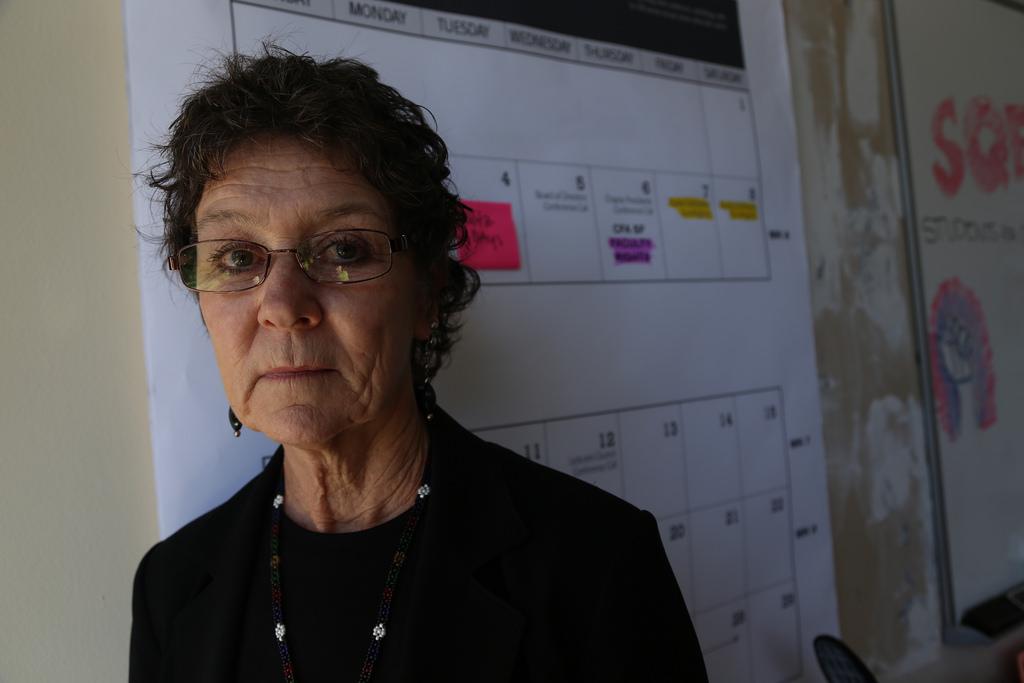

Sheila Tully, SF State’s California Faculty Association chapter president, poses in her office in HSS 331 at SF State Tuesday, March 18. Photo by Rachel Aston / Xpress

Sheila Tully, SF State’s California Faculty Association chapter president, poses in her office in HSS 331 at SF State Tuesday, March 18. Photo by Rachel Aston / Xpress

Anthropology Lecturer Sheila Tully took what is known as the “academic path.” She obtained bachelor’s, master’s and doctorate degrees in areas of study that inspired her, and took a part-time teaching position at SF State.

Tully thought that if she worked hard she could live comfortably in San Francisco, and she did for 28 years on an income never exceeding $40,000 annually – until two years ago when the rent-controlled building she lived in with her family was sold.

“Getting evicted was an emotionally hideous experience,” said Tully. “We raised our daughter there, we knew all our neighbors, we used to have pizza night on Fridays with all the kids in the neighborhood. And then it was just like ‘sorry, you don’t have money, you have to go.’”

After a disheartening process of competing for affordable apartments, often times with her own students, Tully and her husband settled on a flat renting for $900 more a month than what they were paying. As they struggle to make ends meet, Tully puts her faith in the CSU system to consistently provide her with enough courses to teach. If it proves unreliable, as it has in the past, she and her husband may have to leave San Francisco altogether.

Tully’s circumstances are not uncommon among contingent faculty. Lecturers, the accepted term for part-time professors hired on a contractual basis, are often constrained to frugal lifestyles similar to the college students they teach.

In a national survey recently released by the House of Representatives, lecturers frequently reported living with multiple roommates, commuting long distances and supplementing their income by waiting tables or working in retail. Last Fall, Al Jazeera highlighted an SF State lecturer with a Ph.D. and stellar student evaluations whose financial woes drove him to reside in his parents’ basement.

Lecturers’ troubles only begin with their low salary – part-time adjuncts in the US earn between $20,000 and $25,000 per year, NPR reports. The position often provides no job security, no promise of a substantial pay increase and few opportunities for full-time or tenure-track positions. SF State has more part-time lecturers than ever before, as more than half of the university’s faculty is off the tenure track, according to SF State data.

College was not always like this. In 1975, part-time adjunct faculty made up only 24 percent of the national two- and four-year college instructional staff, according to a report by the House of Representatives. Now, contingent faculty make up 75 percent of the nation’s academic workforce.

“The idea of lecturers has evolved,” said history lecturer Mark Sigmon. “It used to be an emergency fill-in-the-gap thing, but then as the budget tightened, the administration started seeing the financial advantages of hiring lecturers.”

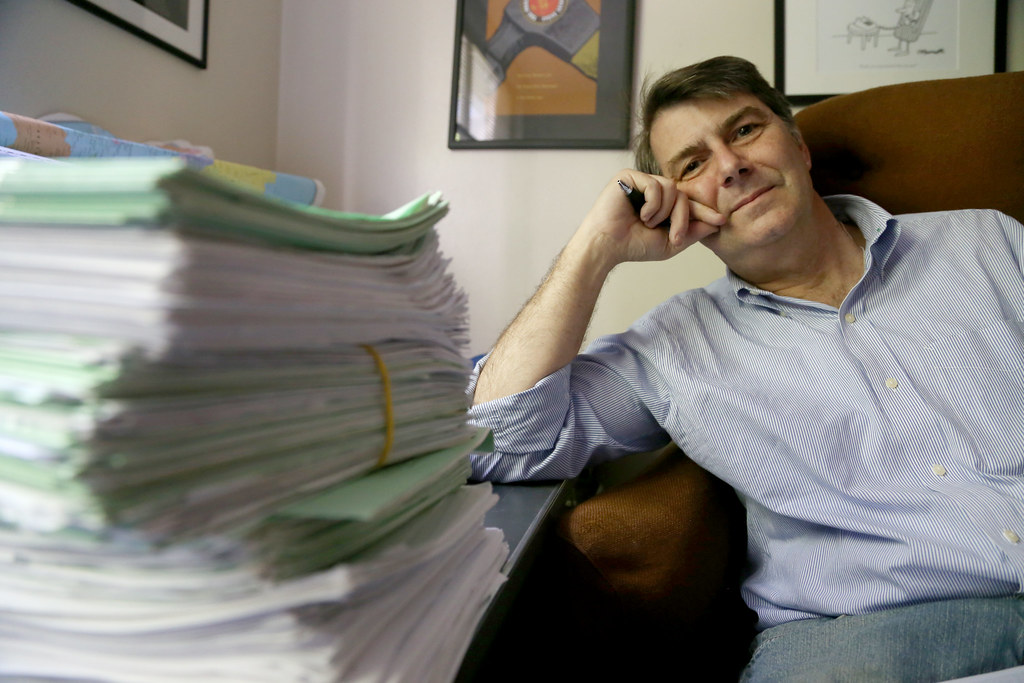

Mark Sigmon, an SF State history lecturer, sits in his office among the hundreds of papers he has to grade in the science building room 221 Wednesday, May 14. Photo by Rachel Aston / Xpress

Mark Sigmon, an SF State history lecturer, sits in his office among the hundreds of papers he has to grade in the science building room 221 Wednesday, May 14. Photo by Rachel Aston / Xpress

Sigmon attributes the growing number of adjunct faculty to CSU hiring lecturers to replace retiring tenured professors. The CSU typically pays tenure and tenure track professors between $65,467 and $93,644 per academic year, almost double the average CSU lecturer’s salary, according to CSU data.

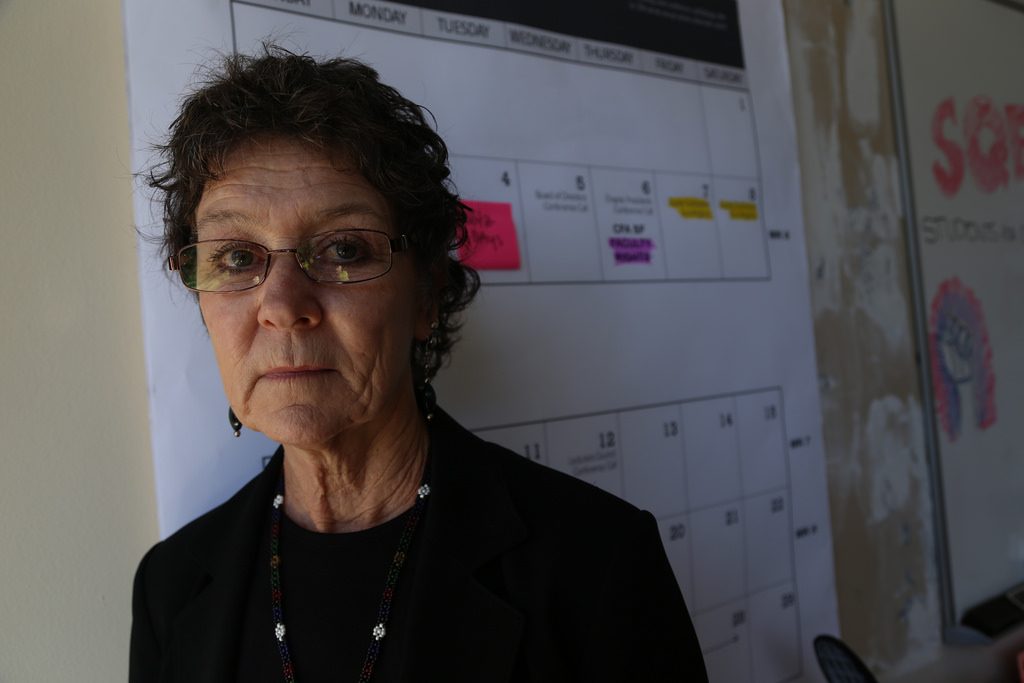

“It’s part of a general tendency in the university to think simply in terms of dollars and cents and not in terms of the function of the university as an institution that’s supposed to embody the value of humanities and the arts,” said History Lecturer Steve Leikin, who traced the root of this issue to a budget crisis 30 years ago, when the university first began hiring part-time faculty.

Steve Leikin, a history lecturer, poses in his office in Science 221 Tuesday, May 20. Photo by Rachel Aston / Xpress

Steve Leikin, a history lecturer, poses in his office in Science 221 Tuesday, May 20. Photo by Rachel Aston / Xpress

Employment instability is a tremendous frustration among lecturers and forces many to seek employment at other universities or community colleges, often resulting in lengthy commutes between two, three, even four institutions.

“They call them ‘freeway flyers,’” Leikin explained. “People who run from school to school just to cobble enough courses to survive.”

English Composition Lecturer Georgia Gero-Chen said she’s lucky to have split her teaching between multiple schools only once, because the practice is common among part-time faculty.

[HTML1]

“Cobbling together a living from various places, leaves lecturers scrambling,” Gero said. “They’re juggling different policy procedures and different curriculum. They’re not as available, and they have to work harder as a result to mitigate the impact on students.”

Still, staying at one school does not promise lecturers any job stability. SF State’s course offerings coincide with student enrollment and CSU funding. A lecturer could teach four classes in the Fall semester, then suddenly be left scrambling when there is only enough room for two of those classes in the Spring budget.

Tully says she often faces this problem, forcing her to pick up suppressed classes, courses the university roll out after they publish the official class schedule, sometimes with less than 24 hours notice.

“It’s extremely stressful. You’re trying to pull together a class and order books. You’re totally unprepared; students think you’re unorganized,” said Tully. “My all time record was picking up a graduate seminar at 7 p.m. on Sunday night, and it met the next morning. I taught it for three weeks without books.”

Suppressed classes are not only unfair to faculty, says Tully, they also obstruct students’ educational needs, as most of the students who end up in classes released at the last minute are those who care little about the subject matter.

Lecturers have little control of their own job growth. Even with a Ph.D. in their field and consistently positive student evaluations, lecturers have no ensured path to tenure.

After Sigmon obtained a Ph.D. from UC Berkeley, he was offered several tenure-track positions at out-of-state universities. Instead, Sigmon took a part-time lecturer position at SF State, hoping he could work his way up to tenure-track. After 25 years, Sigmon has never been offered a pathway to tenure.

According to Sigmon, lecturers are unlikely to work their way up to the tenure track because the university would rather hire a recent graduate with a cutting-edge dissertation or a published best-seller for those positions than reward a lecturer’s job well done.

“I’m teaching five classes, whereas my tenure-track colleagues are teaching three classes and they’re making about $15,000 more a year than I do,” said Sigmon.

Despite pay differences and several responsibilities that accompany having tenure – serving on committees, publishing work, etc. – lecturers and professors do virtually the same work, and the distinction between the two eludes most students.

“My sense is that students don’t really see the difference between tenure-track faculty versus part-time adjunct faculty,” said former Journalism Lecturer Justin Beck. “I think if more students were aware of what’s going on with adjuncts at SF State there would be a push for change.”

[HTML2]

Beck, who was terminated from his teaching position just days before the semester began, says that adjuncts fear that speaking publicly about their unfair working conditions could put their employment at risk.

But there is promise for better working conditions. A nationwide campaign working to empower contingent faculty launched a local chapter, Adjunct Action Bay Area, in January. The campaign helped adjunct faculty at Mills College form a union last week, and they are filing a petition for a union election at San Francisco Art Institute.

Although she has received a substantial raise in more than eight years, Gero-Chen is optimistic about future working conditions for faculty.

“We’re seeing a lot of nationwide movement in terms of organizing part time faculty into unions,” Gero-Chen said. “but lecturers and tenure line need to step up and work together to put pressure on President Wong, Chancellor White and Sacramento to get more funding.”

Tully estimates she works 60 hours a week, including the “invisible labor” university does not consider: creating lesson plans and syllabi, grading papers and meeting with students outside of her office hours. Workload, Tully says, is an issue for all higher education faculty, not just lecturers.

Despite her frustration, Tully does not seek tenure track positions at other universities because, she says, they are only looking for “some young, hot Ph.D. who can bring in a ton of research money.” But for Tully, giving up the profession altogether is simply not an option.

“I don’t make a lot of money, but when my alarm goes off in the morning I don’t hate my job,” Tully said. “Most days I go home feeling pretty satisfied that I’ve done a good day’s work. Do I wish I was compensated for it? Yeah. But you change people’s lives as a teacher, and there’s no price for that.”

David Baxter • Jan 18, 2015 at 12:04 pm

This article is totally misleading. Proper “Lecturers” are usually actually fine, as they make an annual salary and get benefits. Lecturers shouldn’t be conflated with “adjuncts”: the term for part-time, contingent “faculty,” who do have no job security from term to term, etc. In fact, actual, proper lecturers are the solution to many budget woes; however full-time faculty and the AAUP are very concerned about hiring more lecturers (which would be better for the students, better for the lecturers, better for departments, etc.) because if you hire someone that makes $30,000 (which many current part-timers would jump at– they may be making far less than this now, trying to spread classes over many different institutions) to teach 8 classes a year, this suddenly (the concern is) puts downward pressure on the professors who make $100,000. Therefore, there is a perverse incentive to maintain a situation which is bad for everyone (including the professors who have to be a part of departments that may have an rotating army of part-timers of unknown quality) just to avoid introducing such a sizable pay gap. The answer to this is to argue that the pay gap is justified by research output: the professors bring value to the university through prestige and research , and through teaching upper division courses and graduate students with their specialized knowledge and are paid for it; the lecturers on the other hand are also paid a proper and decent salary for teaching.

Kevin Pina • Jun 6, 2014 at 8:20 am

Wow, what a great article about this situation.