War, poverty and trauma have played a fundamental role in the day-to-day experiences of the Vietnamese American community.

A study showed that Vietnamese Americans, along with other Southeast Asian subgroups, were eight to nine times more likely to develop liver cancer than other Asian ethnic groups and non-Hispanic white people. Based on findings from 1988 to 2011, they also hold the highest mortality rate due to liver cancer.

Another research article found that Vietnamese Americans were one of several Asian American ethnic groups who were experiencing higher mortality rates of cancer and diabetes, largely due to the use of aggregated data collection.

But why is liver cancer such a prevalent issue in the Vietnamese American community?

According to the Alcohol Health and Research World, Vietnamese Americans are at high risk of alcohol problems, with binge drinking being twice as likely among Vietnamese males despite the percentage of Vietnamese and general American drinkers being largely the same.

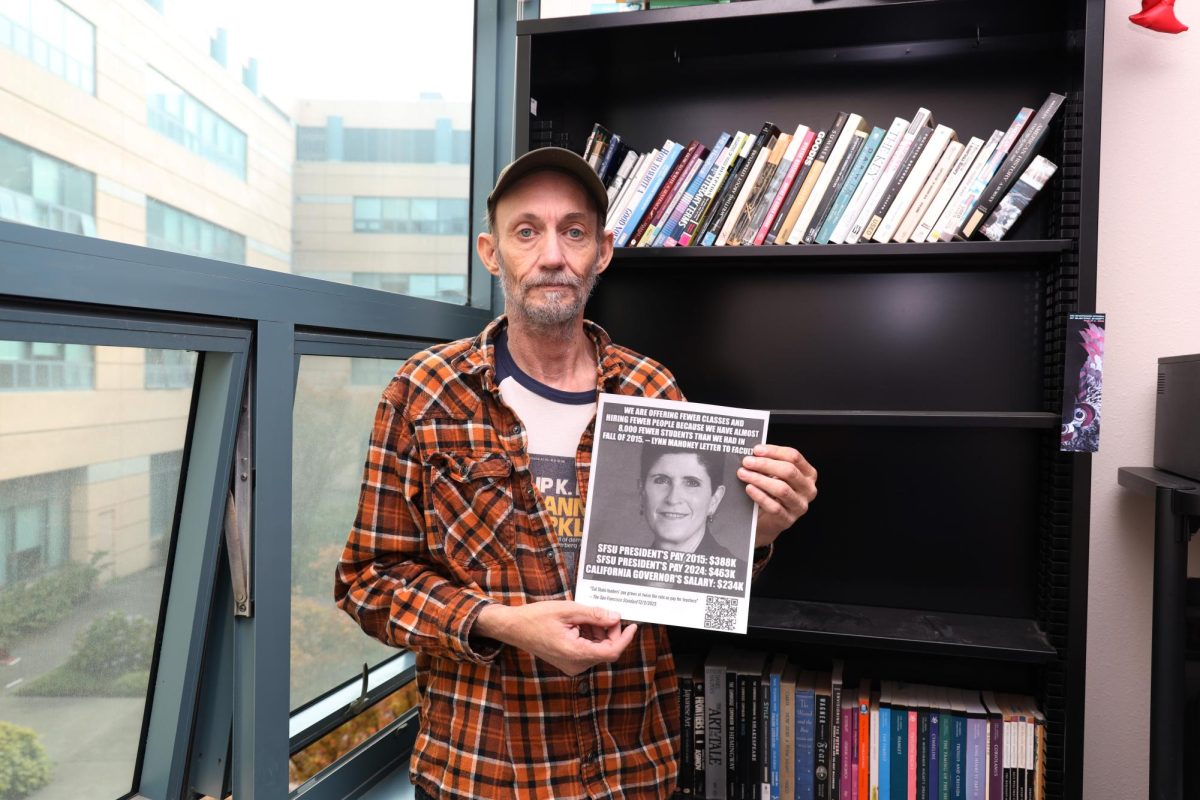

Loan Le, a San Francisco State University faculty member, said that there was an influx of Vietnamese immigration to the United States in the 1970s following the Vietnam War. Initially, Americans felt a sense of responsibility to the Vietnamese but as the number of immigrants increased, that feeling waned and was replaced with “compassion fatigue,” leading to American attitudes toward Vietnamese immigrants becoming more salient.

In addition, Vietnamese immigrants to the United States were separated into refugee camps upon their arrival, which were spread across the country. The community was fragmented, leading to a sense of isolation. Combined with the growing negative perception of their community from Americans, this resulted in higher rates of alcohol consumption among Vietnamese immigrants.

“[There was] a lot of trauma, a lot of responsibility,” said Le, who is a professor of Asian American Studies. “A lot of acculturation [was] required and then a tremendous sense of loss and homeland, a family, a tremendous need to cope and to provide your children with this thing called the American Dream. And life isn’t so easy. And on the other side of that people run out of compassion when it should be a patient process, recognizing that it’s going to be no easier for Vietnamese than it was for European immigrants.”

This issue is compounded, said Le, by the racial stereotypes that shape the perception of Asian American health. The model minority myth, which argues that Asian Americans experience higher levels of economic and social prosperity, has made it difficult to gain proper access to healthcare.

“So among minority and healthy immigrants, they assume we need less help than we actually do,” Le said. “Whereas the perpetual foreigner stereotype and its impact on our health would contribute to either not caring about how we are — because we don’t belong in the nation — or be contributing to negative health outcomes for our population, whether those are mental, social, emotional, or physical.”

Le is also the director of research for the Asian American Collective Action for Racial Equity and Solidarity, which was founded by fellow Asian American studies professor Russell Jeung.

She says that AACARES can be considered the second phase of the Stop AAPI Hate study. The initial efforts were to track and bring attention to reports of harassment or violence against Asian Americans; the second phase aims to navigate the aftermath, according to Le.

“Some of my recent work focuses on what are good and promising strategies to heal Asian Americans. And in that respect, there is an aspect of health inequality,” Le said. “Because if we have a greater need, there is some evidence to suggest that not all allocation efforts are fully considering the needs of Asian Americans, even in government agencies.”

“This also challenges the notion that we have about what it means to be a first class American. If being a first class American means having full access, full rights, then are there people who are being treated as less? And that pushes against the model minority stereotype,” Le said. “The model minority stereotype assumes we’re first class citizens because we’re succeeding in school or we’re getting jobs, etcetera. Nevermind that that excludes many subpopulations that aren’t able to be in computer science or are excluded from that kind of work. That’s particularly at the core or the bottom line of it.”

Much of the health inequality that Vietnamese Americans experience is due to medical infrastructure that does not consider their unique lived experience compared to other Asian Americans.

Alka Kanaya is a general medical doctor and internist in primary care who also teaches and works in clinical research at University of California, San Francisco.

She is a founder and one of three principal investigators leading the MASALA study, which aims to address health disparities in primarily South Asian communities.

Much of her work is dedicated to using disaggregated data to collect medical information, as opposed to aggregated data, which groups together various Asian American ethnic groups under a larger umbrella to make inferences about the entire community as a whole.

“Part of my interest is in seeing the high rates of diabetes and heart disease in my own family and Asian Indian background but also recognizing that there’s a real inadequacy of data in the U.S. because of the aggregation of data that you can’t really see anything like that,” Kanaya said. “So I’ve been working on projects to disaggregate data where possible.”

Due to racial stereotypes like the model minority myth and the barriers that make finding care difficult, disaggregating data on Asian American communities was much more difficult until advancements in medical technology, said Kanaya.

“So that’s what’s nice about some electronic health record data — is that now medical systems are collecting those data so we can actually start disaggregating the larger groups; you still can’t disaggregate really tiny groups,” Kanaya said, referring to smaller groups of immigrants in the Bay Area.

An upcoming cohort that Kanaya is involved in will broaden the scope of what she and her colleagues have achieved at the MASALA study — it will include more respondent groups, aiming for sample pools of at least 1,500 people. It’s a large undertaking, but an important one, she said.

“You need big numbers to be able to do these kinds of analyses,” Kanaya said. “It’s a lot of work, to get funding and to have the staff and have the community outreach to be able to be inclusive. It’s important — without that, you have no idea how things may be different.

“I think that those kinds of studies that have a lot of different groups and disaggregate [data] showing, ‘ Wow, look at how heterogeneous the Asian American groups are,’ and [showing] how we really need to study them — I think that’s really important,” Kanaya said. “Because otherwise things will be overlooked and, you know, we remain invisible.”

The ongoing fight to accurately portray the Asian American community and address health disparity becomes ever more important when considering the speed at which the population is growing.

“Collectively Asian American [and] Native Hawaiian Pacific Islanders are now 8% of the U.S. population, we’re growing in numbers. We don’t need to be — you know, the reason we were all aggregated together, is, you know, back in the ‘70s — This was at U.C. Berkeley — [people were] thinking about policies and having more clout together with the small numbers,” Kanaya said. “But now we have big numbers and we have a lot of diversity, and we gotta embrace that. And we’ve got to get data among all the small little subgroups.”

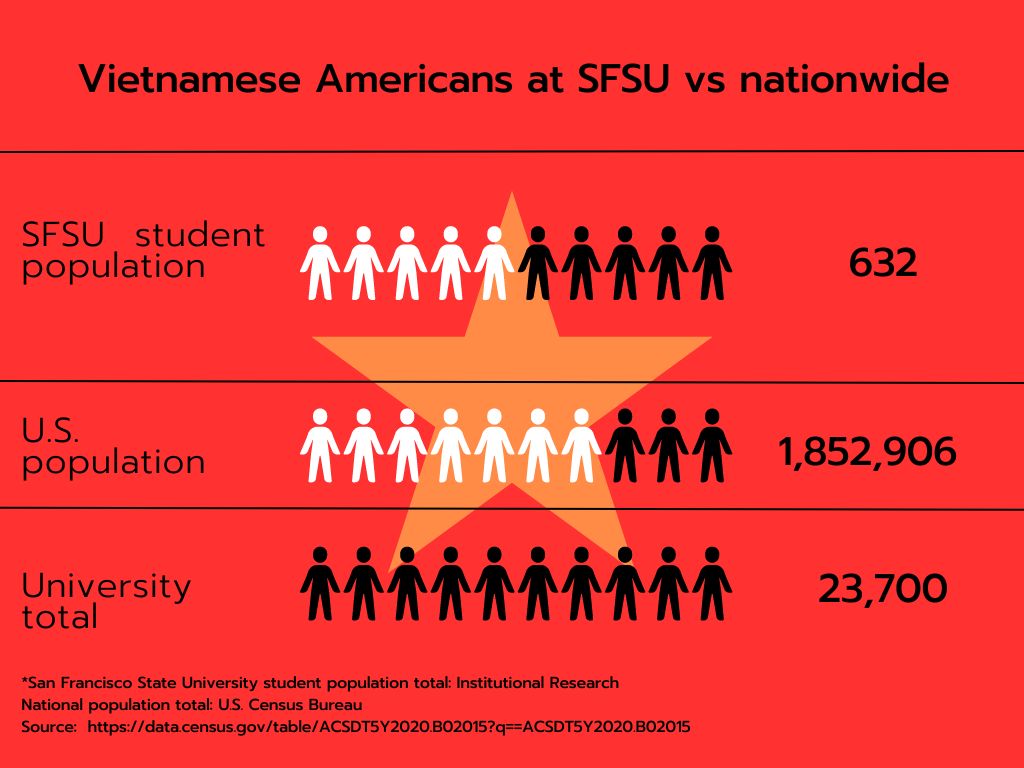

Big numbers and diverse communities in the American population are reflected across the country, but especially at SFSU, which has been designated as a Hispanic and an Asian American Native American Pacific Islander Serving Institution.

Out of the 23,700 students that were counted by the university’s Institutional Research, 632 of those are Vietnamese American as of Fall 2023.

Jacob Vuong is one of the 632, a computer science major who transferred to SFSU last spring from Orange County. He is a member of both the Asian Student Union and Vietnamese Student Association on campus. He says that he joined the cultural affinity groups to help build community following his move to San Francisco.

Vuong said that growing up in an area with a large Asian American population helped him maintain a connection to his Vietnamese and Chinese heritage but that young Asian Americans in Southern California are less politically engaged.

Vuong seemed surprised to hear about the elevated rates of liver cancer in Vietnamese Americans, saying that matters of physical or mental health are rarely discussed in his own family.

“We don’t really talk about the health issues in my household; we don’t talk about, like, ‘Hey, what are some risks that we have?’” Vuong said. “And then when we do talk about it, it’s more just kind of, like, shrugged off.”

Vuong’s own family experiences led to deep-seated mistrust of American systems, extending to healthcare and banking infrastructure.

“I guess it’s just that trust that hasn’t really been built yet, especially for the older generation coming over, because they’re always scared of like, ‘Oh, I don’t wanna lose my money; I don’t want to lose what I’ve built up to this point,’” Vuong said. “That extends to health too, because it’s, like, ‘Do I really trust the government and, like, the doctors that they have in the hospitals?’”

Growing up, his lack of community involvement stemmed from ignorance fostered by Westernization, or growing up outside of his cultural motherland.

“I feel like over here, it’s like, you don’t really get to learn much of your culture until you grow up,” Vuong said. “And that’s when you kind of do your own research, or that’s when you kind of open up to your family about it.”

He said engaging in cultural rituals and events often felt like a burden or a chore.

“Me being very young and very naive and immature, I didn’t really understand the world like I do now,” Vuong said.

Time and maturity has turned the tables for him and Vuong now finds himself urging his own peers to actively engage with their communities.

“I would say that for my friends, I would say that some of them aren’t really active, like how I am. So I try to encourage them, like, ‘Hey, you know, give it a shot. Give it a try,’” Vuong said.

It’s difficult to make people take that first step, according to Vuong. When most of your peers are from the same culture as yourself, he said, it can be hard to see issues that need confronting.

In many ways, failing to participate in building their communities has resulted in many younger Asian Americans being disconnected from them.

“I would say that for some, they’re not really as close to their family compared to me, so growing up, some of them don’t have that relationship with their parents where it’s very close-knitted, or it’s very intimate with them,” Vuong said. “So I guess for them, it’s like they weren’t really exposed to that experience growing up. And so I feel like that really does kind of affect the way that they grow up in terms of their mentality, their mindset, and also just the way they are and how they live.”

But despite the lack of equity and resources for many Asian American ethnic groups in medical research and policy — or because of it — students, community individuals and health experts alike continue to advocate for their communities.

According to Kanaya, the struggle is ongoing. There are systemic flaws in medical infrastructure that allow Asian American subgroups to fly under the radar. But like many things, it’s a work in progress that gives her hope for the future.

“And that’s what we’re trying not to perpetuate — we’re trying to have the data make people and groups less invisible to people,” Kanaya said about the often flawed nature of medical research on Asian Americans. “To shine light on what needs to be highlighted from policy and other perspectives to mitigate disparities.”

Read part one of this series: Filipino Americans are prone to diabetes. Why?

Read part two of this series: Chinese Americans still reeling in the wake of anti-Asian hate