The club, founded during the Fall 2019 semester, has a reach that extends beyond the physical and figurative boundaries of campus

Oct 7, 2021

When Seretse Njemanze and Eric Webb met in an introductory film class at SF State, they bonded over a shared problem: a glaring need for Black representation within the cinema department’s student body and faculty.

For the Fall 2021 semester, the School of Cinema has 22 professors. Out of those professors, only one of them is Black.

“I just happened to notice that [Seretse] was one of the few Black people that were in there that was saying anything of content,” said Webb, referring to the moment that the pair met.

The recognition of the need for Black representation led the pair, both of whom hail from the East Bay, to create the Black Film Club during the Fall 2019 semester. Webb said that they wanted to create a connection between their film colleagues from the East Bay and their newfound film connections at SF State. Now, he says, the rest is history.

The Black Film Club’s goals, according to their description within the School of Cinema’s clubs and groups page, are to expand the visibility of Black films and filmmakers; highlight Black contributions to cinema; provide a support system for student projects; aid real-world clients and organizations who have shown support for Black upliftment; and to give students opportunities within film production services, both paid and unpaid.

One of the primary ways that the Black Film Club differs from an average campus club is that its reach extends further than the campus itself. According to Njemanze, the club has members from South Africa, Louisiana and Florida among other locales outside of SF State – not all of them are students of the university – because the club has its sights set on more than just campus-related activities.

While a lot of the club’s work has to do with on-campus activities, such as weekly meetings and workshops, much of the club’s effectiveness lies in networking.

The club has two sides that belong to the same coin: one side is the campus-based Black Film Club, and the other is Black Film Connect. Take the club’s Instagram page as an example; Njemanze said that while one would assume the handle would be “@blackfilmclub,” the page is actually named “@blackfilmconnect.” Njemanze cited the reason for this difference as being that the club uses the page to mostly emphasize networking for contract work, a bulk of what they do outside of campus.

“Film is not a degree where you can network on campus but not make films, or you can network on campus but not gigs,” Njemanze said. “You need to be doing it while you’re in school, and that’s literally anybody — doesn’t matter what color you are.”

Events and works that the club has done include film festivals, music videos, short films, in-house film productions, live shows, open mic sessions and live streams of club-produced films. One of the club’s biggest contributions, however, is giving some club members valuable experience working on a film production.

This is done through the Black Film Club’s job board. According to Njemanze, members of the club have access to the board, and it is typically updated daily, providing its members with paid and unpaid internships, gigs and general opportunities with hands-on work in cinema.

The Black Film Club had the bulk of its operations happen during the COVID-19 pandemic. While a lot of the club’s events and in-person exhibitions have adhered to social distancing guidelines, one of the pandemic’s biggest effects on the club lay within its weekly meetings. Once in-person, these meetings now occur virtually.

COVID-19 has also changed the dynamic of the club’s on-set workflow. Njemanze said that, ironically, their first film production during the pandemic happened to be one of their biggest. That set included 30 members cast and crew, and had to be filmed outdoors. When filming moved to interiors, Njemanze said, that number arbitrarily changed, but hovered around 10 or so people.

The bounds on cast and crew numbers were big limitations at the outset of the pandemic, Njemanze said, but one other limitation that stemmed from the early-COVID quarantine was boredom.

“What ended up happening is a lot of people had a lot of time on their hands,” Njemanze said. “We were looking to create, still, because the pandemic was already pretty boring, to be frank.”

Through this boredom, however, the club was able to create an “ultra low-budget” music video project that connected them to current members of the club from South Africa.

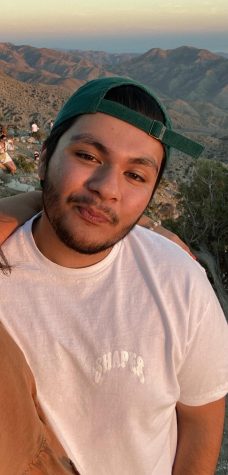

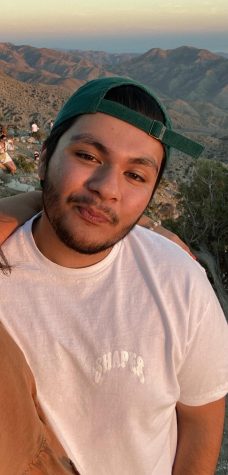

Thembi Nkosi, who was appointed president of the Black Film Club this semester, spoke about her vision for the club moving forward.

“I do see the club returning for in-person meetings, and I also hope for the club to be more involved with collaborating with other film organizations,” Nkosi said. “I think for the most part, that’s why people join film clubs, because sometimes the courses don’t accommodate for wanting some experience.”

While the Black Film Club has made an impact in and around their community, the club is operating in a time of flux in the industry. Over a year removed from a summer signified by Black Lives Matter protests in the wake of George Floyd’s killing, “Black content is in,” as Njemanze puts it. Although this may be true to a degree, the strife behind the Black film movement is the institutionalized problem hiding in plain sight under it.

“For the most part, I do feel like Hollywood kind of glosses over racial issues and content, and they don’t attack it head-on,” Nkosi said. One example she used is the 2018 film “Green Book,” which, despite an Oscar win for best picture, faced criticism for employing the “white savior” narrative trope.

The white savior trope in cinema usually consists of a white character who rescues a person of color from their problems, suggesting that the person of color can’t save themselves from said problems without the white character’s help.

She additionally mentions that acclaimed Black filmmaker Spike Lee even had trouble pushing his films due to how raw and direct they were in regards to addressing racial issues.

“It’s important to just make your movie, put it out there instead of waiting for permission to do it,” Nkosi said, “because when you wait for permission, then I don’t think it’s gonna manifest the way you want it to … I think that’s just it: make your movie, show it, express it.”

Nkosi also alluded to the aspect of gatekeeping within the film industry — how high-level film officials who make executive decisions often aren’t people of color — a point Njemanze supported.

“At the end of the day, there’s still gatekeepers,” Njemanze said. “They still pick which stories they wanna hear, they still pick what stories get made by them, and that’s why I think it’s really important to make your own stories.”

Njemanze also said that this uphill battle is one of the biggest influences on his work, and one of the main reasons he helped create the club.

According to a UCLA report published this past April on the subject of Hollywood diversity, only 2.5 out of every 10 filmmakers are people of color. The same report states that 2.6 out of every 10 film writers are people of color. For lead actors in film, the report says that 4 out of every 10 are people of color, a smaller yet significant difference. For an industry that suggests “Black content is in,” this is a glaringly large disparity.

Rafael Flores, a lecturer in the School of Cinema and the former faculty adviser for the Black Film Club, said that this disparity exists within a multitude of sectionalities, but applauds the club for the work they’ve done up to this point. He hopes that one day, “we can recognize the people that have been making sacrifices to do this work.”

“It’s so easy as a professor to kind of just stay in your ivory tower, and not really be engaged in the community,” Flores said, “but I think that academia has a responsibility to engage folks in the community.”

Flores held the position of faculty adviser for the club until this semester. He continually praised the Black Film Club, and said that he sees the club as an inspiration to himself, and to other potential clubs that are centered on underrepresented groups, particularly within the film industry.

“I wish that other groups would do the same. I tell that to a lot of my Latino students — I say, ‘Why aren’t you guys doing this?’ Why aren’t Asian students doing this? Why aren’t gay students doing this? All of the folks that need to improve their representation,’” Flores said, “I think there should be these types of clubs on every campus.”