Crowds of students and faculty on the SF State campus held their signs up loud and proud as they fought through a sea of police officers, shouting, “On strike shut it down! On strike shut it down!”

50 years ago at SF State, the Black Student Union (BSU) and the Third World Liberation Front (TWFL) — a coalition of other student groups — made history after leading one of the biggest student-led strikes in 1968. Strikers were driven to have equal opportunity for public higher education and to have a third world studies department to tell the history of the people around the world.

During the time of the strike, the Vietnam War draft forced young citizens into a war that the American public was questioning and protesting. 60% of the nation disapproved of President Johnson’s handling of Vietnam by Sept. 1967 according to a study by Cornell University.

“We were fighting for the real history to be showing in the college, and we didn’t know at the time that it would lead to programs all over the United States,” said Steve Zeltzer, a participant in the 1968 student strike.

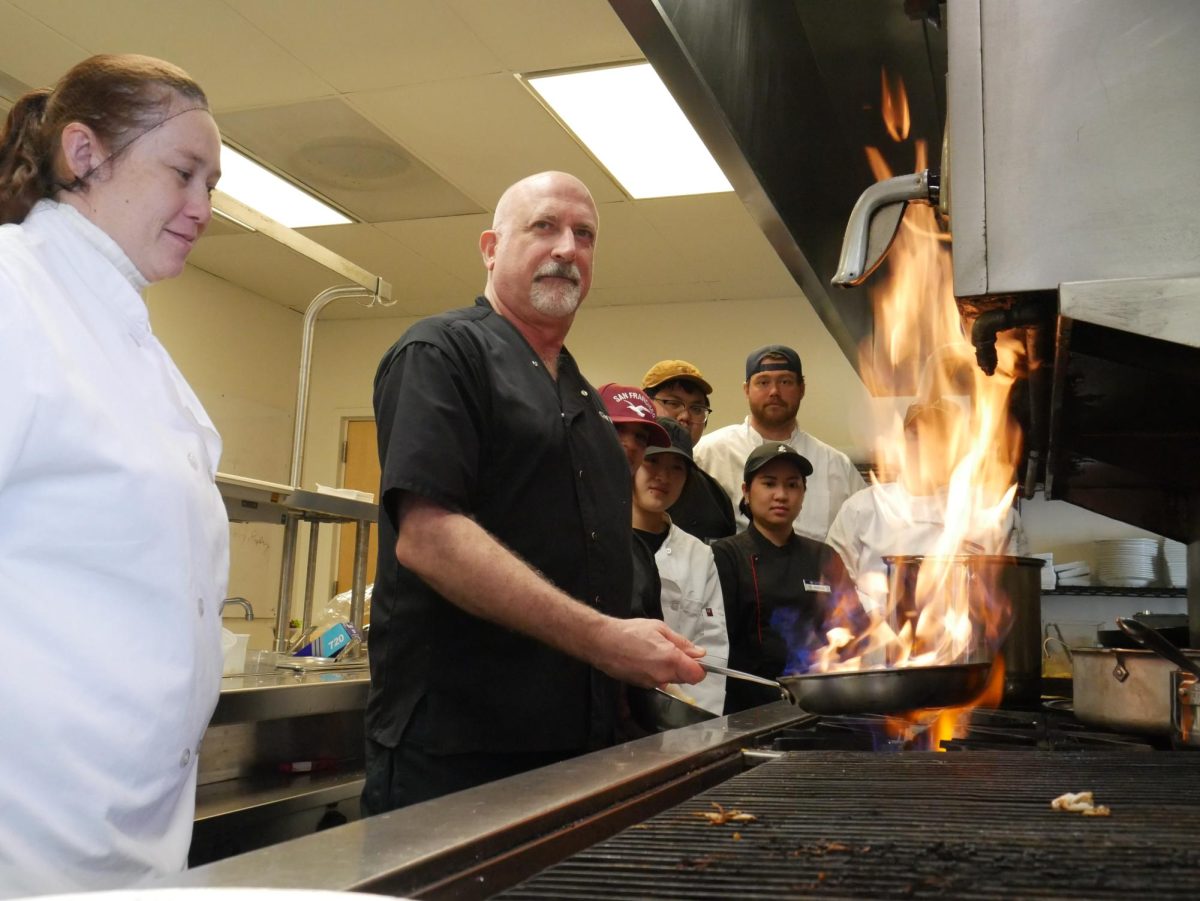

Zeltzer, Steve SF State

Photo from the Daily Gator Newspaper of Steve Zeltzer and Dan Yamshon being taken away from police officers during the 1968 Strike

After graduating high school in 1967, Zeltzer started his first semester at what was then San Francisco State College as a history major. Zeltzer said during his first week struggles between the administration and the students were already happening. A fight for the education of all minorities and a struggle for open admissions to all working-class students going to SF State.

“It was an exciting atmosphere. There were thousands of students involved and professors and people from the community came to campus. It was a community strike, a community labor strike,” said Zeltzer. “That’s why it was successful because you had different communities in San Francisco coming to the campus.”

Zeltzer was part of the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) where students who wanted to fight racism, discrimination and the Vietnam War could organize. Although many student groups were hoping to implement the same changes, they originally did not work together.

“The SDS initially did not want to support the demands of the BSU and the Third World Liberation Front,” Zeltzer said. “But we said, go do it as a matter of principle. And we were able to reach out to the communities and labor to get support for the strike.”

From November 1968 to March 1969, students, faculty and community activists protested for an ethnic studies program for 134 days. Within those 134 days, there was a huge dispute among hundreds of police officers and students. Almost 700 students were arrested and jailed just two months after the strike started — including Zeltzer.

“I was arrested three or four times, but many of them [strikers] were arrested and the district attorney were prosecuting people — so many of my friends went to jail for about six months,” Zeltzer said.

After months of protesting across the SF State campus, the BSU and TWLF signed an agreement with Samuel Ichiye Hayakawa that would meet the protesters’ demands. However, not all of them were met. The administration did not allow the people who organized the strike to be part of the ethnic studies program. The name of the program originally was supposed to be “Third World Studies” but changed to the College of Ethnic Studies.

In September 1969, students were able to attend the College of Ethnic Studies (COES). The strike helped increase minority eligibility and representation across college campuses and started a rise of similar departments around the United States.

After 50 years, the COES provides almost two hundred courses each semester that focus on narratives of Africanas, Asian Americans, American Indians and Latinx groups. COES also gives scholarships to students who major in ethnic studies.

Tomasitá Medál, a student and 1968 strike participant, encourages students to enroll in different ethnic studies programs. Medál said she hopes students take advantage of the ethnic studies classes that SF State provides. She said people deserve to learn the truth and the beauty of people’s cultures.

“If you are Asian American take a Native American studies course or an American Indian studies,” Medál said. “Take advantage that we have a College of Ethnic Studies in SF State because not every college in the U.S. offers it. It’s very special for us to hear about our ancestors.”

The College of Ethnic Studies’ mission statement states that they provide safe academic spaces for all to learn the histories, cultures and intellectual traditions of Native peoples and communities of color in the U.S.

“It’s incredible to think about the College of Ethnic Studies being in existence for half a century,” said Amy Sueyoshi, Dean of COES. “Ethnic studies programs and departments have been under attack since its birth in the late 60s. So it’s incredible to have an entire college, and its longevity has been pretty remarkable.”