A fighety screen twitched from mundane advertisements to a play. Two characters, meshed together via their Zoom backgrounds, enter frame into the first Zoom play of the school year.

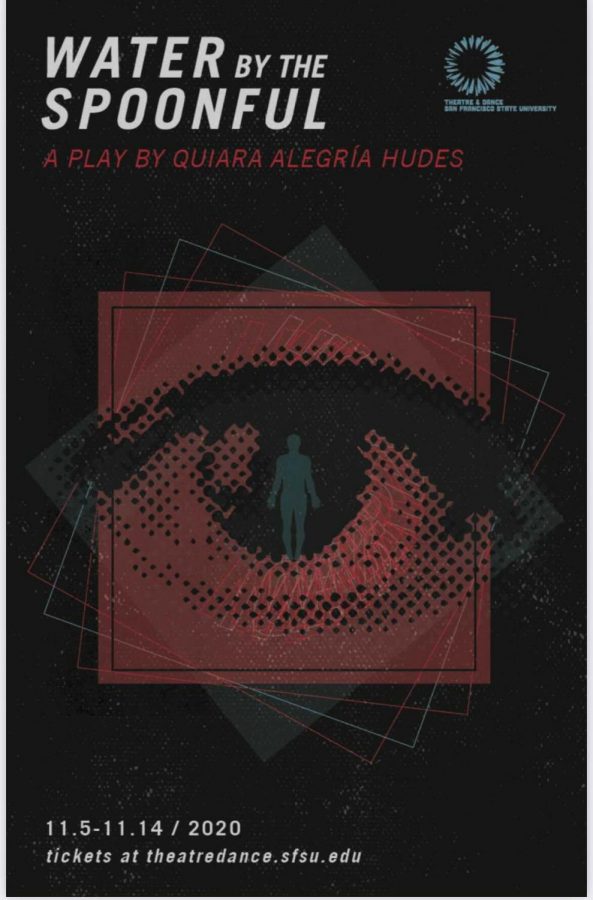

The SF State theater department had to host their Fall play via Zoom this semester. “Water by the Spoonful,” by Quiara Alegria Hudes, was hosted weekends of the 5th and 14th of November, making it available for anyone with Zoom access. Due to pandemic related restrictions, this was the theater department’s first play to be produced and performed entirely through online video chat.

Rhonnie Washington, director of the production, said initially the play was intended for the spring semester but felt the move to online was a smart one.

“The department chair figured that it might be a good way to go at it. This might be a good selection for the fall because of the whole online aspect of it, so it was moved from spring to the fall,” said Washington.

The design process for the show started in February but was halted and put on prolonged hiatus with the onset of the pandemic.

“We were thinking that we were going to present it on stage, in theater we didn’t find out until April we were not going to be in-person in the fall,” said Washington, “we somehow had to adjust the design so that they can function on a online world other than a three dimensional world.”

The production’s actors had to audition for their roles virtually via Zoom, with Washington deciding. Washington said he felt that the cast decisions had come out great but also commented on the fact that the selection process took longer than usual as they couldn’t find the center characters of character Chutes and Ladders, who are supposed to be a 55-year-old African American man. “I said you know if worst comes to worst Chutes and ladders is a 55-years-old African American man I can do that,” said Washington.

Rehearsals for the show took up to eight weeks, Monday through Friday. Washington explained that there was no conflict with scheduling which made rehearsals facile r.

“It was a great kind of process because nobody really had conflicts. When you’re rehearsing in the real world often there are conflicts,” Washington said.

During rehearsals and during performance, there were technical difficulties such asWIFI issues. Jasmine Murray, the stage manager, would put up, “Stand-by,” sign every time there was an WIFI issue, and a pre-recorded performance was put onto the Zoom screens, so actors are able to get their WIFI controlled again.

“We recorded rehearsal every night, if there was a rehearsal that we liked better than the last recording that became the go-to recording,” said Washington. “So when we had problems, we went to the recording.”

When the recordings of previous rehearsals were put up, actors were told to stand-by for the next scene.

Murray, who stated this was their first time working as a stage manager virtually, found it difficult not being in person.

“It was a lot harder than being in person, just because of all the new software that I had to learn how to use, and not being able to handle problems in person and having to go through email for everything,” said Murray.

To communicate during show times, Murray will use a video conference app called Discord, to connect with the designers, and communicate with the actors through OBS Ninja.

In regards to designing the play Washington stated that the design team managed to make a design that allowed every character fit into scenes. Each scene had a background that would merge each actor’s individual Zoom box into a single cohesive backdrop

Ray Oppenheimer, who worked as the production’s Zoom engineer and lecturer, helped actors with placements during the play. Oppenheimer conducted the engineering process through his at-home computer during production.

“Zoom really doesn’t do well with performance, so being on zoom there’s a couple of fundamental things that are different,” said Oppenheimer. “You can’t see the audience there. You can start to have an argument over whether or not what value is there from being live to recorded.

Oppenheimer explained that. “In zoom if someone’s internet goes down then you can’t do a performance,” he said. Before showing, zoom engineering took place two weeks before showtime, according to Oppenheimer.

Many third-party tools were used to work with audio, such as OBS Ninja, to prioritize the sounds of each character.

“One of the things you might notice about zoom is that whoever’s talking loudest wins, so we had to use a bunch of third party tools,” explained Oppenheimer, “we injected [OBS] into Zoom, tricking Zoom into thinking it was a webcam feed as a way to be able to hack sounds or performers talk over each other and not have zoom prioritize one audio to other.”

To get all the performers to have green screens, OBS Ninja was used again to arrange the backgrounds for each actor.

“There was a lot of tweaking and it took a lot of time to figure out, the thing that I struggled with the most was to keep peoples internet stable enough,” Oppenheimer said.

Oppenheimer went on to comment on the fact the the whole ordeal was somewhat new for everyone involved, new and emerging at every stage of the production.

“We have a whole lot of creative people whose primary art form has sort of been stolen from them based on covid,” Oppenheimer said. “We’re seeing the emergence of a new art form that’s sort of a virtual performance art form.”