The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict on Campus: Palestinian Student Experiences

This article is part of a series that seeks to explain and examine aspects of how issues around the Israeli-Palestinian conflict impact students, faculty, the university administration and academic programs. It is the work of over 80 interviews and numerous conversations that took place over a year. Taken together, these articles are meant to provide an overview of certain aspects of these tensions on SF State’s campus — and are not comprehensive.

Dec 1, 2020

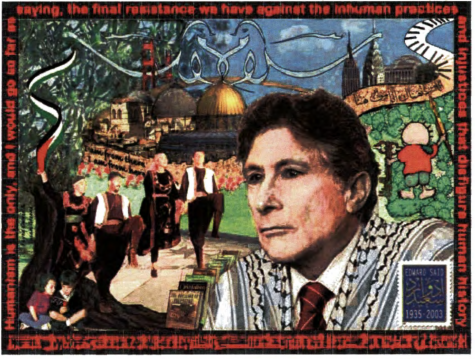

A mural of the late writer, academic and human rights activist Edward Said is featured above the entrance of the SF State bookstore. The mural was completed in 2007, after almost three years of objections and an eventual redesign, joining multiple murals on campus that display students’ backgrounds and leaders like Malcolm X and Cesar Chavez. (Paisley Trent / Golden Gate Xpress)

Hundreds of people walked past or under the mural portraying Edward Said while heading to class or entering the bookstore.

A second-year Palestinian student recalled looking at the Edward Said Mural almost everyday while walking around the SF State campus. They remembered the contemplative gaze of the Palestinian academic portrayed in front of a background weaving a depiction of SF State’s Malcolm X plaza with iconic landmarks from New York City, Jerusalem and San Francisco. Two cloud-like doves stand out in the bright blue sky, their intertwined figures spelling the word for “peace” in Arabic.

“Something that brings me a lot of joy as a Palestinian on campus is the mural,” the student said, speaking on the condition of anonymity. “Every time I see it, it just makes me happy that there’s something that’s a part of us that is visible on campus.”

The mural, which celebrates Palestinian heritage and commemorates the late writer, academic and human rights activist Said, was completed in 2007 — after almost three years of objections, leading to an eventual redesign. It joined multiple murals on campus that display students’ backgrounds and leaders such as Malcolm X and Cesar Chavez, illustrating the history and efforts of various social justice movements.

“The reason I chose SF State was more about, ‘I like it here’ and ‘I like that there’s like the one and only [General Union of Palestine Students] that’s left here,’” said another Palestinian student who spoke on the condition on anonymity. “I like that there’s a Palestinian mural. It kind of just makes it feel like I’m meant to be here.”

For other Palestinian students, SF State’s history of student activism and social justice was a reason to attend the university.

Although these students value aspects of the university that celebrate their identity, such as the mural of Said, this feeling of acceptance often fades when students hear about and experience attacks from pro-Israel organizations. Students have said that this sense of vulnerability has been exacerbated by a lack of support — and at times, vilification — from administrators.

For many students, the potential consequences of expressing weigh heavily against their freedom to express their identity and advocate for justice in and for Palestine.

When presented the initial draft of the mural by students, administration representative Richard Giardina suggested creating a policy to equally allot space to all student groups, saying that “problems could occur on campus” if other student groups opposed this mural. A subcommittee for the mural was approved in a 6-2 vote, with Giardina voting against it.

A week before the subcommittee planned to present its design to the main board, then-President Robert Corrigan wrote to the board, “The proposed mural is conflict-centered … Its spirit is less of a celebration than of challenge. In short, it is at odds with the most fundamental values to which San Francisco State University is committed.”

He asked the student board to send the design back to the arts committee rather than let it move forward. The board approved the design despite these concerns, and Corrigan placed a moratorium on all murals until the board created a new mural allocation process that the president’s cabinet approved of.

READ MORE about the different images and meanings of the Palestinian Cultural Mural featuring Edward Said on either Art Forces or Fayeq Oweis websites.

The initial design included Handala, a cartoon refugee child created by Palestinian artist Naji al-Ali, holding a pen in one hand and an old-fashioned key in the other. Corrigan wrote that these images were “explicitly offensive and identified with an international conflict, rather than celebratory of the Palestinian-American experience and culture.”

The key symbolizes the right of return for Palestinian refugees. Many Palestinian students in GUPS have been the grandchildren of those made refugees in the 1948 Nakba — the mass expulsion of Palestinians from their homes.

“I know plenty of Palestinians who keep their deeds to their homes and their keys, and that’s what that is also about — going back home,” said Noel Madbak, a 2019 SF State graduate. “But supposedly it was never our home, so I think it’s telling how threatening the key is. Because some people interpret the idea of us going home to mean we would kill them or go to war, but it shouldn’t have to be like that.”

However, some Jewish students and community members saw the symbols as representing hostility and political resistance to Israel, saying the symbols would send a chilling message to Jewish students and any supporters of Israel on campus. The right of return is seen as a threat to them because if all Palestinian refugees were to return to their old homes, it would change the demographics of Israel as a Jewish-majority state.

“In short, the Palestinian key is more than just a key, just as a conical hat on the top of a man dressed in white robes is more than just a hat,” wrote both the president and the executive director of the Jewish Community Relations Council in an op-ed for The Jewish Weekly News of Northern California.

In a dissertation on Israel’s Significance to American Jews, focusing on Bay Area experiences, Sarah Anne Minkin wrote how this view from the JCRC “collapses the expression of Palestinian identity with violence and race-hatred, closes off the possibility of viewing Palestinian self-expression as anything other than threatening to Jews.”

Because Corrigan didn’t approve the Palestinian mural until the images were removed, Palestinian students and allies felt the university blatantly sided with the JCRC, which praised Corrigan for his response. Palestinian students today remember him as someone who institutionalized the view that symbols representing Palestinian culture and political expression are threatening to Jewish students.

Upon hearing about this history of censorship from other students, Palestinian students who saw the mural as a reason they belonged at SF State said they felt at odds with the campus and the role of the administration in supporting social justice.

“It’s mixed emotions for me,” Madbak said. “I’m happy that we have a Palestinian mural. I’m proud of all the people that came before me that were able to make that happen. But it also makes me very sad that we couldn’t have things like the key on our mural that symbolizes our right to return to our homeland because that was too controversial.”

Madbak first joined GUPS in 2016, after SF State student organizations protested SF Hillel’s invitation of then-Jerusalem Mayor Nir Barkat to speak on campus. She felt the administration’s allowance of someone Palestinian students and others saw as threatening contradicted the university’s mission statement of social justice. GUPS student leaders found out about Barkat’s scheduled appearance at the last minute and came together with other student organizations to protest.

The university received criticism from Jewish faculty, students and community members and organizations over how it handled the protest and how members of the university police and administration failed to stop Jewish students and Barkat from being yelled over by protesting students. Dozens of emails, obtained through a public record request by the Lawfare Project, asked then-President Leslie Wong to investigate and punish the two Palestinian students who led the chants. Administrators threatened the students with expulsion and disciplinary procedures; however, a third-party investigation paid for by the university found administrators at fault rather than the students.

The two female Palestinian students involved in leading the chants were followed on campus and received rape and death threats, along with calls for their employment termination. An online blacklist compiled their photos, workplaces and social media, while others publicly shared their personal information.

Though Palestinian students have described experiencing a continual lack of support by the university administration in the midst of harassment from groups outside SF State, they have found continuous support from student groups on campus. In particular, they attributed members of historical campus organizations, such as the Student Kouncil of Intertribal Nations, whose members suggested and encouraged GUPS to propose a mural in 2005.

At an April 9, 2019 rally, the League of Filipino Students led a call and response. “I said ‘Rise up, rise up, rise up.’ Rise up, rise up, rise up. I said, ‘Rise up, my people rise up.’” Later, students led chants of, “From Palestine to the Philippines, stop the U.S. war machine.”

Many students emphasized that GUPS has given them a sense of community and joy, but their involvement with the organization is still riddled with double standards, accusations of antisemitism and concerns about potential retaliation for their beliefs and actions. These concerns have been persistent and haunting, especially considering the methods used by organizations such as the David Horowitz Freedom Center — known to plaster college campuses with posters listing the names of professors and students they claim have ties to terrorist organizations.

Palestinian students and a Palestinian professor at SF State have received Islamophobic death threats and hate mail.

Islamophobia often targets Palestinian students and supporters; however, Palestinian, Arab and Muslim identities are not synonymous. Not all Palestinians, Arabs or Muslims have the same viewpoint, politics or understanding of Palestinian identity or the issues around the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Nationally, students involved in Palestinian activism say they fear creating a social media presence, being quoted in newspapers or showing up at protests that could have them end up on a website that catalogs people as antisemitic.

Canary Mission is one website well-known by students involved in Palestinian-related activism. Its mission statement claims it focuses on documenting antisemitic individuals and organizations on North American college campuses that promote hatred of Israel, Jews and the U.S. This may include anyone who supports the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions Movement or disrupts Jewish or pro-Israel speakers.

Canary Mission’s database consists primarily of Arab and Muslim students and professors, though there are also Jewish students, non-Arab or non-Muslim academics and activists, as well as white supremacists. The profiles are also updated — some created in 2016 were updated in March and include a full range of social media information.

“I’ve always been hesitant to participate in anything public with GUPS that’s open to the rest of campus,” said a student in GUPS who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “I’m worried that I might end up on Canary Mission … I was always nervous about being singled out or recorded or someone using my speech or something I do against me. Especially on campus.”

Students say the blacklist villainies those advocating for justice in and for Palestine. It has instilled fear in students for their safety. Students are aware it could also affect their future employment or educational pursuits. Still, some refuse to suppress their beliefs.

“It just makes me want to work harder,” said Sabreen, the current president of GUPS. “What I’m standing up for is right and just, and [Canary Mission is] not going to stop me from continuing my work for the liberation of Palestine … If somebody doesn’t want to hire me because of my beliefs, then like, fuck it.”

According to tax documents obtained by The Forward, the San Francisco Jewish Community Federation donated $100,000 to Canary Mission through a supporting foundation in 2016. The JCF and its Endowment Fund manages $1.6 billion in total assets and donates to many progressive institutions around the world.

The JCF responded that it has reviewed its policies and guidelines and that it will not support Canary Mission in the future. However, in the past, the JCF and a supporting foundation also gave to the David Horowitz Freedom Center and other right-wing or anti-Palestinian organizations, and the JCF has continued to donate to anti-Muslim hate groups and media sites such as the Clarion Project and Middle East Forum.

The impact of Canary Mission goes beyond concerns for job and graduate school prospects. The Israeli Defense Forces use Canary Mission when questioning and screening people coming into Israel or the West Bank. For Palestinian students with family there, the potential to be denied entry when visiting family has additional consequences.

“It’s also scary, because even me doing this [interview] and me being involved, it could potentially impact me ever going back to Palestine,” said a student with family in Palestine who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “Like, this really affects our lives in ways it doesn’t affect people from Hillel’s lives. For them, it doesn’t affect them if they want to go back to the Middle East.”

In March 2017, Israel began denying entry visas to foreign nationals who advocate for any form of a boycott against Israel or the West Bank settlements. The country has barred Palestinian and Jewish activists and students from entering as a result. This law was used to initially ban entry for Congresswomen Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib in 2019.

That same year, a contentious definition of antisemitism was enshrined in an executive order by President Donald Trump, causing concern among Palestinian students and public university administrators about potential legal action against them or loss of funding.

Citing antisemitic harassment on college campuses, the executive order stated that departments and agencies enforcing Title VI — which prohibits discrimination based on race, national origin or color in programs receiving federal funds — must consider this working definition of antisemitism. In particular, this includes contemporary examples of antisemitism such as denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination by claiming Israel is a racist endeavor.

Jared Kushner wrote in a New York Times op-ed, “[This definition] makes clear what our administration has stated publicly and on the record: Anti-Zionism is anti-Semitism.”

“This executive order is not about protecting Jewish students or to actually address anti-Semitism like the growing amount of white supremacist groups on university who continue to organize with no repercussions,” wrote GUPS in a Dec. 11 statement. “This is about silencing Palestinian student organizers, faculty, and any ally that speaks up for the rights of Palestinians and to all who push for BDS on their campuses. It is clear what this executive order is, to silence any criticism of Israel and to silence the growing powerful voice Palestinian student organizers.”

The lead drafter of the definition of antisemitism used in the order, Kenneth Stern, has spoken out against Trump’s executive order. He expressed concern that it will have a “chilling effect” on campus free speech, as administrators worry about being sued, and the government gets to define how Zionism fits into Jewish identity — something he acknowledged is debated within the Jewish community.

Earlier this month, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo made an unprecedented visit to an Israeli settlement in the West Bank. Pompeo said the Trump administration plans to label all products from the settlements — illegal under international law — as products of Israel. He also announced the usage of the working definition of antisemitism in labeling the BDS movement as antisemitic and “a cancer,” promising to cut government funding to organizations that support it.

Amid the threats of blacklists and surveillance, these government actions have only heightened concerns by groups of students that their freedom of speech is restricted at SF State — fears that students said the college administration has left unaddressed.

“I think most students don’t realize how serious it actually is … like, ‘We live in San Francisco, this is America, you have freedom of speech,’ but actually no it’s not like that,” said Palestinian student, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “Coming here, I realized it’s not that simple.”

Excerpts from “Palestinians say their free speech is endangered,” written by Norma Shiheiber Sayage in the Golden Gater, published on March 10, 1987.