Swimmers of a young age are thrust into the water to learn a challenging technique: the breaststroke. Only after years and years of professional training does a swimmer become polished enough for an Olympic competition.

With biomechanics, physics is used to analyze performance in order to gain a greater understanding of human movement.

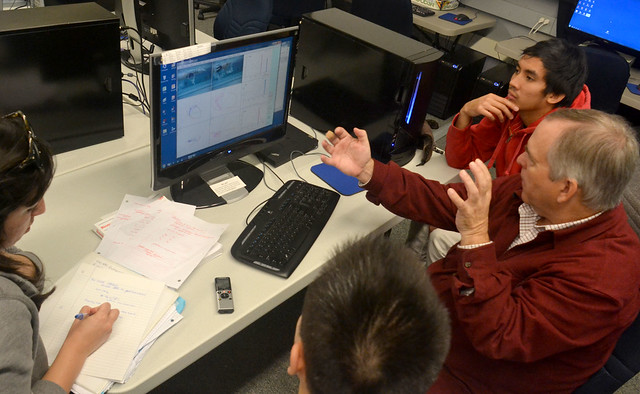

University professor Robert Schleihauf could potentially improve the techniques of SF State athletes through biomechanics, which he said is most effective with sports like swimming, tennis, and track and field.

After joining the staff in 1995 with a background in swimming biomechanics, Schleihauf said he intended to work with the swimming team, but the coach was not interested. Even though the University men’s and women’s conference-competing swimming teams were cut from the athletic program in 2004, Schleihauf said biomechanics can be used to help improve the techniques of other athletes as well.

“The number one thing is to say, ‘Well, identify the one thing you need to do to improve your technique,’ and then ask the coach — and I was a coach as well as a researcher — to go ahead and implement that change,” Schleihauf said. “Now, implementing that change sometimes takes a year, so you can’t do this quickly.”

Basketball guard and senior Michaela Booker, who changed her major to kinesiology at the beginning of Fall 2012, thinks that using biomechanics programs and equipment in college-level sports is not particularly necessary.

“It would be beneficial (but) probably not at the college level because, at this level, all the basketball players already are used to a certain type of way (of doing things),” she said. “You can’t really change a senior’s jump shot anymore — it’s too late. So maybe at a younger age if you teach them to have the right form, the right technique and that type of stuff, it would be beneficial for them in the long run.”

Athletic departments at other universities such as the University of San Francisco have good relationships with kinesiology departments.

Doug Padron, USF athletic performance assistant athletic director, said the University would like to integrate some of the professors as “exercise physiologists” once a science building is built to house more exercise physiology resources for the department.

Padron said biomechanics is important not only to help prevent injuries, but to help improve an athlete’s technique.

“I think there’s a value in (using biomechanics to train) too because you’re doing injury prevention at the same time,” he said. “If you’re identifying how an athlete moves and what deficiencies they may have as a result of that and training them based on what you’re seeing and what you’re able to analyze, they perform at a high level with wellness as their base. I don’t think that’s any different than what (Schleihauf) is talking about.”

Because the study of biomechanics requires extensive quantitative measurements and analysis, computer programs are used to measure this movement. Schleihauf spent 35 years developing a biomechanics program of his own. This program measures an individual’s movements from a video clip and creates movement maps and illustrations that can be used to compare the same movement from another individual, according to biomechanics professor Kate Hamel.

Women’s track and field head coach Terry Burke said using biomechanics programs is not completely necessary to train his athletes since he has been trained in the field. Burke said he completed several courses on biomechanics for his coaches training under the Track & Field Academy for the U.S Track & Field and Cross Country Coaches Association.

“When you’re looking for big changes, you shouldn’t need software,” Burke said. “You should be able to do it by just looking at it.”

An example are key actions emphasized when an athlete sprints. Sprinting is a two-stroke action done under the center of mass, according to Burke.

“So at max velocity I want to see the athlete’s hips as high as possible and very strong and fast down stroke as that is how force is applied,” he said. “When done correctly it is smooth and very silent. I emphasize the latter because a good coach can hear when it’s wrong because the strike will be loud.”

While Schleihauf’s program was available for coaches at no extra cost, Burke said it’s still a matter of finding enough time to use the program with the athletes since they are also busy with school.

“I can get the changes that I need without using software,” he said. “I don’t think that I need to add another layer when I’m getting progress without (it). It’s gonna complicate the process.”

Although Schleihauf said using the program shouldn’t take much time if the user understands biomechanics, he said the biggest problem now is getting the right support.

“In order to get a science, biomechanics (and) kinesiology program to contribute to the welfare and to benefit one another with the athletics program, you gotta get the right people to come together,” he said. “You gotta have coaches that want to improve and use science to improve — not all coaches want that — and we got to have scientists that really, really want to help those people.”

Schleihauf’s own software suite is in use in the University biomechanics lab for free for college programs.

Matt • Aug 9, 2014 at 7:46 pm

This article fails to explore the benefits of sport biomechanics in any meaningful way. Why not examine why coaches are often wary of sport science?

Consider the statement, “Using biomechanics (software) is not completely necessary to train athletes since (the coach) has been trained in the field.” That statement means, basically, “I already know about biomechanics so I don’t need to use biomechanics.” Or, consider this: “You can’t really change a senior’s jump shot anymore — it’s too late.” Says who? Where is the journalistic intelligence necessary to illuminate these basic logical glitches?

What could be discussed instead, is that sport biomechanics as a field is offering science-based solutions to coaches, who are often times the most superstitious, traditional, curmudgeon and technophobic of people.