Through the dark nights when the campus is empty, San Francisco State University is maintained by essential workers who often go unacknowledged by students and faculty.

Approximately 200 Facilities Services employees clean 14 major academic and administrative buildings, quasi-auxiliary and auxiliary buildings and University Housing every Monday through Friday.

Out of those 200, 11% make up the Service and Maintenance employee group. According to the Facilities Services website, corridors, common areas and restrooms are dust-mopped, auto-scrubbed, vacuumed and disinfected daily.

Each of these employees plays a key role in keeping SFSU’s operations running smoothly on a larger scale even though many students and faculty don’t clap for them.

Learning English from the hallways of SFSU

Maria Portillo immigrated from El Salvador in 1983, crossing Guatemala and Mexico by bus. At the time, it wasn’t as difficult to enter the United States, so she took a plane from Mexico to Los Angeles.

“I was troubled because it was the first time I was going on a plane. From Los Angeles, I went to San Francisco,” Portillo said.

When she arrived in San Francisco, she met her future husband of 35 years.

Portillo started working at SFSU in 1999 but she applied six times before getting accepted.

“Maybe because of my language, they didn’t accept me,” Portillo said. “During that time, I didn’t speak English very well.”

She started working at the Lobby Shop, where she was a stocker for 15 years. She had to carry boxes filled with water and drinks. She had a part-time job with Facilities Services and would alternate between both to pay her bills. She would clean bathrooms for the Health and Social Sciences, Business and Library buildings.

“The students helped me a lot when I worked there,” Portillo said. “I would also ask my sons if there was something I didn’t understand. I would tell them, ‘Hey, there’s this word I heard but I don’t know what it means.’ But the ones who helped me out the most were the students.”

Everyone else working there was a student at the time. They would approach her and say, “Don’t say that; say this instead,” which she would repeat after them.

“I would continue until I would get tired and they would tell me, ‘You are very intelligent and will learn. Listen to us and you will learn.’ And exactly that, I listened to them and learned.” Portillo said.

When work would be slow, Portillo and the students would meet in the back where boxes would be stored. They would write down on a piece of paper what they had to learn for the day. The next day, they would ask her what the word was, always leaving her with homework.

“It was a challenge for me,” Portillo said. “When students would ask me where something was, I would only respond, ‘I don’t know.’ But I would remember the words they said and look at what they would grab. That’s how I would learn from people. My English isn’t from school, it’s from the streets.”

Since rent is very high in San Francisco, Portillo has to work to make ends meet.

“I always worked, and when my kids were young, my husband would tell me to leave,” Portillo said. “I would say no because if he wasn’t working where were we going to get money from?”

Portillo is now a full-time employee for SFSU facilities. Her husband, who lost his job during the COVID-19 pandemic when the company he worked at closed, is currently unemployed. He now finds day-to-day jobs as a painter. They have two children, one of whom is an SFSU alum. The other is a teacher.

Wiring the community together

In 1974, Los Angeles high schooler Hal May was invited by a friend to work as an electrical contractor on the side. Making $20 an hour for eight years was the beginning of his life as an electrician after graduating high school.

“Early on, I knew that I wanted to be in the trades because it was good money, real good money,” May said. “Then, I was on a job where we were the first generation of point-of-sale systems for ACRO gas stations where you go up and tap your card, which didn’t exist at the time.”

After he discovered the low-voltage side of the job, he found it to be much safer. There was no fear of being shocked or creating fire.

“It’s a lot easier work,” May said. “I just never looked back and that was 40 years ago.”

He moved with his family from Southern California to the Bay Area in the mid-’80s. He fell in love with the diversity and culture after a trip to Yosemite with his brother. He then found a job working for the second-largest Fortune 500 database company based in the Bay Area. The Bay Area was an open road for him, which is what convinced him to stay when his parents passed.

“Especially if you know anybody that’s into motorcycles you have Santa Cruz Mountains to ride in,” May said.

Motorcycles have been his passion since he was 15 years old. During the summer, he spends time on the dry roads of L.A. on his bike. He is a big fan of beamers, another name for BMW vehicles. He currently owns a BMW K1200GT, his third motorcycle, which is about to hit 130,000 miles.

“Testing the limits of the performance of the technology, which maybe puts you in a bubble of more danger than you’re normally allowing yourself, but that’s the thrill,” May said. “That’s the thrill of getting through that corner that’s really aggressive.”

His motorcycle has heated seats and hand grips, a power windshield and an anti-lock braking system that helps with stability.

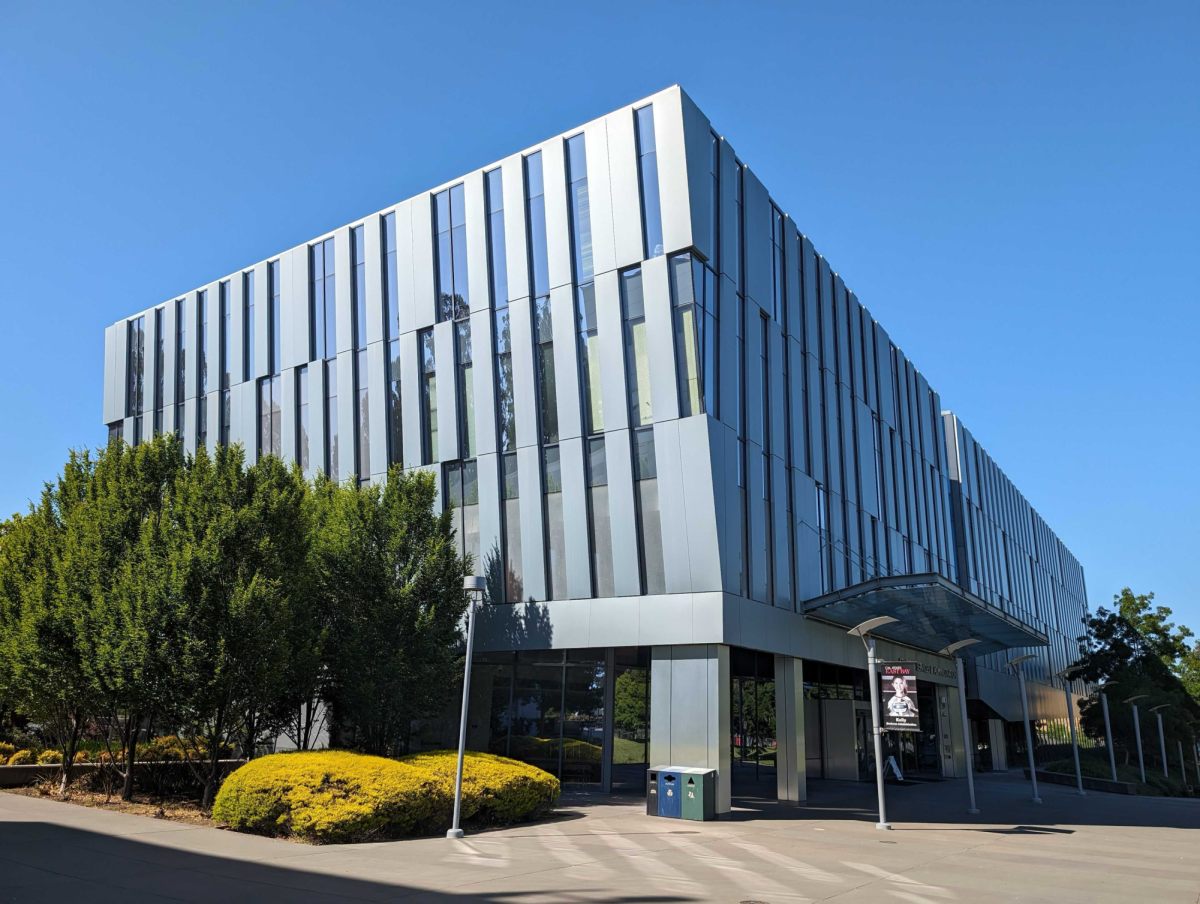

After working for the Fortune 500 company nine years ago, he was offered the job position as a field technician at SFSU. Since then, there has been an increase in portable devices, increasing the demand for his services. So far, he’s worked on three buildings on campus: Mashouf Wellness Center as it was being constructed, upgrades on Marcus Hall, and the new Science and Engineering Innovation Center.

His job is very physical, where safety can be a concern.

“I’m a data plumber,” May said. “You’re having problems with WiFi or something, I’m there.”

ITS is composed of two teams. May’s team is the network side that is composed of six people. Because of him and his team, internet access is available in every building.

After a long day of work, he looks forward to getting home to his wife —whom he has been with for 35 years — and his bike.

“It’s the best medicine if you have something that’s bugging you,” May said. “Once you start the bike, you pull the clutch in and shift the gear. You let the clutch out, whatever was bothering you, you’ve forgotten because it’s now about surviving the ride.”

From Honduras to SFSU

At the age of 75, Orfilia Calderon will be retiring from her position as maintenance facilities at SFSU.

She found this job through a friend when she first immigrated legally from Honduras in 1982. From Honduras, she got on a plane and lived in Texas.

“Back then, it was a lot easier to get your visa,” Calderon said. “The opportunities that are here aren’t available over there. There is a lot of poverty. One has necessities because they have worked for it. You have to add more to life, not deduct.”

When Calderon came to the United States, she didn’t know any English so she attended school in Texas. She remembers learning how to use the verb tense “to be” but prioritized her job more. She attended school for a few months while cleaning houses.

“I started with one house, and after that, they would recommend me to others,” Calderon said. “I became the boss of my own house cleaning businesses.”

Being surrounded by prominent English speakers, she was able to catch on combined with a few years of schooling. This allowed her to get a job at KFC and many other food chain restaurants.

“I learned from the streets,” Calderon said. “I speak a smushed-up English from a combination of words that I would hear and learn at school.”

After four years in Texas, she moved to San Francisco, where she met her husband. Her husband is from El Salvador and he currently drives school buses for young kids with disabilities. After relocating to the Bay Area, she had to restart her business cleaning houses to help her husband with expenses once they started having children.

In May 1987, after speaking to a friend who already had a stable income by working in SFSU Facilities Services, she applied to work cleaning student housing.

“From 8 a.m. to 4 p.m., from Wednesday to Sunday, we would work in groups,” Calderon said. “Some would clean the bathroom, others would do the kitchen, the window, and vacuum to finish an apartment.”

She would clean Mary Ward, Mary Park and other buildings where they were assigned to work.

“Working in housing, you do everything in a group setting,” Calderon said. “When cleaning houses, you have to be checking to not even leave a single hair around. It’s very different work.”

Throughout her years of working, she was moved to clean Marcus Hall for four months during the semester and over the summer to clean student housing.

After her two kids graduated from college, they would ask her to leave her house cleaning job as they didn’t want her mom to be overworked. So she stopped cleaning houses at the beginning of this year. Now after 35 years of working at SFSU, she is looking forward to being at home with her husband, her daughter, and five dogs.

“Now I’m only waiting for death. I’m just looking to enjoy life until the days of life God gives me.” Calderon said.

Her last day working for SFSU Facilities Services will be July 31.