Fifty-three years later, Third World Liberation Front strikers reflect on protesting on campus

Mar 20, 2022

Fifty-three years ago, the Third World Liberation Front strike, the longest student strike in U.S. history, came to an end. The strikes began five months prior on Nov. 6, 1968 at SF State.

The Third World Liberation Front strike — formed by the Black Student Union and other ethnic student groups — started in response to administrators revealing student academic standing to the Selective Service System and inequity on campus.

In 1968, only 4% of SF State’s population were students of color, yet they made up 70% of the students in the San Francisco Unified School District, according to the BSU’s list of demands.

Students a part of the strike also urged the school to retain suspended professors of color and establish colleges of ethnic studies. They risked violence toward them, assault and arrest to attain these demands.

“You’re stepping into some very dangerous, threatening situations and that oftentimes involve confrontations with the police at various various levels, whether it happened individually or in small groups,” said Roger Alvarado, Latino and Irish spokesperson for the Third World Liberation Front.

SF State English professor and Black Panther education Minister George Mason Murray was fired from his position, which became the catalyst to the formation of the strike. Students loved Murray, but he wasn’t tolerated by campus officials due to his anti-Vietnam war stance.

The BSU and the larger Third World Liberation Front went on strike together during the five months after they had collaborated for years; the Third World Liberation Front demanded retention of professors like Juan Martinez and Nathan Hare who taught a third world curriculum.

The BSU and the Third World Liberation Front demands were similar. Both groups wanted Murray to be reinstated to his role at SF State. The BSU demanded that all Black students who wanted to go to SF State be admitted, while the Third World Liberation Front demanded more people of color be admitted.

Sharon Jones, a Black Africana studies professor, was a freshman at SF State when the protests began in 1968. Jones was already a part of the Black Student Union in high school and was recruited to attend SF State by the organization.

On the first day of the strike she along with other protestors went from classroom to classroom to let people know the campus was closed, because they wanted to bring attention to their cause and demands.

“It was a feeling of uncertainty, it was quite scary at the time. I remember that was the first time I think I’ve ever witnessed police on horseback, tact squads, it was a lot going on,” Jones said.

A major obstacle student strikers faced was the increased police presence at SF State. Jones recalled a moment during the protests where she and around 400 others were arrested. She was even hit in her stomach with a billy club by a police officer. The protestors’ organization bailed her out of jail hours later.

“I came from a very religious household,” Jones said. “My mother, you know, we prayed about it. We didn’t strike about anything we prayed. So it was like by the time I got home that my mother had no idea that I had been to jail,” Jones said.

Alvarado said that university students past and present have been at the forefront of presenting unaddressed issues, although he feels that these changes aren’t sustainable.

“You search out, you get some change, but because the structure stays the same, it just eventually does co-opt to some extent, the things that you’ve achieved,” Alvarado said.

Alvarado said that graduate students worked after the strike to make their demands a reality. One of the settlements created after the strike was that a committee of ethnically diverse faculty of staff and students must be created to address inequity and racism at SF State.

College of Ethnic Studies Dean Amy Sueyoshi compared the Third World Liberation Front strikes to a hunger strike that occurred in 2016 in the College of Ethnic Studies. Although the 2016 protests were different due to established time, place and manner rules.

These rules place precedence on planned events from 7 a.m. to 10 p.m,. Monday through Friday, scheduled through the Dean of Students office and the Enterprise Risk Management office; rather than spontaneous protests and events with heavy sound usage. These types of events must be done when class is not in session between 12pm-2pm.

“I think that what’s very different now, which wasn’t the case in 1968, is that the administration is largely supportive of the same values as students,” Sueyoshi said.

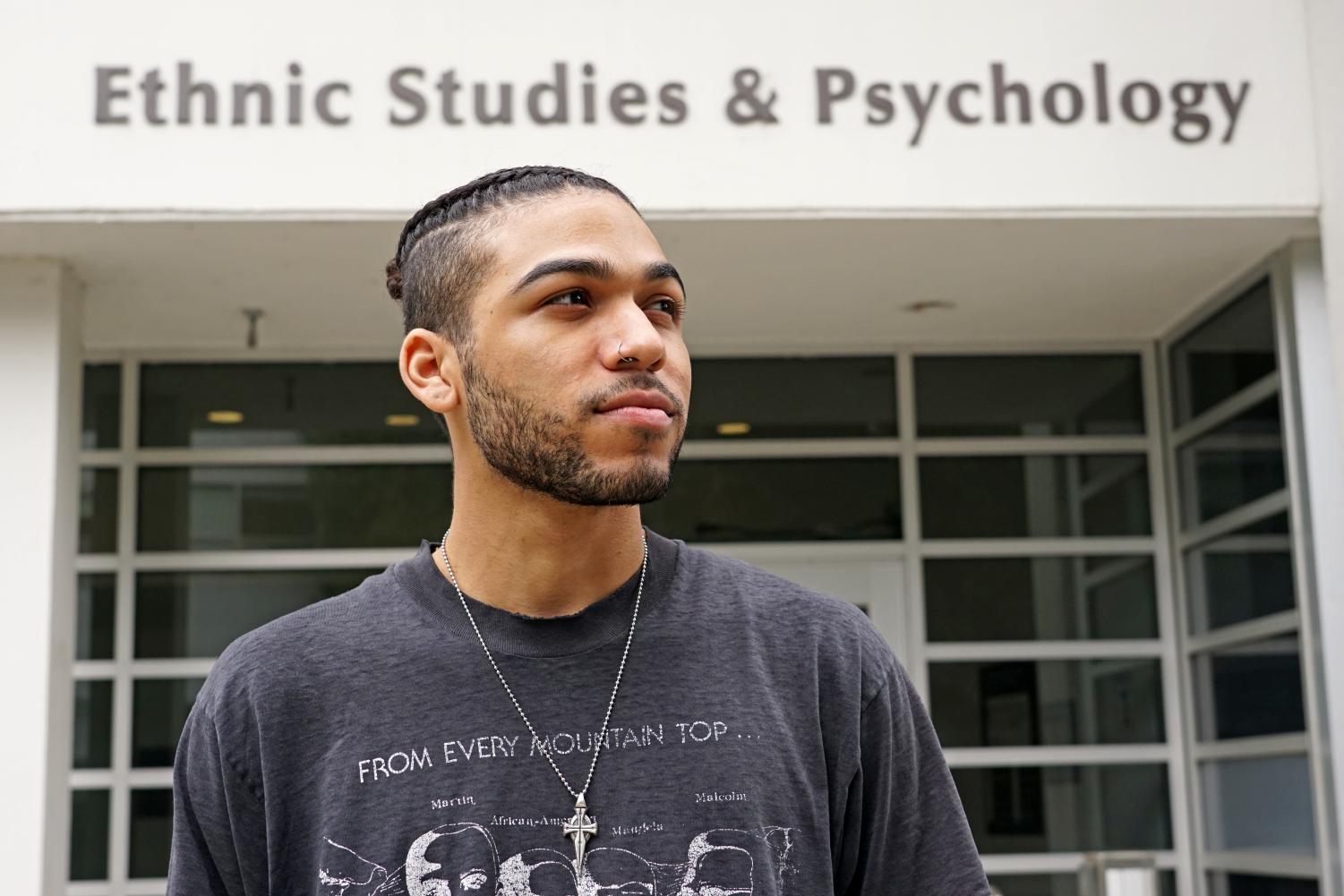

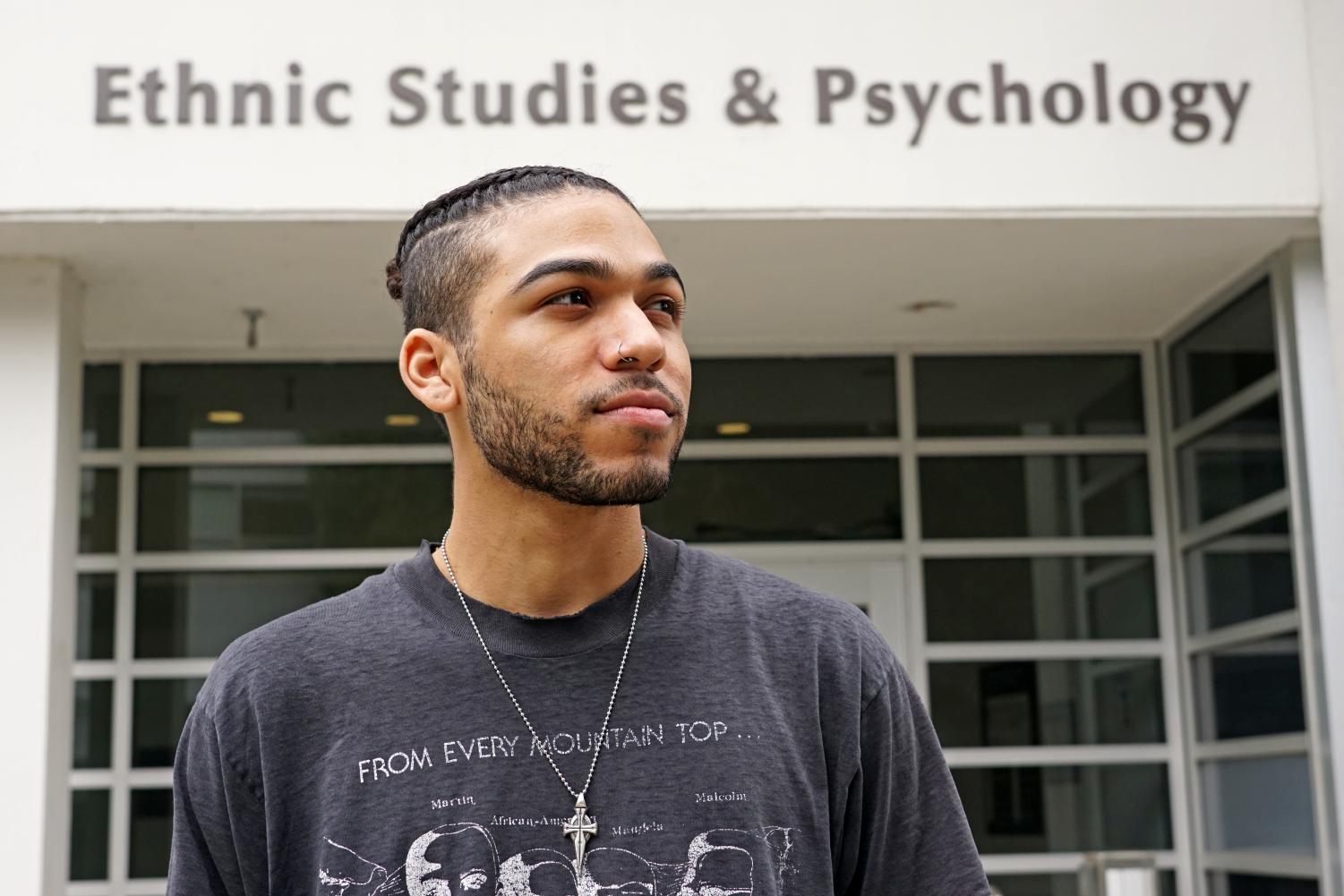

Fourth year international relations major and BSU vice president of external affairs Lee Lockhart disagreed, expressing that it’s tougher for students to protest on campus due to these rules in place.

“I don’t think this is specific to SF State,” Lockhart said. “I think the educational institution, the university system as a whole tends to favor outside protesters over students because students are a sensitive demographic.”

Jones recalled that in the years after the strikes ended, many strikers were blackballed from their respective industries, including the chairman of the BSU at the time Benny Stewart who was studying to be a lawyer. He went on to be involved in the economic development in Marin City.

After their five month strike, the Third World Liberation front and the BSU were able to create the first college of ethnic studies and a Black studies department, which continues to be celebrated decades later.

“You know, there was name calling, and a couple of fights and whatever but we were there to finish [and] get to wherever we were going,” Alvarado said.