Seven SF State alumni reunited in the J. Paul Leonard Library March 13 to reflect on the experiences and journeys that led them to participate in the longest student-led strike in U.S. history to reform education and fight for representation of people of color in the classroom.

Speakers included filmmaker Steve Zeltzer, former editor-in-chief of the Black Panther newspaper Judy Juanita, retired international relations professor Margaret Leahy, Asian American Studies professor Laureen Chew, playwright and owner of Rebound Bookstore Joel Eis and authors Peter Shapiro and Ernie Brill.

The speakers described the 1960s as a revolutionary decade for women’s rights, freedom of sexuality and civil rights activism. It was fertile ground for the movement that led to a five-month strike that lasted from November 1968 to March 1969, culminating in the birth of the country’s only College of Ethnic Studies.

Friction on campus emerged in spring of 1967 when students challenged the University’s cooperation with the government in providing students’ academic records to the Selective Service Office responsible for the draft.

That friction turned to sparks in November, one year before the strike began in earnest, when James Vaszko, the editor-in-chief of the Golden Gate Xpress, then known as the Gater, wrote an editorial speaking out against funding what he called “special programs” like the Black Student Union.

Outraged Black students responded by physically attacking Vaszko in the Gater’s newsroom and six of them were charged with felonies. Among those charged were Murray and present-day actor Danny Glover, both students at the time, and they were represented in court by future San Francisco mayor Willie Brown.

Like many of the strikers, Leahy’s involvement in the movement heightened after the newsroom confrontation.

“It was bloody,” she said. “People were really hurt.”

But Juanita and Shapiro said it was the Nov. 6,1968, firing of English instructor and graduate student George Murray, who was also a Black Panther member, that lit the fire behind the strike in earnest.

“In addition to being a childhood friend of mine, [he was] a speaker for the people and for the cause,” Juanita said. “And at that time he was demonized. They fired him because he was outspoken.

“Once we realized what was going on, we had a number of demands, including a Black studies program,” she added.

Shapiro recalled that Murray gave a speech shortly before his termination noting the societal inequity in compelling minorities to pay taxes to support a system that excludes them from its benefits.

“He couldn’t sneeze without inspiring scary headlines in the media,” Shapiro said. “He was fired right before the strike began.”

Leahy said she grew up mostly apolitical, but everything changed when she took her first international relations class, a discipline she would go on to teach for 25 years at her alma mater.

“I realized how inadequate my prior education had been,” she said.

Chew and Brill were among the hundreds arrested during the course of the strike and 50 years later Chew recalled the experience of being hosed against a wall during a jail protest along with hundreds of other women.

“There was police presence on campus every day and they came from other counties, too,” Leahy said. “Hundreds upon hundreds of people were arrested.”

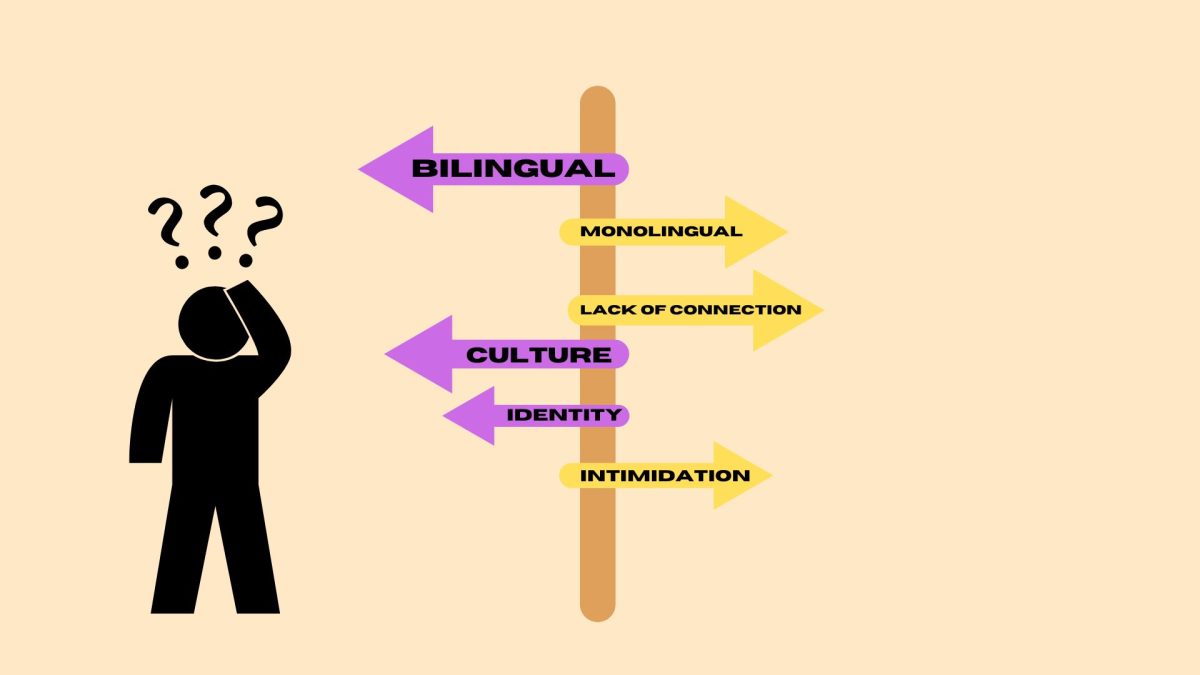

She said her time at SF State helped her understand the anger she felt in her youth toward her own culture.

“I was forced to be Americanized as a child,” Chew said. “I wasn’t allowed to speak Chinese in school and I didn’t understand the resentment and self-hate I felt after high school.”

Brill was arrested confronting then-president S.I. Hayakawa, who turned the sound system off during a protest. Brill grappled with the administrator for the microphone and ended up in cuffs.

Brill later wrote a novelized short story describing his parents’ shock and disapproval after his arrest.

“Students are the most exploited class in American society,” he said.

“The generation gap was more than a slogan,” Eis added. “It was very real, and a lot of us felt that.”

The students weren’t alone in their protest, though. Zeltzer said faculty members formed a picket line in solidarity, and student strikers went in groups of twos and threes to speak with faculty and try to gain support for the movement.

“The strike was the greatest education I’ve ever received,” he said.

Zeltzer played 50-year-old footage from the strike for students at the library event that showed many of the revolutionaries in attendance in action.

Though the student strikers won their demands and changed education at SF State forever, Leahy said the result wasn’t viewed favorably by everyone on campus or in society.

“I knew that there were fellow students in my classes who were not for the strike. I knew I had to go back to class with them,” Leahy said. “We were friendly, but not friends. We didn’t talk about it afterward.

“People aren’t going to learn if they don’t want to,” she added. “You can’t make people see.”

Fifty years after the strike, Eis said society still has a lot of work to do.

“It’s a shame that you need a civil rights movement in a country that’s supposed to be a democracy,” he said.

Today, ethnic studies departments are prevalent in universities all around the nation, but SF State still has the only College of Ethnic Studies in the U.S. and Leahy said there’s a long way to go.

“You have to be active in your learning, the most important thing is critical thinking,” Leahy told students. “We have to understand that there are a variety of ways to view things, [and] kids who are not learning ethnic studies are not learning.”

Correction: In the specialty section of issue Vol 109, Issue 8 published on March 19, 2019 of Xpress, the story poured under the headline, “1968 activists give insight into history of longest student strike,” is not the story that was intended to run. The story that was published was “Coalitions embody need for solidarity,” by Geoffrey Scott from Volume 108, Issue 11. This error is a result of the design team not using Lorum Ipsum placeholder text when creating the page layout. Xpress deeply regrets this error. (March 20, 2019)

Ernie Brill • May 26, 2020 at 3:41 am

In her March 19,2019 article about the San Francisco State stirke , your reporter Julia Costido quotes me incorrectly in a statement i never made. She claims i said that” students are the most exploited class in America.” I nevere said nor would I ever say this. Student are not and never haave been the ‘most exploited class in America. For one thing student are not an exploited “class” or even an exploied ” group”. This phrasing has sthe shallow stench of an infamous essay written by Norman Mailer- “Student as Nigger” that many shallow commentators and slow-tinking dilletantes thought wonderful when it was simply Mailerian balderdash and hooey. It has always been very cleare to me that the most exploited class in America is the most exploited class in Ameria is the African American, Latino/latinx, Asian Americans and native Americans, without a question.