The sudden death of a loved one is a hard concept to digest. When that death comes from violence, it is like a pain that cannot go away. For Black people all over the country and all over the world, the violence that we experience and see is inescapable.

Ammar Saheli, co-author of “Eerie Silence: Race/Racism Explored Across Educational, Theological, and Justice Continuums Amidst America and Beyond,” said it is impossible for us to heal because the trauma in our lives is so effervescent.

“I don’t think we can heal, I think we can cope better,” he said. “I don’t think we can actually heal until people leave us alone.”

It will never be as simple as disconnecting or unplugging from reality. One day, the headline might be someone who has been a victim of police violence, like George Floyd, or it can be a family member.

June 7 marked six months since my uncle’s murder. My auntie led a silent protest that resulted in over 100 people contacting the San Francisco Police Department sergeant working on his case to ensure that this murder doesn’t go unsolved. That day, I realized that I have not had the time to process what has happened to my family.

When my uncle met his untimely death, it was supposed to be a day to rejoice. It was the last day of my internship, the fall semester was coming to an end. I had to complete my finals while searching articles associated with the name Mark Coats.

Six months later, we have to see the world in turmoil after another Black family has experienced a loss of the same magnitude. Both of these instances are the realities of the Black experience in this country.

“I think it’s traumatic not only to experience [violence] personally, but to see it happening to your people in the media,” said Tonya Saheli, co-author of “Eerie Silence: Race/Racism Explored Across Educational, Theological, and Justice Continuums Amidst America and Beyond.”

This emotional and psychological trauma that we experience as a community is a recurring incident. It is either another shooting in the community or the police killing another unarmed Black person. Another Black child has to go through life without a parent. Or another Black person doesn’t even get the chance to experience parenthood.

“I think it’s the trauma and the trauma being in a dismissive situation, it’s another layer of trauma,” Saheli said.

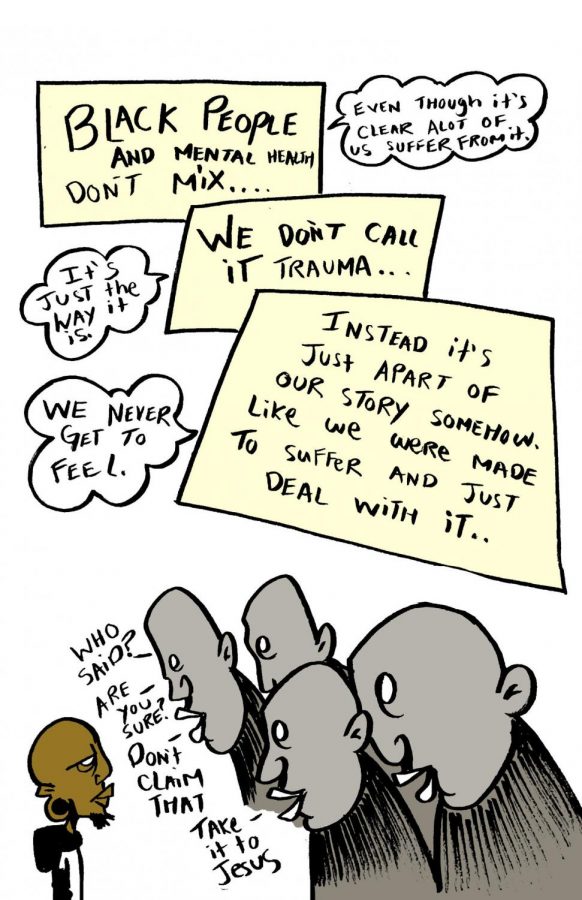

When the idea or experience of trauma is brought up, it tends to be dismissed to make the experience not as serious as it is. On June 4th, therapist and trauma specialist Resmaa Menakem said in a podcast with On Being that the experiences we as Black people collectively have with being a racialized community makes us feel that we are crazy, almost as if our sense of being is altered by our experiences. Yes, violence is something that is constantly occurring, but having to experience it through screens and at our doorsteps is something that cannot be altogether dismissed.

Brittney Holloman, the fitness and wellness coordinator at the Mashouf Wellness Center, talked about learned helplessness being a result of trauma that is faced in so many communities, which is in part a reaction to the trauma that is being faced and causing problems in the healing process as well.

“Somebody that had truly healed themselves is going to be able to have enough wellness, self-esteem, and enough confidence to lift up the community,” Holloman said. “But somebody that feels learned helplessness will not do that. They’ll kind of take steps to take care of themselves first before they can put themselves out there in the community.”

Not only is this learned helplessness a theme that is seen in our daily lives, but this happens in the parts of our lives where we are supposed to be the most taken care of. According to a study from the National Center for Biotechnology Information, 57% of Black patients were given fewer pain medications if they were given any for the same amount of pain that 74% of white patients had. And according to a CDC report on racial and ethnic disparities in pregnancy-related deaths from 2007-2016, Black mothers are two to three times more likely to die from a pregnancy-related cause over white mothers, no matter the education or wealth status.

If no one who is in the position to make change cares about our struggles, why should we as a community?

“I don’t think we can heal, I think that we can cope better,” Ammar Saheli stated.

The topic of trauma brings up the idea of healing. Yet when there is a wound that is constantly being picked at, there is no time for the wound to scab over and take care of itself. That is the aftereffect of trauma in the Black community.

One of the ways that people try to cope with the traumas that are experienced is solo or group therapy, which does not necessarily expel one of the experienced trauma, Saheli said.

Throughout our history, we’ve had to digest not only the traumas we’ve experienced firsthand but also that of the past. This constant trauma is passed on– inherited– from generation to generation. Menakem explained how he understood and felt the trauma of his grandmother when his grandmother told him about how her hands were so fat from picking cotton.

“When we’re talking about trauma, when we’re talking about historical trauma, intergenerational trauma, persistent institutional trauma, and personal traumas — whether that be childhood, adolescence, or adulthood — those things, when they are left constricted … you begin to be shaped around the constriction,” Menakem said.

When there is not an outlet, the trauma expresses itself in different ways. Seeing images of Black people that resemble us and our families getting murdered on film or reading stories of Black people being found hanging from a tree, the only natural response is fear. The other ways that trauma can express itself in what we have seen is the form of looting, protests, defending ourselves, and more violence.

“People need an outlet,” Saheli said. “Our trauma is going to manifest itself in some kind of way.”

Ammar Saheli • Jul 7, 2020 at 2:44 pm

Nice job Nia. Thanks for this work!