The first patient in the United States to be diagnosed with COVID-19 was on Jan. 20, 2020, in the state of Washington.

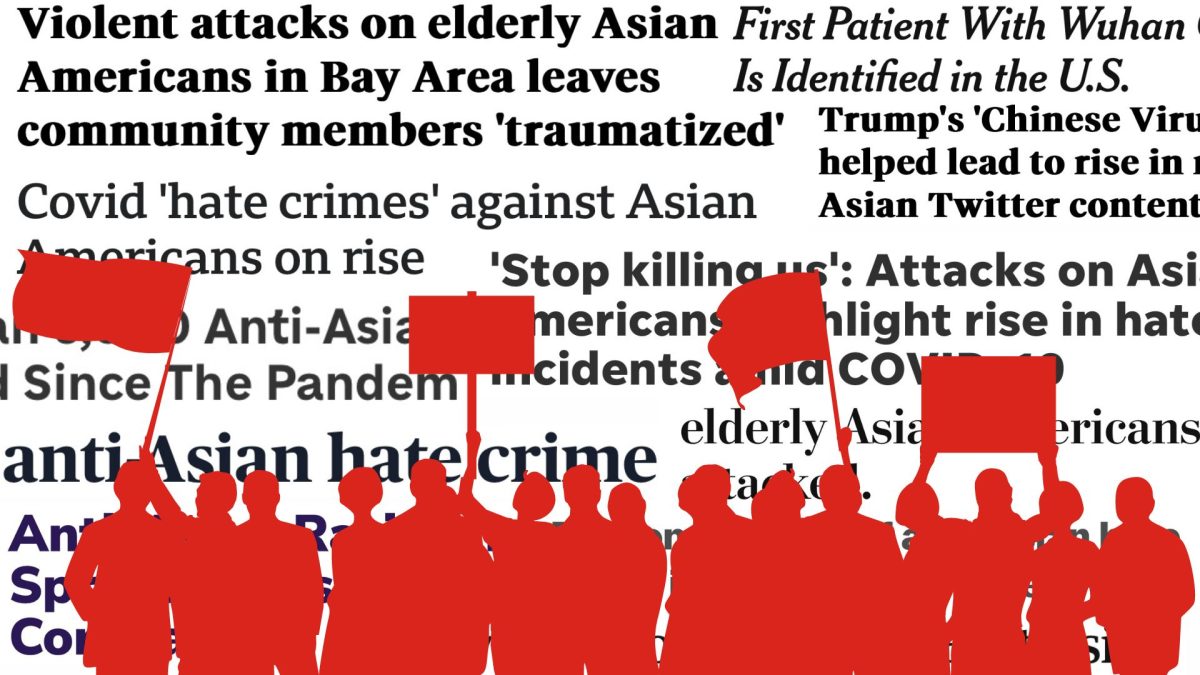

Since then, many Chinese Americans have been affected by the rise of anti-Chinese sentiment during that time, which presented a spike in verbal and physical violence toward the community.

The Stop AAPI Hate National Report, a study conducted between March 2020 and June 2021, kept track of the types of anti-Asian sentiments being reported. It was co-founded by Russell Jeung, an Asian American Studies professor at San Francisco State University.

According to the study, almost half of the respondents were Chinese American and over 60% identified as women, with most being between the ages of 26 to 35.

“When the pandemic began, I noticed an increase in anti-Asian hate incidents, began to track it on news media and then we created an online reporting center,” Jeung said. “That became the Stop AAPI Hate Coalition, and we became [one of] the leading organizations fighting anti-Asian violence.”

Jeung said that Stop AAPI Hate received thousands of reports during the height of the pandemic.

An article published in February 2022 identified three pervasive racial stereotypes that intersect with aggregated data collection methodology to shape Asian American health: the model minority myth, the healthy immigrant effect and the perpetual foreigner stereotype.

The article defines the model minority myth as the perception of higher academic and economic prosperity in Asian Americans. According to the article, it originates from anti-Blackness by positing false proximity between Asian Americans to whiteness, which has traditionally been used to argue against the existence of systemic racism.

Alka Kanaya, a researcher and professor at the University of California, San Francisco, said that the model minority myth is a large part of what continues to mask health inequity amongst Asian Americans.

“If the Chinese who are fifth generation are doing well socio-economically and culturally, they’ve become much more integrated and acculturated and [have] upgraded healthcare and access,” Kanaya said. “That data will show that they are looking like the model minority and there’s a lot of people who will just take that narrative and say, ‘You don’t need resources. Because you are fine. You don’t need to have anything to help improve your health because you’re doing great.’”

With the healthy immigrant effect, Asian American immigrants are perceived to be in better health than their American-born counterparts, according to the article. This conclusion is reached without considering the nuances associated with migration patterns over time and changes in the countries people are migrating from.

Many Asian American immigrants experience lower socioeconomic status, as well as a wealth of barriers to accessible healthcare, according to Jeung.

Jeung said that despite the healthy immigrant stereotype, Chinese Americans can struggle with obtaining proper healthcare due to limited English proficiency, especially older or newly immigrated individuals. The language barrier can make it difficult to explain health issues to medical providers.

“A large proportion of our community is low-income, so they don’t actually have health care. Oftentimes for health insurance, especially if they’re undocumented, our elders are especially affected by the violence and racism,” Jeung said. “So they became more fearful, and won’t go out because of that. That was a major issue of COVID — racism — because they wouldn’t even go to their health appointments, for fear of racism. So that’s actually a documented finding we found.”

The third documented stereotype is that of the perpetual foreigner, which according to Jeung, is a large part of what drove the anti-Asian hate that disproportionately affected Chinese Americans at the height of the pandemic.

“The perpetual foreigner stereotype is that we’re outsiders; that we don’t belong to the United States and that stereotype, along with this notion that we’re the ‘yellow peril’ — dangerous and threatening — led to the COVID [era] racism,” Jeung said. “People thought we were outsiders who didn’t belong, disease-carrying, and so they attacked us.”

Increased violence has fostered fear within the Chinese-American community even after the first COVID-19 patient was identified in the U.S. four years ago, in what Jeung describes as a “collective racial trauma.”

“That trauma has [resulted in a] fight or flight response for a lot of elders in the Chinese American community,” Jeung said. “They’ve fled from the violence, stayed indoors, and that’s led them to greater isolation and not even seeking health appointments. So that’s really worrisome.”

Stella Yi, a health disparities researcher and professor at New York University Longman School of Medicine, said that vaccination rates were staggered in different Asian American communities during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. This was a result of varying social determinants affecting access to resources, according to Yi.

“Vaccination was the highest amongst Chinese Americans, a little bit lower in Japanese and Koreans, and then, like, 50% [lower] in Nepali and Bangladeshi communities, so it was really different,” said Yi, who specializes in studying nutrition and cardiometabolic disease in Asian Americans. “So that helped to activate the local organizations. You know, maybe the Chinese serving organizations can be focusing on other needs, rather than vaccination, and the Nepali or the South Asian serving organizations can be focusing on vaccination and vaccination materials.”

Yi is also a contributing author to the paper naming the racial stereotypes that affect Asian American health and has said that she’s witnessed those stereotypes at play constantly throughout her career.

“The stereotypes — I would, like, live them. I’d be in these diversity, equity, inclusion webinars, and people are just glossing over Asian Americans, over and over and over again,” Yi said. “And I’m sitting there knowing that the data that we collected shows other things but nobody cares about that because they’re all looking at the big data.”

Even now, the conversation about health equity as it relates to the COVID-19 pandemic is one that Asian Americans have largely been left out of, according to Yi.

“I think the other part of it was that this was alongside all the news coming out about how COVID-19 is uncovering all these racialized disparities in Black and brown communities, and we were never part of that,” said Yi. “I think — still — Asian Americans are still not considered to be a COVID-19 disparity community.”

Yi called the process of working on the paper traumatizing — the end product of living through the daily experiences of the COVID-19 pandemic over the course of several years.

“That paper was the culmination of all of that, from six years of experiencing the stereotypes and data over and over and over again — and even in writing that, some of the reviewers were like, ‘Where’s your empirical data to show this?’” Yi said. “It’s like, no, the point of this is that there is no empirical data to show how we feel; this is what the researchers go through every day.”

She says many of her colleagues in the field of medical research remain skeptical of what she and others have observed.

“[The paper] was an invited commentary, but I had to basically put together the story of what I’ve experienced, what we have experienced. But the story is real. [People were] saying, ‘Oh, your lived experience, there’s no data for it, so therefore it doesn’t matter,’” said Yi. “But that was exactly the point of this special issue about racism and health — that, like, let’s get the stories out there that we have not been able to share in the past.”

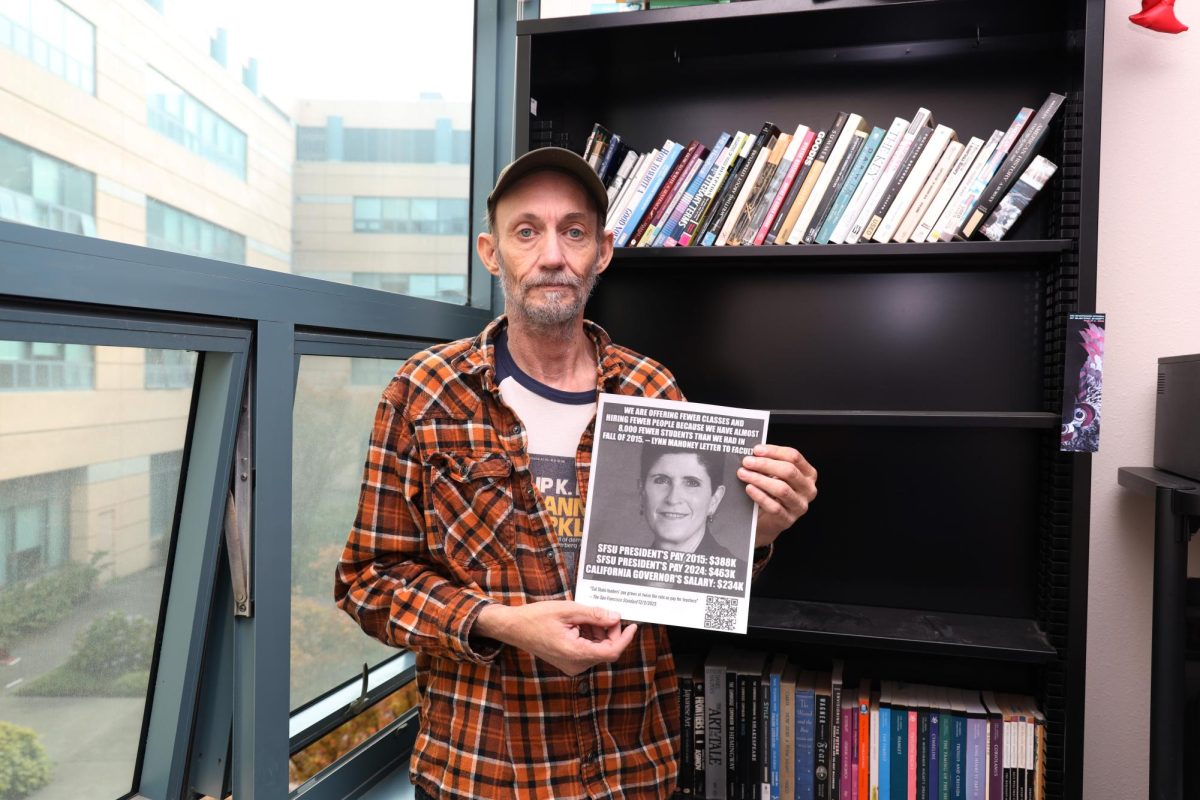

Because of the ways racial stereotypes have shaped medical research on Asian Americans, Yi said that she and several of her colleagues have had to adapt.

“One practice that I do, that I know other colleagues of mine do, is we don’t put Asian American in the titles of our journal articles. If you say [that], it’s like [an] automatic ‘No, we’re not interested;’ that has happened to us for years,” Yi said. “And so a lot of my papers, if you were to do, like, a phonetic analysis of the titles of my papers, they’re pretty broad. Because why? Why can you say you’re looking at healthy diet in Americans, and it’s about white people, and that’s okay, when you have to be relegated to, like, the ethnic grocery store journal of immigrant minority health if it’s about Asia? Anytime [we had] our papers published, we would always get a different response if we had Chinese American or Bangladeshi American in the title versus urban immigrants.”

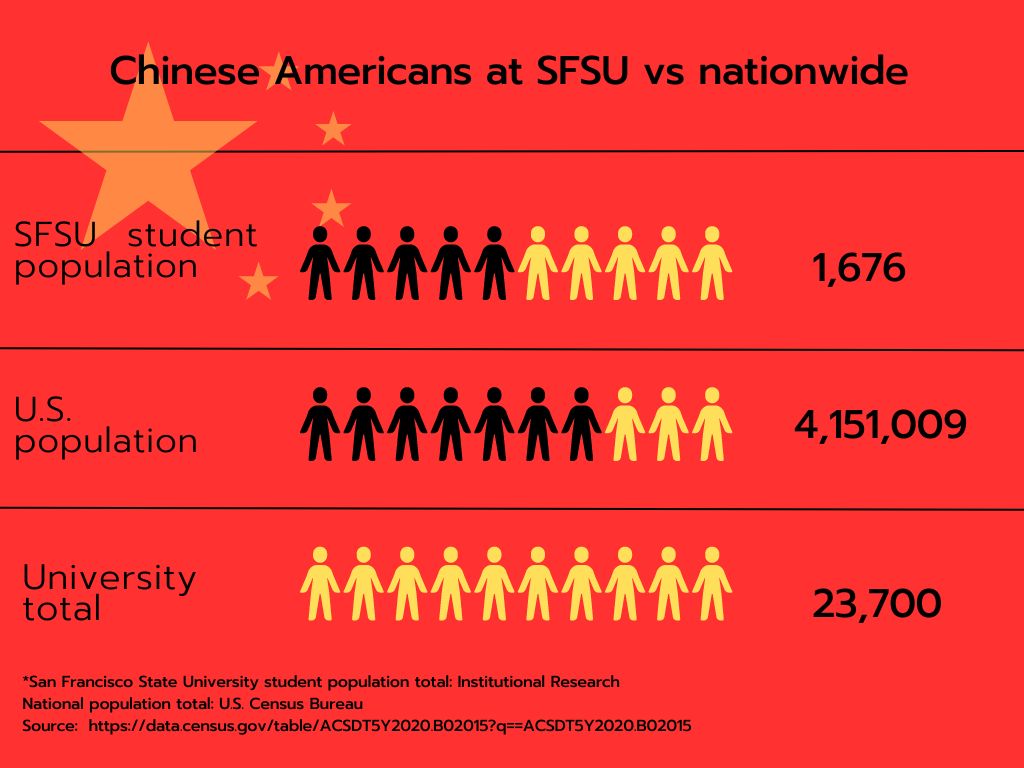

At SFSU, although they are far removed from the medical research scene, many students have been profoundly affected by what they experienced during the pandemic.

Eric Hong, a junior majoring in marketing, is the incoming internship coordinator for the Asian Student Union on campus. He said that the events of the past several years drove him to become more civically engaged.

“A big part of why I wanted to join the ASU was, one, I’ve been wanting to get more involved with the community at school,” Hong said. “I also wanted to get more involved with Asian American communities in general.”

Hong, who was born and raised in San Francisco, said that his family has maintained strong connections within the Chinese American community since his childhood. His father, aunt and cousin are some of several family members who were patrons and later volunteers with the Chinatown YMCA center, which Hong said was part of what inspired him to become more involved in his local community himself.

“I never felt like I didn’t belong. Growing up in San Francisco, there’s so many Chinese and Asian people here,” Hong said. “I’d never really faced racism — maybe some microaggressions here and there but nothing I can pinpoint.”

Hong also attended a K-8 Chinese immersion school, which shaped a large part of his upbringing. But it was his mother’s experiences growing up in a predominantly white community in Philadelphia that opened his eyes.

“The worlds are completely different,” Hong said. “I’m growing up here — I’ll never understand what you faced, but being here is a blessing.”

It wasn’t until the height of the COVID-19 pandemic that the racism that was so foreign to him throughout his childhood became a familiar specter.

“It was super eye-opening,” Hong said. “Being sheltered in such a city like San Francisco, you don’t get to see all this other shit that happens outside of the city. I didn’t know that Asians faced so much hate. I didn’t realize how looked down upon we were.”

Hong said that several members of the ASU have become more invested in having conversations about issues related to the Asian American community as a result of their experiences during the pandemic.

“We always try to bring new topics to light and hopefully educate the people who come to the organization,” Hong said.

Hong said that a personal goal for his tenure includes committing to more volunteer work and bringing speakers, or outside community members, to discuss topics relevant to the Asian American community in order to make younger Asian Americans more well-versed in community needs.

As a transfer student from Los Angeles, Hong said he observed a cultural difference between the northern and southern parts of the state.

“I didn’t meet anyone who was this active and Asian until l came to [SF] State,” Hong said. “I’ve never met so many people so active in climate justice or social justice in general.”

It’s a stark contrast to his peers in Los Angeles, he said.

“You have those people who — I mean, they care about being Asian, but not [to] the extent to where they’re going to do research about it,” Hong said. “Or if a news article pops up, they’re going to read the headline but not read the actual article.”

Hong also confessed his own previous lack of awareness in a moment of vulnerability.

“I know before, too, I would put myself in that category as well, in high school,” Hong said. “Here’s the thing — like, especially growing up in SF — you kind of feel like, oh, Asian Americans are like, ‘Everyone’s here. We’re doing the thing; it’s like everyone’s fine, right? I never really read any articles, never really — well, I volunteered at the Chinatown [YMCA] and stuff like that, but I was not [as] knowledgeable as I am now.”

But the tides are changing, from San Francisco to New York. Aside from becoming more politically engaged in their communities, Asian Americans are also striving to change medical inequity through their work. Yi said that since the height of the pandemic, the health center she works at has seen a boom in applicants.

“The other thing that happened during and post-COVID is the amount of people that want to have internships with our center,” Yi said. “I think it exploded by, like, times 20. Like, they just keep coming.”

Ultimately, Yi said that seeing so many younger Asian Americans working to close the health inequity gap is a reflection of what the Chinese American community went through as a result of the pandemic — and it has the power to affect the future.

“Asian American young people are realizing that they can have a part [in addressing health inequity] — that their experience was not reflected during the pandemic in any way, that their parents were suffering, that their grandparents were suffering,” Yi said. “There are plenty of things that are happening that are good. Having a diverse team matters. If you have a personal experience, [that can] turn into a whole research project and research aim.”

Read part one of this series: Filipino Americans are prone to diabetes. Why?

Read part three of this series: Vietnamese Americans have higher rates of liver cancer compared to other Asian American subgroups. Why?