothing,” Bell said. “You’re good enough to work in custody; you can do a lot of good things that make you employable on the outside, but it doesn’t always transfer beyond the walls, and I hope students know that when (people use the term) for-profit (prison), it’s not for the profit of (the inmates).”

With nearly 7,000 prisoners employed in 22 California prisons under the California Department of Corrections, CALPIA operates within more than 50 service, manufacturing and agricultural industries, according to the agency’s website.

“The conditions are very similar to what these men and women will encounter when they are working on the outside,” said Michele Kane, the chief of CALPIA’s office of external affairs in an email. “We have factory, office and classroom settings.”

To assist with employment options after prison, CALPIA trains inmates to build a variety of furniture products including chairs, desks and beds and even offers training in computer programming, according to CALPIA’s website.

As the director of Project Rebound, Bell currently works with former inmates and said he spent most of his 20s behind bars.

“When I was housed in Solano prison, it was more like a factory setting,” Bell said. “They were making beds and tables. Folsom (prison) does license plates, but a lot of the furniture in the state agencies is from (CALPIA).”

The low labor costs and high profit margins ultimately benefit CALPIA but not the inmates, making the company money in an exploitative way, according to Bell.

“The goal is (reducing) recidivism,” said Roy Sorenson, the staff services manager of sales at CALPIA. “Offenders are 28 percent less likely to come back (to prison),” after participating in CALPIA’s program.

The recidivism rate has decreased by nearly 7 percent from 61 percent to 54.3 percent from 2008 to 2010, according to CDCR’s 2014 Outcome Evaluation Report.

“If the CALPIA program can give job training and work experience that translates into acquiring job skills that could get someone a job upon release then I believe there is a benefit there,” Jim Dudley, a criminal justice lecturer at SF State, said in an email.

Helping inmates obtain employment after prison has a greater benefit for society as a whole, Dudley said.

“Otherwise, we, the tax-paying public, run the risk of continuing financial support to those released, in some form or another,” Dudley said. “We may end up paying into welfare or other support or by way of being victims to continued criminal behavior.”

Prison industries are essentially free labor, according to senior international relations major Cynthia Morfin, who said she believes SF State utilizes CALPIA as a cost-saving measure.

“It’s really sad that SF State is willing to compromise its morals and the history it has of being so progressive,” Morfin said.

Joseph Miles, the office coordinator of Project Rebound, said he is completely against CALPIA.

“It’s simply slave labor, and the so-called skills taught aren’t useful under any circumstance or even applicable in today’s job market,” Miles said.

Resolving the issues with for-profit prisons entails establishing a system that empowers and successfully rehabilitates prisoners, Bell said.

“(Prison labor) is a state-wide problem that is bigger than just this school,” Bell said. “A large portion of the Rebound master plan has to do with taking the profit out of prisons and putting the power of reentry in the hands of formerly incarcerated people.”