If I have a perfectly good smartphone with no operational issues, and I decide to spring on the newest, fastest design on the market, what does that make me? For millions of people, it means they became the owners of the new iPhone 5S and 5Cs that recently hit the market.

In our pocket computer generation, access to the Internet and fast mobile browsing is something most of us take for granted — and as a necessity. Clearer resolutions, snappier processors and faster web response all enhance the user experience, whether that’s the ability to take and post the perfect Instagram photo, quickly grab driving directions or swiftly end a trivia disagreement with a friend.

But how often do we need to swap out old gear for newer technology? Data from 2011 Recon Analysis shows that on average, Americans change their phones every 21.7 months, as opposed 46 .3 months in Japan, 51.5 months in Italy and 80.8 months in Brazil.

The desire for newer and better is arguably strong among our generation, particularly in this country. That desire comes with a cost, one that has been dramatically rising in just the last several years. The Wall Street Journal published an article last year highlighting some families that set aside nearly $1,000 to upgrade to the new iPhone 5 at the time. Data from the article shows that the average family’s cell phone bill rose to $1,226 annually in 2011 from an average of $1,110 in 2007.

When we look at our personal necessity and what we actually need as students, can we justify the growing and weighty cost of owning a smartphone? And even if so, what about upgrading to a new phone each time a newer version comes out?

There is no doubt that smartphones in general have a myriad of uses. Like any tool, they have effective purposes. The slew of apps out on the market offer ways that benefit us in daily life: maps, news, financial access, budgeting tools, voice memo recording and increasingly more. At what point does the need to access all of the information rectify the need for a newer phone, or justify the cost of a higher data plan?

Some of us require smartphones for our line of work. Depending on our field of study, our internships or classes will demand that we have some sort of smartphone-benefited tool.

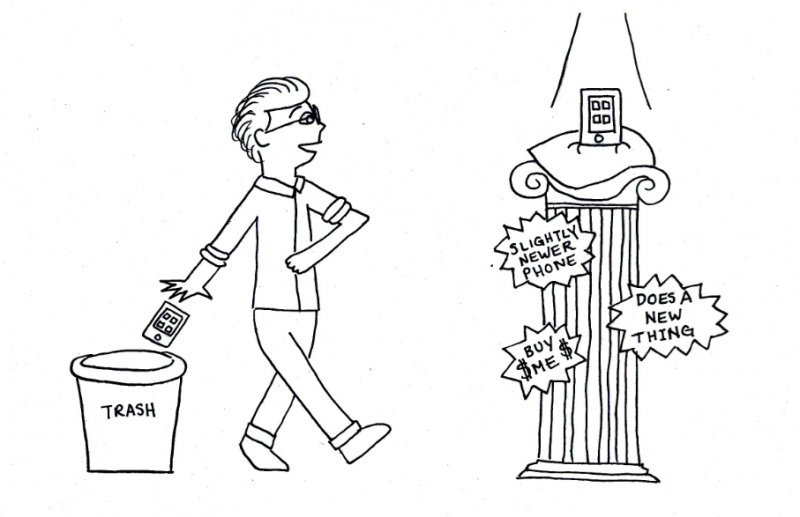

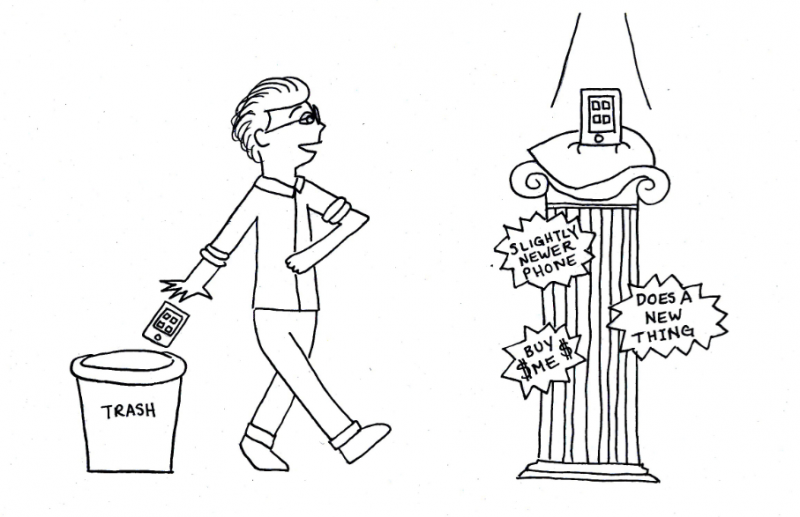

Planned obsolescence, the practice of manufacturers intentionally creating a product doomed to become outdated or obsolete, is definitely part of the problem. An article by World Crunch highlighted the issue across multiple industries, where products are manufactured with failure programmed into their lifetime, and foreseeable costly repairs near or equal the cost of buying a replacement item.

With smartphones that have a limited amount of battery charges before deteriorating, fragile and small jacks that get corroded and worn and hardware that eventually clogs up in speed, the need to replace a smartphone will likely plague anyone that owns one and depends on its operation.

Being able to discern the priority level of such an investment in one’s life is undoubtedly important for students monitoring their spending. The lifelong skill of knowing when and when not to spend money is something that everyone needs to learn. Having the latest and greatest piece of technology may be a definite asset in our jobs and education, but may not serve us so well in the long run if only to quench our need for retail therapy.