California ranks highest in the U.S. for having the most organized hate groups, according to a recently released report.

The annual study, known as the “Intelligence Report,” was authored by the Southern Policy Law Center, which tracks hate groups. The number of hate groups rose nationally last year, and experts argue that much of the increase is due to space for bigotry created in the discourse during Donald Trump’s candidacy.

The SPLC only identified two hate groups in San Francisco: one is a white nationalist publisher by the name of Counter-Currents Publishing, and the other is the Loyal White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. Lecia Brooks, outreach director at the SPLC, said most of the White Knights’ activity had been confined to recruiting since they were a small group with declining membership. But Brooks does not want to minimize their presence.

The mere mention of the Klan would have a “chilling effect on people of color, especially black people,” Brooks said.

The report also named Identity Evropa, a white nationalist group that targeted SF State last October, as among those most active on college campuses. Nathan Damigo, who leads Identity Evropa, is a student at CSU Stanislaus in Turlock.

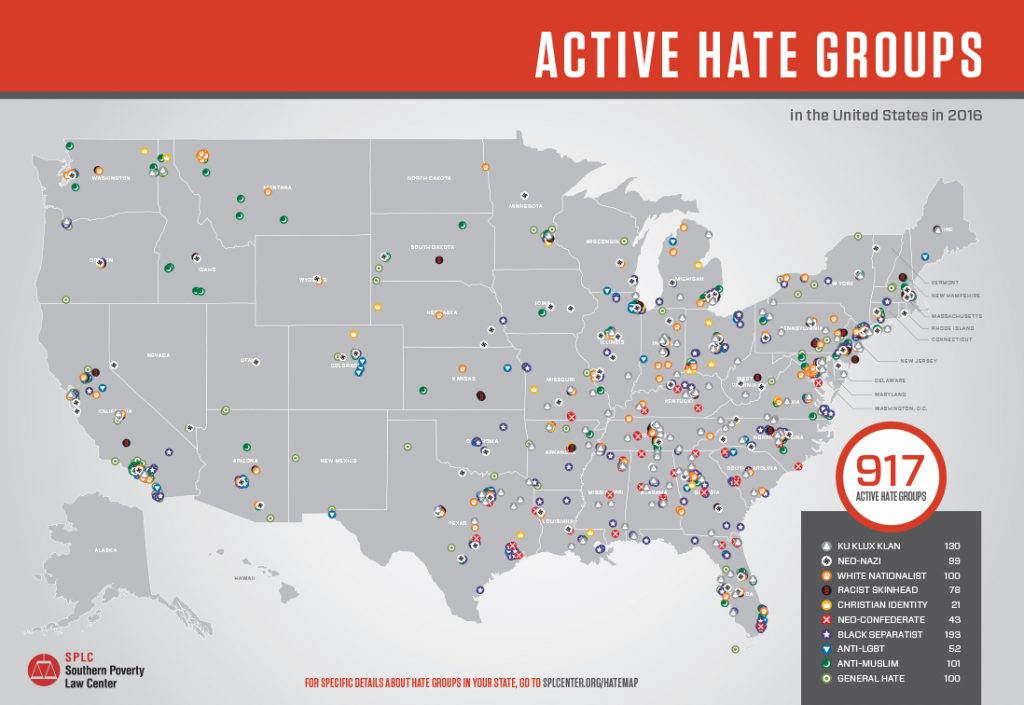

A total of 917 hate groups across the country represented an increase of 3 percent nationally in 2016, up from 892 total the year before. However, the incremental uptick in total hate groups masked the most dramatic shift. According to the report, anti-Muslim groups were up from 34 to 101, an increase of 197 percent.

Brooks noted other trends that were not immediately visible in the data sums. She pointed out that American Vanguard, a white nationalist group based in Huntington Beach, California, had moved from a solely online presence to a real-world presence with physical chapters.

Most of California’s 71 hate groups documented in the study were centered in urban areas, with the majority of those based in the greater Los Angeles and San Diego urban centers. This would seem to contradict conventional wisdom. Analysis in much of the popular media revolved around an urban-rural divide, claiming that rural voters were likelier to be more conservative than their urban counterparts.

Ali Kashani, an SF State political science and philosophy lecturer, said there was no doubt that a straight line could be drawn between increases in hate group numbers and the dialogue that came from the Trump administration. Kashani saw the rhetoric as “questioning the notion of politically correct language.”

As a result, Kashani said white supremacists and others no longer feared espousing such views in public.

“This was a shock to white, liberal people in Northern California. Minorities have a different experience with these things.”

Kashani said minorities such as himself had experienced the same kinds of disparaging language associated with the Trump campaign, pointing out that the real difference in Trump’s campaign was a lack of attempt to conceal the attitudes that produced hateful language.

“One has to consider that Trump is not the problem,” Kashani said. “He is an effect of the larger problem.”

That larger problem is what Kashani sees as the “neoliberal rationale for governing,” which is at its root economic.

Tad Isaacs, an SF State political science lecturer who specializes in social movements, agreed that an increased number of hate groups may have something to do with a surging right wing.

“I don’t think there is any doubt that the ascendance of the far right in the U.S. and internationally has made it more comfortable for those harboring white nationalist, white supremacist, anti-immigrant or racist views to express these views publicly,” Isaacs said in an email.

Isaacs believes much of the increase in the number of hate groups is a byproduct of the atomizing effect of the internet and other forms of mass media that affinity groups use for organizing rather than a “proliferation” of hate itself.

“The Klan and the White Citizens Councils of the mid-20th century might well have split into a number of different named groups if today’s communication technologies had been available to them, but their constituencies would have been largely the same,” Isaacs said.

Another explanation for California’s sizeable hate group population may be accounted for by looking at the metric used by the SPLC for qualifying and organization as a hate group. Brooks said organizations are included when and “if a group vilifies or demeans a group based on their immutable characteristics.”

This means many minority-based organizations, like the Nation of Islam, are included in the definition. Kashani disagreed with this approach, believing that a component of racism must include some ability to act upon it.

“In order to be racist in terms of actually practicing it, you have to have some power,” Kashani said.

Isaacs views the renewed openness with which racist views are now commonly expressed in the political discourse as a problem for the gains of the Civil Rights Movement. He believes an intolerance for hate speech was a net positive for people of color and may continue to be.

“The hope was that attitudes would follow behavior and that hate and racism itself would diminish among succeeding generations,” Isaacs said. “I believe that the hope has been realized to at least some extent.”

Tito • Mar 7, 2017 at 2:40 pm

Scary!