Following his inauguration, President Biden began staffing a bipartisan commission to analyze reforms to the judicial system and Supreme Court.

The move came after a tumultuous Trump presidency, which added three conservative justices to the high court. However, the prospect of court reform at the federal level has been something left-leaning politicians and activists have advocated for years.

Supporters of Supreme Court expansion believe adding seats, which is known as court packing, is the only practical way to restore bipartisanship to the judicial system.

It’s the solution driving political science professor and activist Aaron Belkin to lead “Take Back the Court,” an action fund that aims to inform the public about the viability of Supreme Court expansion in order to “re-balance the court after its 2016 theft,” as its director.

“In 2016, when Sen. Mitch McConnell and the Republican Senate refused to consider the nomination of Judge Merrick Garland to the high court, they didn’t just steal a seat — they robbed the court itself of some of its remaining legitimacy,” said Belkin in a March article on SCOTUSblog.

This event caused Belkin to found Take Back the Court in 2018, under the name “1/20/21 Project.” The goal of the project, which remains the same under its new name, is to add at least four seats to the current nine on the Supreme Court. According to Take Back the Court, these four seats would not be used to tip the court in favor of Democrats, but rather restore the seats that they allege Republicans intentionally stole.

In 2016, Republicans used hardball tactics to “steal” a Supreme Court seat by holding open the spot vacated by Justice Antonin Scalia for nearly a year so that former President Barack Obama could not fill it. During the Trump administration, Republicans confirmed Justice Brett Kavanaugh to the seat despite concerns about his eligibility from both parties. This disrupted the balance between conservative and liberal justices, tipping the Supreme Court – a traditionally neutral entity – to one side.

Belkin claims that Republicans further proved their intent to turn the Supreme Court after the death of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg in September.

“Last year, when they broke their own cynically contrived rule against confirming justices in an election year to confirm Justice Amy Coney Barrett, they obliterated any facade that the court is above the partisan fray,” Belkin said in SCOTUSblog.

Nicholas Conway, an assistant professor of political science at SF State who specializes in public law and judicial politics, pointed out that it is abnormal to have a majority of the court nominated and appointed by a minority of the country.

“If you look at it in terms of representation, you’ve got members of the court who were placed on the court by presidents, for instance, who lost the popular vote,” Conway said. “Trump is an example of that. George Bush is an example of that […] members of Congress, Republican votes in the Senate, for instance, actually represent a minority of the total population in the United States.”

James Martel, a political science professor at SF State, believes that the impetus for court packing is to counteract the long-term effects of a conservative-leaning judiciary.

“One of the lasting damages that Trump has inflicted on the country is in terms of judges,” Martel said. “Putting very, very highly polarized, very right-wing judges, in not just the Supreme Court, but in the federal court system, too.”

Martel pointed out that these are lifetime appointments, so the partisan court will be ruling on cases for the next several decades. For example, Justice Clarence Thomas was appointed in 1991 by President George H.W. Bush and remains the longest-serving member of the Supreme Court with a tenure of 29 years.

“Long after Trump is – and hopefully is – a distant memory, you’re still going to have these judges who are young judges, who are going to be ruling from a very, very right-wing place for many, many years to come,” Martel said.

The idea of Supreme Court expansion has been met with heavy opposition from the Republican Party, with emphasis placed on adhering to the supposed norm of nine justices and fears that court packing could cause the court to lean to the left.

In January 2021, Florida Sen. Marco Rubio reintroduced a constitutional amendment, S.J.Res 4, that would limit the Supreme Court of the United States to nine justices.

“Packing the Supreme Court is a radical, left-wing idea that would further undermine America’s confidence in our institutions and our democracy,” Rubio said. “As a candidate, President Joe Biden promised to unify America, and even said he was ‘not a fan’ of packing the Supreme Court, a radical proposal he once referred to as a ‘bonehead idea’ when he served in the Senate. If he is sincere about healing our country and protecting our institutions, he will support this effort to protect the Supreme Court.”

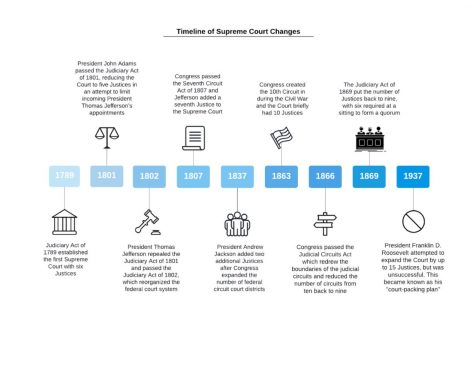

However, the Supreme Court has not always had nine justices, and this is not the first time politicians have proposed to expand it.

The framers of the Constitution created a general outline of the judicial system, with “one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.” The Judicial Branch was established in 1789 by Article III of the Constitution, without any parameters on the size, positions or responsibilities of the courts. As the country grew and changed through land expansion and the Civil War, so did the judicial system.

Aside from President Roosevelt’s failed attempt in 1937 to add new justices who sympathized with his policies to the Supreme Court, the number of justices on the court has remained stable at nine for over 150 years.

Opposers of court expansion credit the fact that Congress has not changed the size of the court since 1869 as a testament to how having only nine justices has become the status quo, a norm that not even FDR could challenge.

Supporters of court expansion argue that this status quo was fine until 2016, when Republicans turned the Supreme Court conservative through their filibustering of Merrick’s appointment, thus disrupting its bipartisan balance.

Realistically, all that is needed to begin the process of expanding the court is for Congress to pass a bill and the president to sign it into law, like court expansion bills of the past. Belkin emphasized the need for the Senate to also eliminate the filibuster, which is a common tactic used to prevent a measure from being brought to a vote.

Some speculate that term limits could be implemented as an alternative judicial reform to court packing. A justice would serve for a period of time, then be required to retire and a replacement would take their seat. According to Conway, there are several proposed formats, and he believes the study that Biden has commissioned will evaluate those different processes.

However, the end result, no matter the structure, would be a rotation over time of justices in and out of the courtroom.

“That, theoretically, at least according to reformers, would make the court more closely aligned to what the present democratic position is,” Conway said. “In other words, it’s closer to what the people’s preferences are at this present moment in time, as opposed to let’s say, you know, a justice has been on the court for 35 years.”

Conway believes that while effective in theory, term limits are a less viable reform than court expansion because Article III of the Constitution makes no mention of term limits and actually suggests that federal judges be lifetime appointees. This means that term limits would have to be imposed through a constitutional amendment, rather than by a simple act of Congress.

“There’s a real constitutional question as to whether they can accomplish that,” Conway said. “Of course, the irony is, who would ultimately make the decision as to whether that statute is constitutional or not? The Supreme Court. So the likelihood of a currently conservative governed Supreme Court saying, ‘yes, it’s fine to impose term limits on us’ and handing over effectively the reigns of the court to the liberals I think is about 0%.”

However, Conway agrees with Belkin and Martel that expanding the Supreme Court is a feasible reform since it can be accomplished through a regular statute.

“It is possible for Congress to expand the size of the court now, but whether they can and whether they should are two different questions,” Conway said.

Biden’s commission is set to come up with a report on its findings this summer, within 180 days of its first public meeting. The White House briefing that details more information about the study and the experts chosen for the commission can be found here.

According to a report published April 14 by The Intercept, House and Senate democrats plan to present legislation to expand the Supreme Court on Thursday. This story is developing and will be updated.

gary fouse • Apr 17, 2021 at 3:45 pm

And if the Republicans take back the White House and Senate 4 years from now, they can introduce legislation to expand the court further, say to 17 justices so they can regain the majority of conservative justices. When does it end?