The disabled community, particularly those with low vision, don’t have many resources at their fingertips. Solutions are few and far between but apps, along with other adaptive technologies, can provide some help.

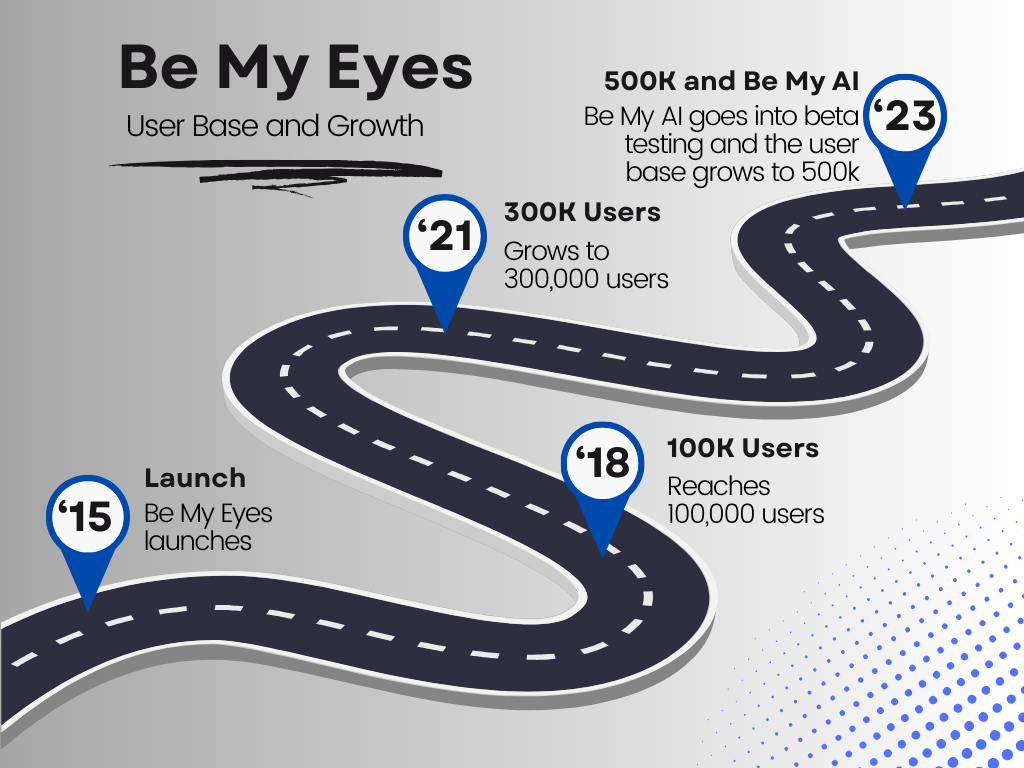

In 2012, Hans Jørgen Wiberg proposed a new phone application called “Be My Eyes.” This technology, created in Denmark, has acted as a bridge between volunteers who would become the eyes of disabled users with low or no vision, but has since evolved.

In 2023, “Be My Eyes” rolled out “Be My AI,” the product of a partnership with San Francisco-based OpenAI which cuts out the volunteer and uses artificial intelligence to give descriptions and read what the user points their camera at.

This kind of advancement in technology can be extremely helpful for the disabled but the speed at which institutions like San Francisco State University adopt them can be a slow, drawn-out process.

SFSU’s Disability Programs and Resource Center (DPRC) acts as a resource center to help make many aspects of attending and working on campus more accessible for students and employees with disabilities.

But according to Kenny Adams, a DPRC disability specialist, the center has not made any plans to implement technologies such as Be My AI at this moment.

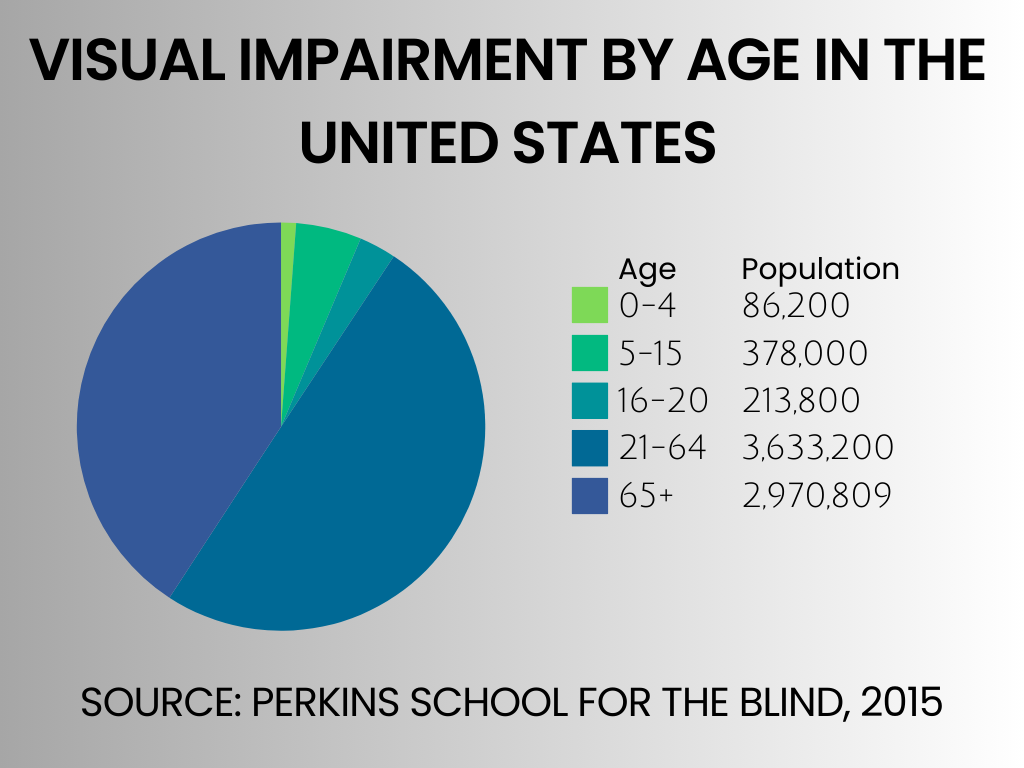

The American Foundation for the Blind reported estimates from the National Health Interview Survey that in 2022, over 50 million Americans over the age of 18 reported some degree of vision loss. Of those 50 million, around 3.8 million have trouble seeing when wearing glasses and 340,000 cannot see at all. Of the initial group, 45.9% reported experiencing minimal difficulty seeing when wearing glasses.

Adaptive technology has been around for a very long time. It is only in recent years that there has been a lot of coverage on it and that is mostly due to the changes in technology that have been seen lately. Until the 2010s, the predominant way that people were reading, especially in the school setting, was through braille, the raised bumps on paper and other surfaces.

The technology available has gone from braille to screen readers and even tools like Be My Eyes. This kind of technological advancement in the disabled community has never happened before.

Today, there are multiple ways for people to receive visual assistance, from screen readers like JAWS, a Windows-based screen reading application to OrCam, a glasses frame-mounted camera that gives live feedback to the user, upon input via gesture. Other companies like Microsoft are also using AI to help the disabled with programs such as Seeing AI.

“The two that we recommend the most are Be My Eyes and Seeing AI,” said Skyler Covich the technology program lead at Braille Institute who holds a doctorate in political science. “Be My Eyes is an app, which started out more for like calling a human volunteer, but they implemented an AI feature last year starting out for iPhone and then now for some Androids… Seeing AI is an older AI that has now added some new features such as being able to describe the overview of an entire room.”

Braille Institute is a non-profit organization that provides services to the blind and visually impaired community in Southern California. The training they provide to use adaptive technologies is at the forefront of the field. Covich formed a partnership with Be My Eyes founder Wiberg and the two entities have moved forward, allowing Braille staff and students to beta test new features in Be My Eyes, including Be My AI, which was rolled out to beta testers in November 2023.

Braille Institute is positioned to not only train the blind and visually impaired to use new tech but also to help steer the direction that that tech goes into moving forward.

“I volunteered to be a beta tester for some of the newer features that they’re adding on to it,” said Manny Hernandez Jr., a Be My Eyes beta tester.

Hernandez only lost his sight three years ago, due to complications from diabetes. A former union rep, Hernandez was always drawn to technology — losing his sight was a huge blow to him mentally and emotionally. Hernandez had doubts about his ability to make a living when he first lost his sight. But in the three years since losing his vision, he has gone back to work in full capacity, but had to stop due to other medical issues.

Software like Be My Eyes and Seeing AI have proven essential for the low-vision community. As of February 14, 2024, over six hundred thousand blind or low-vision users have signed up to use Be My Eyes.

“We actually did a workshop with the founder of Be My Eyes in January; it had almost 100 people attending. What I liked about Be My Eyes is that… you can just take a picture of an entire room. And if you have voiceover on, it’ll just read that out to you with very few gestures that you need to use,” Covich said.

Unlike many pieces of adaptive tech, Be My Eyes is free to users. Currently, there are no announced plans to convert the tech to a paid service. While the software is in beta, the AI portion is currently behind a waitlist.

“But other than that, I mean, listen, we’ve come a long way,” said Jeremy Jeffers, a musician and assistive technology user “From what I’ve experienced, and what I’ve seen, it’s looking very, very promising. There was a time when we didn’t have it, we didn’t have the ability to hold the phone up to picture and tell us what it is — hold the phone up to a piece of mail and it will tell you what’s on the front of the envelope automatically. We didn’t have that. It looks very, very promising. Man. It’s a plus, being a techie. It’s really nice to see this stuff.”

There is currently discussion about the implementation of AI on college campuses across the entire CSU. According to Christopher Bettinger, an SFSU associate professor of sociology, none of the CSU campuses have announced a policy on the use of AI yet.

Bettinger is also the investigator for a survey gauging the relationship that students across the CSU have with AI that was started by San Diego State University.

“This AI survey is basically to put, you know, fuel onto the fire of us trying to figure out what our stance is on AI,” Bettinger said. “We’re not anywhere close to coming up to a majority stance yet. That’s really bad because stuff is rolling out quickly and we need to get our arms around it.”

Without a policy, the CSU system can’t begin to give directions on how faculty should proceed regarding AI. Instructure, the developer of Canvas, the learning management system used for classes here at SFSU, recently announced a roadmap. The roadmap plans to introduce new AI tools, including a new “Ask Your Data” chatbot and discoverability improvements to help students find course materials more efficiently.

However, Be My Eyes has also seen its share of challenges.

According to Andre Schmidt, Be My Eyes’ senior software engineer, the biggest challenge of implementing Be My AI into the app is that the large language model (LLM) that Be My AI runs with sometimes will “hallucinate,” or make up things that aren’t there.

“We actually started looking into Optical Character Recognition on our own thing, not part of the AI model. We haven’t done any development on the AI model, just to make it clear,” said Schmidt.

Another issue the software faced was speed. According to Schmidt, the process of getting a description was very different from what it is now. In the past, the user had to open a prompt, type in a question and then submit the information to the AI. Now, the technology uses a live feed that the user can take an image of and, within seconds, receive a description that they can ask for more detail on.

(Graphic by Matthew Ali / Golden Gate Xpress)

Throughout history, the disabled have always been last in line when it comes to advancements in technology. The screen reading adaptive tech JAWS was originally released in 1989 but didn’t see a release on Windows until 1995, a full decade after Windows was launched.

“I have this theory, like old rich people — the old rich people theory of disability, that the more that people — especially people with money — as they get older, and just become disabled by the technology not keeping up with their needs, they’re gonna complain about it — they’re gonna want to do what they used to do on their computers, or tablets, or cars, or airplanes,” said Anthony Vasquez, digital accessibility specialist. “It’s a weird approach, but that’s my angle to like, why how we might get more buy-in from the general public. it’s going to be a matter of time, I guess. And, people realizing they’re missing out on things they shouldn’t have to miss out on.”

Due to the slow nature of policy on college campuses, people with disabilities are at risk of being left out of the use of technology. Free software like Be My Eyes can help alleviate that but there does not seem to be much talk about that kind of technology yet because the university has yet to come up with a policy on what to do about AI as a whole.

“I would say, if you’re looking for a date, I think you will probably see a campus policy in place by fall 2025. Yeah. That’s lightspeed in academic deliberations and decision-making that doesn’t mean that there won’t be any other decisions made. Academic technology… will adopt some things,” Bettinger said.

According to Bettinger, Academic Technology, led by Andrew Roderick here on campus, is in communications with the Longmore Institute and DPRC. While this will likely be a slow process, the DPRC was responsible for getting SFSU to mandate that their website include text descriptions for all HTML pages in the early 2000s.

Currently, the only policy that seems to exist is that the use of any tech in the classroom that isn’t approved or provided by the DPRC is up to the discretion of individual professors. Things will have to wait until 2025 when an AI policy is expected to be in place.