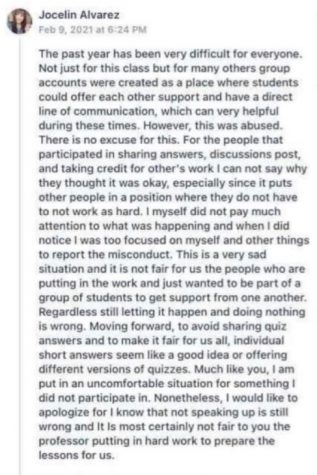

Cal State LA started trending on Twitter in mid-February after allegations of cheating were brought forth by a student in a discussion board on Canvas, an online learning management system.

The student claimed that members of her class were a part of a GroupMe chat where they participated in sharing answers and taking credit for the work of others.

While the allegations drew heavy discourse and surprise over social media, the reality is that cases of academic dishonesty are on the rise, with Cal State LA the latest university to be entangled in a large-scale cheating scandal.

At least 11 universities and higher education institutions across the country have reported widespread violations of academic integrity since March 2020, when in-person instruction was suspended due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The violations were not simply just a few bad apples choosing to be dishonest, but rather hundreds of students at each university engaging in cheating — like at University of Missouri, where more than 150 students were caught sending screenshots in group chats to cheat on exams in three different incidents: one in Spring 2020 and two in Fall 2020.

At University of California Santa Barbara, “The Bottom Line,” the campus newspaper, referred to the issue of students’ widespread use of “homework help” site Chegg and GroupMe across multiple departments as “UCSB’s cheating epidemic” in an article published the beginning of February.

Unapproved utilization of these two platforms are the main ways students are reported to be violating academic integrity.

Chegg offers a paid service called Chegg Study where, for $14.95 per month, users can get access to a database of 46 million textbook and exam questions.

Perhaps the most advantageous service Chegg Study provides is a tutoring system where users can submit photos of tests and assignments to freelance experts in India; Chegg employs over 70,000 people with advanced math, science, technology and engineering degrees, who will then supply step-by-step answers in as little as 30 minutes, according to the advertisement.

Chegg’s stock price has more than tripled during the pandemic, and with 6.6 million subscribers in 2020, the company anticipates growth of over one million subscribers outside the U.S. across 190 different countries.

Chegg’s projected growth is understandable, considering large-scale cheating is not a situation unique to the U.S. Universities in Canada, India, Netherlands and the U.K. have also reported increased violations of academic integrity over the course of the pandemic. So much so that former Universities Minister Chris Skidmore introduced a 10-minute rule bill in the House of Commons seeking to outlaw essay-writing services in the U.K. in an effort to curb the mass-scale use of sites like Chegg.

According to The Hechinger Report, the reason universal online testing has created a documented increase in cheating is because universities, colleges and testing companies were unprepared for the scale of the transformation to online instruction, or unable or unwilling to pay for safeguards.

In an article published by the CSULA University Times, students said they cheated because they feel they were being deprived of their education by having to pay thousands of dollars in tuition every year, including when the world is in the midst of a deadly pandemic, forcing them to receive online instruction.

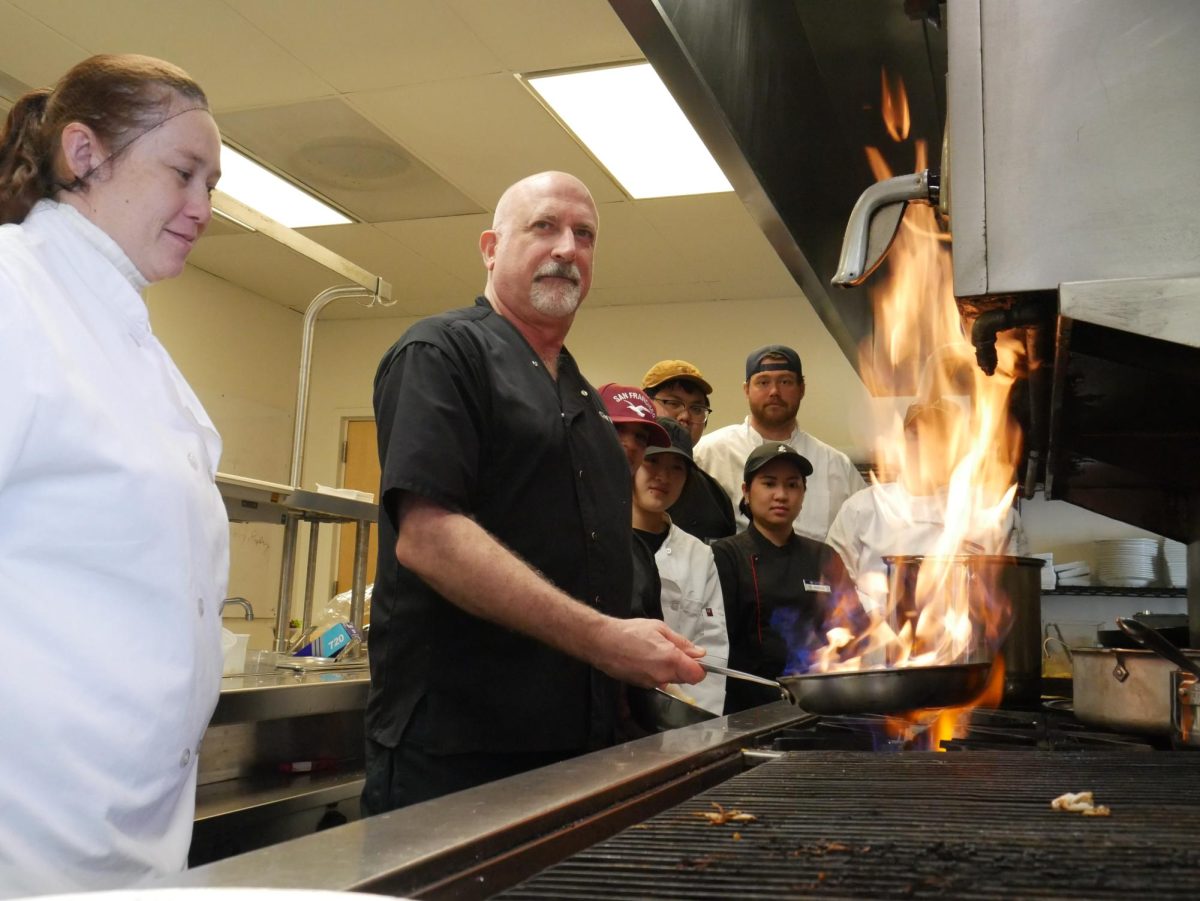

Katie Hetherington, an associate accounting professor at SF State, blamed the remote-learning model for the uptick in academic dishonesty – something she says she had never encountered before in her six years of teaching at SF State.

“Virtual instruction is a very poor substitute for in-person learning. And we, as instructors, have been forced into this model by the pandemic,” Hetherington said. “It really does not serve the best interests of the students. It’s a very poor way to learn the material we’re trying to teach.”

Hetherington said she had four students who cheated on an online exam in Spring 2020 and three students who cheated this past fall, compared to zero cases of cheating in previous semesters when she proctored the exam in person.

“Now that we’re in the virtual environment, there’s really nothing stopping a student from cheating. In my class, I post the exams on iLearn at a certain time, and then they have to return it back to me at a certain time,” Hetherington said. “But, you know, in that three-hour time frame, they could be doing just about anything. I mean, for all I know the entire class could be working together.”

Hetherington also said that SF State’s lack of a university-wide policy for handling academic dishonesty is a big part of the problem. While the university does have a student conduct code that explicitly condemns cheating, each college has its own way of dealing with it.

Although SF State has not had a large-scale cheating scandal since the pandemic hit, it is hard to know exactly how prevalent academic dishonesty is university-wide because not all cases are reported – and even when they are reported, they aren’t always reported to the Office of Student Conduct.

According to Yim-Yu Wong, the associate dean of the Lam Family College of Business, it’s up to the discretion of individual instructors what course of action they want to take when it comes to academic dishonesty. An instructor may choose to bring the case to the department chair, the dean or the Office of Student Conduct. An instructor may also choose to just handle the situation themselves by giving a zero on the exam/assignment or failing the student for the course.

“If the instructor can work [it] out, like handle it, or the instructor with the department chair can handle it, they don’t necessarily have to come to me,” Wong said.

Cynthia Grutzik, dean of SF State’s Graduate College of Education, said that her college doesn’t really have an issue with cheating due to the nature of its learning material. Education courses rarely have exams since they are more concept-based and focused on what knowledge students retain beyond the classroom. Students are typically assessed through written assignments and projects, like lesson plan building, which are then checked by the online plagiarism detection service TurnItIn.

Grutzik is concerned about the prevalence of academic dishonesty in other fields of study and the real-world effects of students cheating their way through college. However, she empathizes with students struggling to learn remotely and understands the increasing temptation to cheat.

“I think it’s just got to be so hard,” Grutzik said. “Even before all of this, I think that it’s gotten way too easy to just share lots of information and there are lots of tools to do that.”

Others feel that no matter the circumstances, cheating threatens the integrity of an academic institution. In the midst of Cal State LA’s incident, recent graduates and current students were angry that the university’s reputation was “ruined” by the allegations, and potential incoming students jokingly tweeted that they were reconsidering accepting their admission to the school.

In an effort to reduce cheating and all of the implications that come with a scandal, some universities are enforcing the use of proctoring services to monitor students during exams. However, third-party programs that utilize both human and automated monitors give way to concerns about student privacy and surveillance.

Tools like ProctorU, Examity, Respondus and Proctorio are common proctoring services used to monitor students’ laptops, tablets or phones during the course of an exam. These tools can monitor eye movements, capture students’ keystrokes, record their screens and track their searches as well as their home environments and physical behaviors.

In September 2020, SF State’s Academic Senate issued Resolution RF20-406, calling for third-party remote proctoring to be restricted or banned from SF State courses starting in the Fall 2020 semester due to equity concerns. Remote proctoring services require students to take their exams in a quiet and secluded location, with a strong Internet connection, a computer that is compatible with the software and additional equipment like a webcam, microphone and speaker. The Academic Senate argued that these requirements were inherently inequitable, especially in the Bay Area where the high cost of living and resulting housing insecurity make private living arrangements and the acquisition of high-tech equipment difficult for some students.

Although the resolution is nonbinding, so far SF State’s Academic Technology department has honored the Academic Senate’s request. Andrew Roderick, director of Technology Services at SF State and chair of the California State University Directors of Academic Technology Group, said that his department recognizes that third-party proctoring is problematic due to both privacy and equity concerns. He stated that although a number of other CSU campuses have purchased site licenses for proctoring services, SF State has not.

“Many [Cal State campuses] very quickly recognized that conditions during remote instruction make it really, really difficult to field this in an equitable way to any set of students in a course,” Roderick said. “Academic technologists and faculty alike have recognized the problem with remote-proctoring.”

He also said that SF State’s Academic Technology department has experimented with third-party proctoring software before the pandemic and found that there is typically a set of students who can’t meet the home setting requirements needed to have an exam proctored remotely, further supporting the Academic Senate’s stance that remote-proctoring is inequitable.

“SF State has been a leader not only in the California State University system, but across the country in this Senate resolution to essentially ask instructors to rethink their approach to proctoring,” Roderick said.

According to Roderick, the few exceptions where the Academic Technology department will facilitate remote-proctoring are for examinations that are required for graduation or required for a significant milestone within a particular program. He said the only program utilizing remote-proctoring right now is the Department of Special Education, where students have a culminating examination required for graduation. The Academic Technology department and Department of Special Education use ProctorU for this exam.

Roderick and Grutzik both believe that instructors should restructure how they access students to minimize cheating and the need for remote-proctoring.

“I think it’s on us to help students see where academic honesty and academic integrity is really, really important,” Grutzik said. “And it’s important for students’ learning, so it’s on us to help students see how important that is and how we can help, how we can maintain fairness and maintain accessibility.”

According to Roderick, how an instructor assesses their students or provides examinations has a correlation with the likelihood of students cheating. He said that from a teaching perspective, there’s a lot of assessment strategies that instructors can implement to reduce the likelihood of cheating.

“High stakes exams that count for a lot of points tend to generate a lot more pressure on students and generate a lot more propensity to want to cheat,” Roderick said. “To really demonstrate competency, you don’t necessarily have to give 100 question, multiple choice sets of tests. There are cases when it’s difficult to do that, but there’s a number of pedagogical approaches that allow you to provide assessment.”

Grutzik agreed, and believes that traditional teaching methods may need to be completely rethought – regardless of who bears the responsibility of students’ academic honesty.

“I think it goes way beyond exams, and it goes just into how we ‘do’ school,” Grutzik said.

At the time of publication, the Office of Student Conduct has not responded to inquiries about the number of cheating cases at SF State.