At the foot of San Francisco City Hall, “A Day Without Immigrants” marchers, activists and allies rallied around an unconventional symbol for immigrant worker rights: the paleta man.

Just before 3 p.m. at the May Day immigrant workers strike, a San Francisco park ranger doled out citations to two ice cream vendors, known as paleta men, for not having a vending permit.

The paleta men, Marcos and Ramiro Gutierrez Ortiz, were standing off to the side selling ice cream to children and participants listening to speakers.

Ralliers shouted “shame on you” as they broke off from the rally and crowded around the park ranger and the paleta men.

“We invited [the paleta men] to be here,” said Rafael Picazo, community monitor captain and San Francisco native. “We need relief in this heat. But just being here for our people, they get a ticket.”

Picazo, who helped organize the rally, assured the crowd that the tickets would be paid off for the paleta men and encouraged onlookers to buy ice cream to support Marcos and Ortiz, prompting the crowd chant, “Sí, se puede.”

Within minutes, Marcos sold out of ice cream and made his way home to the Mission District, while Ortiz lingered until the end of the rally.

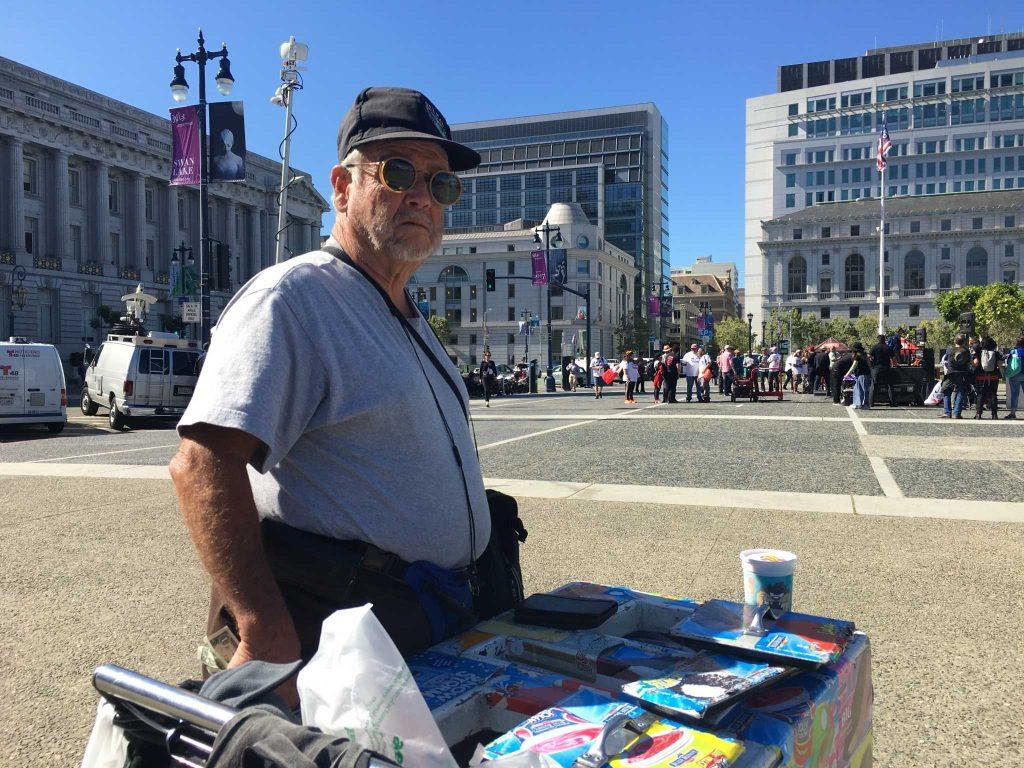

Paleta men and women, familiar faces in the Latinx community, have pushed their carts throughout the city, notably Dolores Park, on bright afternoons and linger in front of schools after schools let out.

“It’s the same thing as seeing a teacher,” said 17-year-old Anthony M., a senior at James Logan High School in Union City who declined to give his full name. “You see them working, and you learn the value of a dollar.”

Most paleta men and women are immigrants working to support themselves and their families. Many don’t have required permits to sell ice cream on the streets, making them easy targets.

“It’s like throwing out a fishnet,” said lead organizer Roberto Hernandez. “[Police] see what they can catch,” Hernandez continues. “It shows how alive racism is. Even in San Francisco.”

Hernandez, born and raised in San Francisco and a champion for immigrant worker rights, said the two men were racially targeted.

Ortiz, originally from Guadalajara, Mexico, carries his passport in a small, worn leather case in his cart in the event that police ask him for identification. Despite living in San Francisco for 27 years and selling ice cream for eight of them, Ortiz still treads lightly around authorities.

“We are the hardest working people,” said Hernandez. “We are the janitors, the field workers, the nannies. I don’t see anyone else scrubbing toilets.”

While Picazo shares the same sentiment, he doesn’t feel the need to differentiate between Americans and immigrants. “If they want to work, let them work. They’re Americans,” Picazo said.

SF State alumnus and film director Jason Zavaleta explained that the park rangers, not the officers from the San Francisco Police Department, are responsible for the tickets.

“[Rangers] have a choice,” Zavaleta said after speaking to one of the rangers on site. “It’s at their own discretion.”

Zavaleta, a member of the May 1st Coalition, noticed some rangers turned a blind eye to the paleta men but understands why others wouldn’t.

“If someone’s child got sick people [would] start asking why the park rangers didn’t do their job,” Zavaleta said.

As the rally came to a close, almost two hours after the incident, Picazo announced that his 16-year-old son, Michael Picazo, succeeded in convincing the park ranger manager to dismiss the tickets.

“We clean this town and we clean the city buildings,” Picazo said. “But we are not a dirty people.”