Duriel Meisner woke up with nothing to do on July 4, 2018. They showered, changed, and gathered their things to go hang themself on Mount Tamalpais.

For weeks, Meisner, a third-year art studio major, said they struggled with intense suicidal ideation, flipping between feeling fine and deciding to end their life.

They practiced tying knots and using belts to asphyxiate themself. During a party they used a friend’s toy gun to visualize shooting themself over and over. At one point, they took out their stepfather’s gun from the safe in their garage and a friend took it away.

“Holidays are hard for me,” Meisner said. “It was the most determined in my life I’d ever been to do it.”

At this point, Meisner had yet to be diagnosed with borderline personality disorder or BPD, and they did not yet identify as gender non-binary.

As they walked to their car to head to the mountain, Meisner turned around to check if they had forgotten anything.

“This thought had cut through all of it—‘Do you want to see any of this ever again?’ And I just really started breaking down,” they said.

Meisner’s roommate drove them to the hospital at UCSF, where they were kept for about a week on a 5150 hold, a temporary non-voluntary psychiatric commitment for those who are determined to be a danger to themselves or others.

Gender non-binary college students are most affected in suicidal ideation, stress, anxiety and depression, according to the California State University system’s 2018 Student Health, Wellness and Safety Report.

Students at SF State who are overwhelmingly anxious and depressed hoping to receive mental health services on campus may run into obstacles due to a limited number of healthcare professionals on campus.

Dwindling support

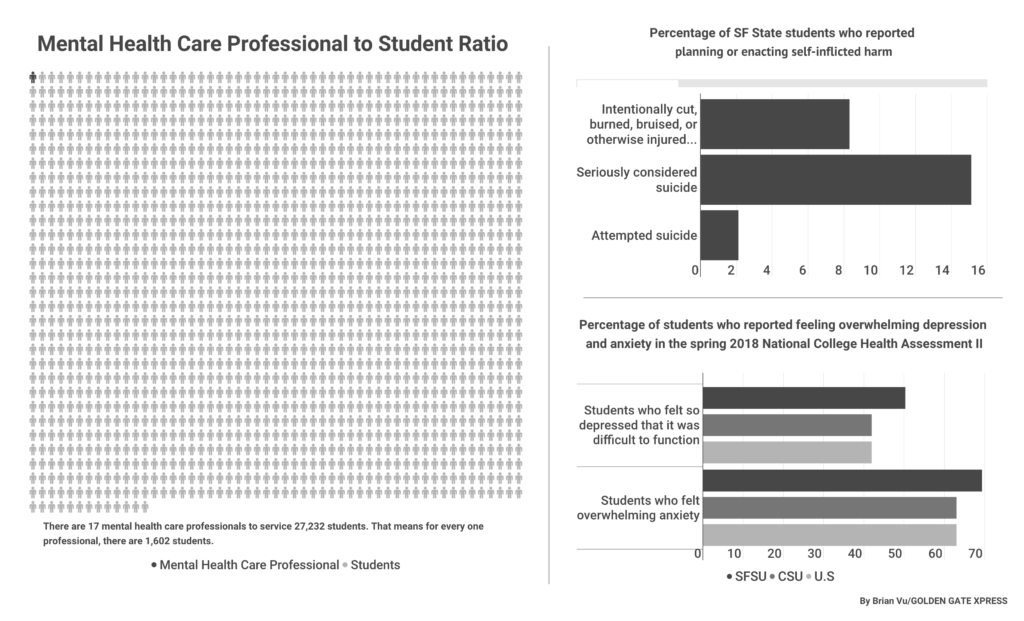

For the 27,273 students enrolled at SF State for the 2019 spring semester, there are 17 mental health care professionals, according to Associate Vice President of Student Affairs Gene Chelberg.

Chelberg is the head of Student Health Services, Counseling & Psychological Services or CAPS, Health Promotion and Wellness, the Disability Resource Center and the Children’s Campus.

SF State students reported more mental health issues than the national average among college campuses in the National College Health Association’s spring 2018 National College Health Assessment II.

Out of the SF State students surveyed, 69.4 percent struggle with overwhelming anxiety and 50.3 percent were so depressed they had difficulty functioning in the last 12 months.

On a national scale, 63.4 percent of students reported feeling overwhelming anxiety and 41.9 percent feeling so depressed that it was difficult to function.

The National Health Assessment is a voluntary study, and Chelberg said it is not 100 percent representative of the student body. Only one permanent psychiatrist who works part-time is employed by SF State in SHS, and two contracted psychiatrists work part-time, according to Chelberg.

Chelberg confirmed that the contracts of both temporary psychiatrists will terminate at the end of May. He said SHS is planning to hire a full-time psychiatrist to replace them.

Another option for students is to contact CAPS on campus. Chelberg said while there is one case manager and 12 counselors, Student Affairs is in the process of hiring a director who will also provide counseling to students.

Chelberg is the designee of the Vice President of Student Affairs, Luoluo Hong, in the Student Health Advisory Committee. SHAC members heard a presentation on the budget for CAPS and determined the mandatory Student Health Fee will be raised come 2020 to cover costs.

“What we know about the SHS fee is that the current revenue it generates does not cover the annual expenditures,” Chelburg said. “The good news is the SHS units have a reserve, so the balance that is not covered is being covered by the reserve.”

Funding mental health

Staff physician Kay Gamo said the lack of additional funding is concerning.

“In the 11 years I’ve been here, we’ve had some periods where we had zero psychiatrists,” Gamo said. “Certainly if a situation is more complicated and more challenging it’s absolutely essential that we have the ability to either have the student see the psychiatrist themselves or we can consult the psychiatrist.”

Chelberg said there is also one mental health case manager in SHS, a licensed social worker who helps students with insurance find more permanent solutions for therapists, psychologists or psychiatrists.

“I don’t think that’s enough, and we definitely know that because when the semester starts getting to midterms and finals we see that,” Gamo said. “Students are on waiting lists, they can’t get an appointment over at CAPS and they’re having waits to get in with the psychiatrist.”

Third-year English major Marc Lopez went to CAPS in October looking for counseling because he was feeling basic college anxiety and stress and was experiencing relationship issues.

At the time, the next available appointment was in December—two months away. Lopez determined that he was not in crisis and he could wait.

“I didn’t expect to be seen any time soon,” he said. “I think the counselors are really good at what they do. It’s just unfortunate that there’s just so many students here and so little counselors.”

He had two appointments and decided that he did not need to continue treatment, although he said he could see how some people needed access to routine counseling sessions.

“A lot of people move from their small towns to San Francisco, the city,” Lopez said. “That can be a really stressful change for them.”

CAPS Interim Director Cornel Morton retired from his position as Vice President of Student Affairs at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo before joining CAPS in September 2018.

“We have had situations where we had to ask students to delay seeing a counselor, if it’s not a crisis,” Morton said. “That’s important. If that student indicates they’re in crisis on the intake form, they’re seen right away.”

He said since CAPS is a short-term resource, students can see counselors as many as five times throughout the academic year. Some students will have more than five sessions and some will have fewer, and he said this depends on the individual student’s needs.

There is also the SAFE Place on campus, located in the same office as CAPS, which focuses on providing support to those who have experienced sexual violence.

“So far this semester we don’t have a waitlist, which is great,” Morton said. “We did have a long waitlist last semester, but again, it’s a function of episodic need on the part of the student community.”

Morton said that long waitlists can be an issue during midterms and finals, what he calls “academic crunches.”

Navigating transitions

Meisner said the services offered on campus were not sufficient to help them through the difficult transition into university life. They saw a therapist throughout high school but hadn’t received treatment for about a year before they heard about CAPS.

“The summer before my freshman year I went through a bad breakup, and it put me in a bad place,” they said. “I asked to see a counselor or a therapist and they were like, ‘OK yeah, our next available appointment is like six to seven weeks from now at 7 p.m.’”

In order to see a counselor right away, Meisner said they were referred to the Peggy H. Smith Clinic, located in room 117 of Burk Hall, where psychology graduate students provide counseling. These students are not licensed therapists. They complete clinical work under the supervision of CAPS counselors to receive their master’s degrees.

“It was really bad, honestly,” Meisner said.

“[But] they’re trying their best, and that’s cool.” Meisner ended up finding their own therapist in the city using their dad’s insurance and the website Psychologytoday.com. Since then, Meisner has seen two different therapists and a psychiatrist.

If a student needs long-term care and does not have insurance, the case managers at CAPS and SHS can help to connect them with no- or low-cost mental health care through non-profit organizations around the Bay Area.

Morton said the access to CAPS is “critically important” to students because the program works to address the “whole person.”

“We’re not only the intellectual being that shows up in a classroom and does academic work,” Morton said. “We’re also the emotive person or the spiritual person, we’re the feeling person.”

Meisner said they are doing better than last year without using the mental health services on campus.

“It’s been pretty good for the past couple of weeks,” they said. “I’ve been doing pretty well, made a lot of changes in my life and it’s been a lot easier to deal with the things that come up.”