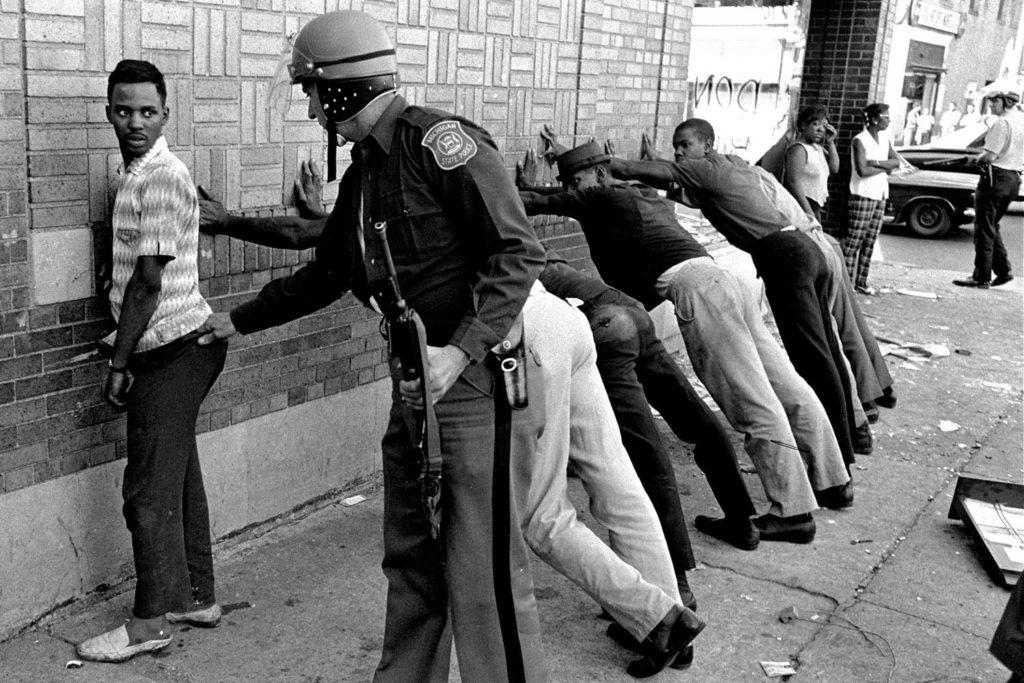

In 1967, cities such as Nebraska, Tennessee and Detroit exploded in riots. The violence was the result of decades upon decades of discrimination against the African American population.

In response, President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed 11 members to the Kerner Commission in July of 1967 to investigate the causes behind the race riots.

The commission issued a report in 1968 that concluded that institutional and systemic racism were responsible for many of the ills that beset African Americans.

The report famously remarked that the nation was “moving toward two societies, one black, one white — separate and unequal.”

On Nov. 14 the SF State journalism professor Jon Funabiki and past journalism professor Bruce Koon formed a panel discussion to talk about the history of the Kerner Commission report and how racism still affects us to this day.

Funabiki said the commission found that the root of these riots came from an explosive mixture of poverty, poor education, slum housing and police brutality caused by “white racism.”

The commission believed that biased coverage from an all-white media was one of the major underlying problems of race relations. The report highlighted the lack of adequate representation among the people assigning, reporting and editing media coverage.

In a diverse newsroom, different perspectives would occur, which could provide a more accurate version of the truth, according to Koon.

“You can’t tell everyone’s story when you don’t have everyone in the room,” said Koon.

Fifty years ago, the commission asked news organizations that were largely white about why they lacked diversity. The response was always the same: that there was a lack of qualified candidates in the minority population.

Little has changed since then. Koon recently conducted a study on whether newsrooms in particular still lacked diversity today.

“I interviewed 14 news organizations representing newspapers, televisions, radio stations and digital new sites, and the number one issue they said that has been preventing them from being more diverse is ‘I can’t get qualified candidates,’” Koon said.

The SF State journalism department worked to address inequities in newsrooms by being among the first universities to offer a class on diversity in the media.

Funabiki and Koon invited the audience to share their experiences of racism in the workforce today.

SF State journalism student Emily Curiel said she’s felt marginalized at times.

“When interviewing people, I felt like they went more toward a white reporter than me,” Curiel said Emily.

The criticism that came from the Kerner Commission led to campaigns to bring diversity to America’s newsrooms. Training initiatives such as the Maynard Institute for Journalism Education and the Multicultural Management Program at the University of Missouri were formed.

Since the Kerner Commission report, minority workforce in TV news has increased seven percent, according to the RTDNA.

With this slight increase, the minority workforce is still “pigeon-holed,” according to Funabiki.

Funabiki recalled from his past newsrooms experiences of being assigned to cover news that only included events of people of his own race.

A USA Today poll found that 62 percent of African-American respondents said that media coverage is more negative than reality, while only 46 percent of white respondents believed that to be the case.

And as existed 50 years ago, there is still racial bias in education, housing, welfare and employment, according to The Guardian.

Among the commission’s solution was creating new jobs for African Americans, construct additional public housing and end school segregation. However the federal government still failed to take the steps necessary to make substantive changes in racial equality, according to The Atlantic.