The impacts from a law that changed the industry forever were still reverberating, then a global pandemic hit.

September 8, 2021

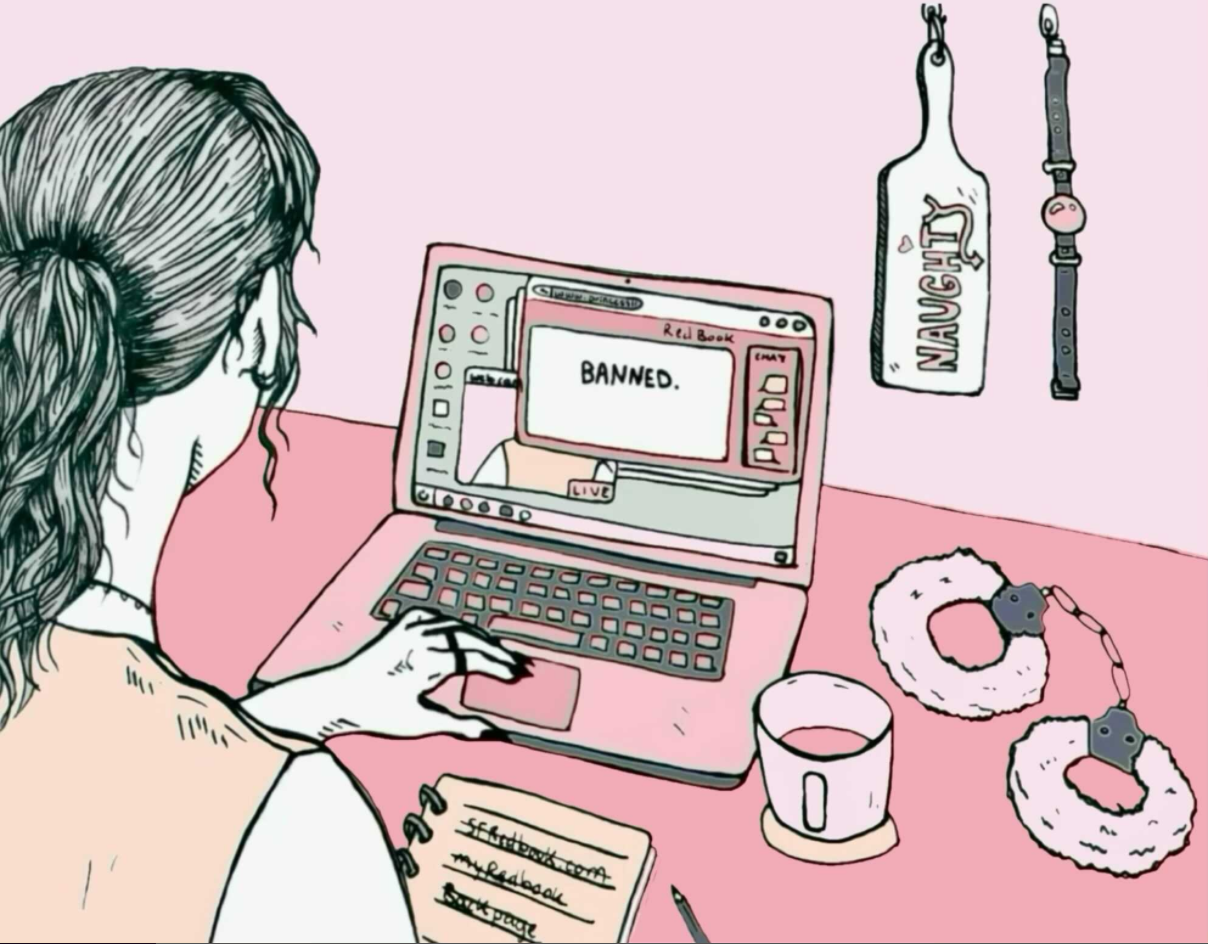

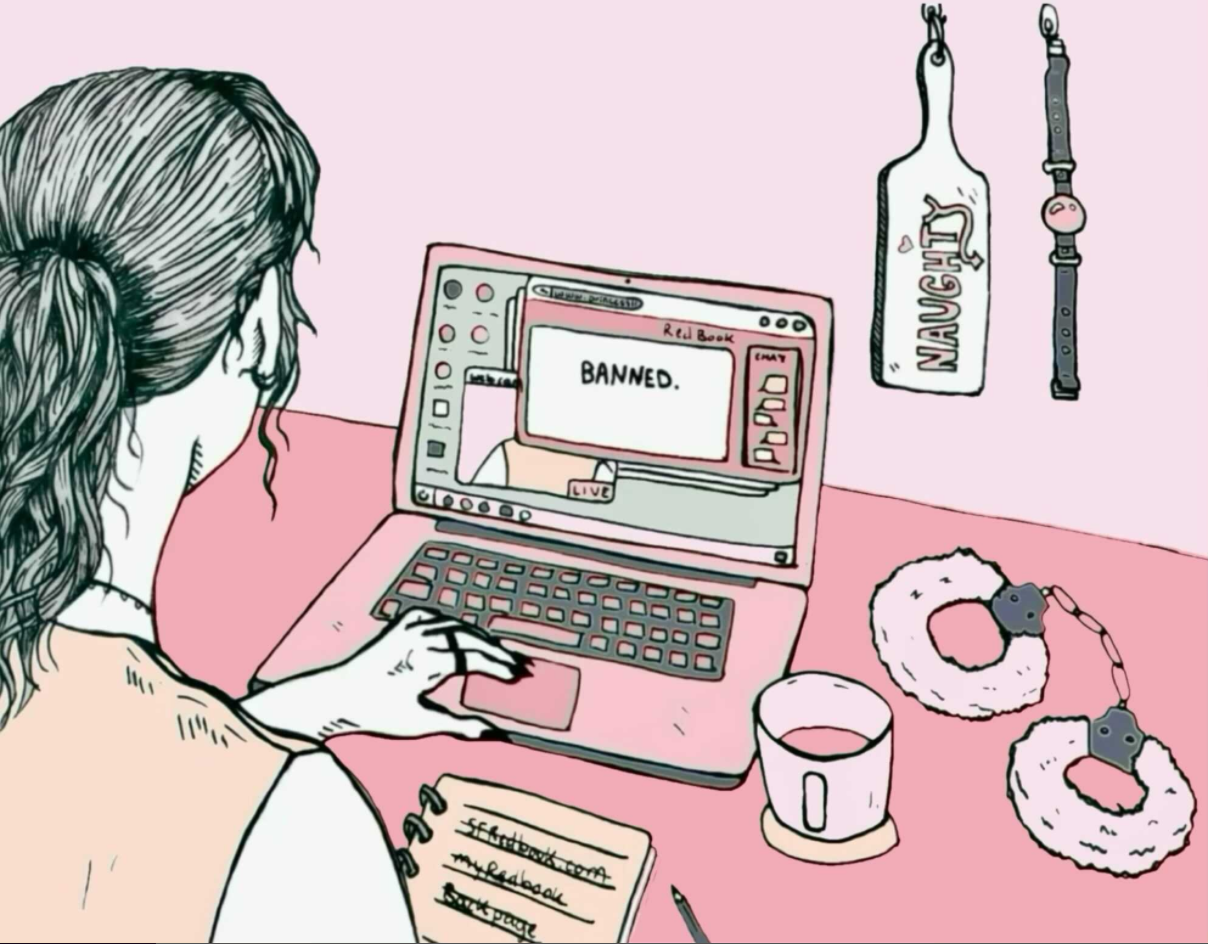

Kristen DiAngelo was posting her services on a sex work advertising site known as SFRedbook.com one day in 2014. Rather than the links to forums, reviews and ads she was typically met with all she saw was a gut-wrenching message:

“This domain name has been seized by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.”

The longtime sex worker from Sacramento explained, “It was like one more time they did it again. They did it again; people are going to die. And to tell you the truth, people did die.”

Four years later former President Donald Trump signed the set of bills known as SESTA-FOSTA, which created an exception to no longer protect website publishers. Previously, Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act (CDA) guarded websites from being held responsible for what their users posted.

SESTA-FOSTA created an exception in Section 230, and now website publishers would be held responsible if users posted ads for prostituion, including consensual sex work.

The amendment’s verbiage states that prostitution and trafficking were always connected, and that websites had become “reckless in allowing the sale of sex trafficking.”

However, sex workers advocates argue that the law has instead made it even more challenging to track traffickers by taking away their database of traffickers and, in the process, has destroyed the digital landscape sex workers had built for their industry.

That federal crackdown, which started with SFRedbook in 2014 and came full circle with SESTA-FOSTA in 2018, has now made advertising digitally a cryptic nightmare. On top of that, a global pandemic has only exacerbated that increasingly difficult environment for sex workers to navigate, while many feel forced to put themselves in situations they would have previously refused.

my website was up before Wells Fargo had a website.

— Kristen DiAngelo

Before she was involved in SFRedBook, DiAngelo — who now is the executive director of the Sex Workers Outreach Project in Sacramento — said she was one of the first women to create a website in the U.S. that hosted sex workers and allowed them to advertise back in the early 2000s.

“We basically patterned ourselves after sites we saw in Europe, where sex work is decriminalized or legalized,” DiAngelo said. “People in the sex trade were some of the first people to have websites. And to make a point on that, my website was up before Wells Fargo had a website.”

The internet gave sex workers a safe space to connect with people from long distances and made it easier to become individual entrepreneurs compared to working on the street, she said.

DiAngelo described that time as an amazing period where sex workers more than survived, they prospered. Going online expanded their customer base out of their cities, into the rest of the country and beyond.

“I could go to any city and tell people I was going to be there and work and do fine. In fact, I could go to almost any city around the world and have that same result,” DiAngelo said.

Outside of individuals’ sites, more prominent services and advertising websites started to emerge such as Backpage, a classified advertising website, and Craigslist’s Personals section.

In San Francisco, SFRedBook.com, also known as myRedBook.com, emerged as one of the leading sex work advertising sites on the West Coast.

As these sites became more established, they started to make more money and the city, state and federal government started to take notice, according to DiAngelo.

The first one to take the brunt of the eradication was SFRedBook. In 2014, it was hosting about 15,000 ads a day, DiAngelo said. Anyone could post for free, allowing the most marginalized workers a space to advertise.

Then one day in June 2014, it was all gone. The Department of Justice had seized the site and all its assets.

Another casualty of losing SFRedBook was the loss of MyPinkBook, a database where sex workers compiled a list of predators, robbers, rapists and “bad dates,” according to DiAngelo.

This was only the dawn of the dismantling of the digital sex work industry.

In 2015, the California attorney general at the time, Kamala Harris, was approaching the end of her run as AG, a title she held from 2011-2017. She was in the midst of spearheading an investigation into the website Backpage, which Harris claimed its revenue was sourced directly from prostitution ads.

But Harris ran into a dead-end known as the previously stated Section 230 that protected internet publishers from facing legal consequences for anything their users chose to publish on their sites, despite its legal standing.

Now enters SESTA-FOSTA. SESTA — the Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act — as it was known in the House of Representatives; and FOSTA — the Fight Online Sex Act — as it was known in the Senate, was created specifically to circumvent Section 230.

I think this generation of sex workers is going to be permanently traumatized.

— Kristen DiAngelo

Maxine Doogan is the president of the Erotic Service Legal Education and Research Project, a group that looks to protect the erotic community and their rights to privacy through legislation. For over 33 years, she has been working as a prostitute, which is a term she prefers over what she considers the vague designation of sex worker. She sees the amendment as a way for the government to regulate their speech.

“It criminalized our free speech, disincentivizing having our ads or our presence on the internet. It also went a step further in that it criminalized other legal types of sexual free speech. What we think of some of the legal parts of the sex trade, like people who are selling their underwear,” Doogan said.

Before SESTA-FOSTA could be enforced on some sites, they preemptively shut down. Craigslist, which could afford to lose that part of their business, closed down their Personal Ads section. Smaller sites had no choice but to shut down completely.

But it was the people working in the industry who felt the direct effect of SESTA-FOSTA.

Since the passing of the amendment, DiAngelo has heard an endless stream of accounts from women who hadn’t worked in years that were forced back onto the streets and young women taking their sex work to the streets for the first time.

“We heard from a woman who had to jump out of a car because she was hustling in a way she wasn’t familiar with and had no way to check resources,” DiAngelo said. “I think this generation of sex workers is going to be permanently traumatized.”

Just like with the closing of SFRedBook years before, sex workers again lost tools to track and protect themselves from dangers such as physical harm and involuntary subjugation.

According to Doogan, a significant problem with the law is it treats victims of sex trafficking and consenting sex workers the same, which they are not. Doogan also contends there is no evidence the law has done anything to stop trafficking or if there was any trafficking on these sites to begin with. The Golden Gate Xpress cannot confirm or disprove that last claim.

DiAngelo believes it has only made it more difficult for the victims of trafficking to seek help and hasn’t really affected the traffickers.

The passing of SESTA-FOSTA impacted the already marginalized communities. Sex workers who don’t speak English, who have disabilities or who are transgender have all faced added obstacles and dangers that, before, they were able to circumvent online.

“If you have a physical disability, how are you going to get people to you?” DiAngelo said. “People who don’t speak English…you don’t have that time to try to communicate with the person to try to figure out if it’s safe or not. You do it over the internet, [and] you have time; [if] you’re on the street…you’ve got 15 seconds to figure it out.”

With the removal of these protections, sex workers have also been forced to do things they would’ve refused before. Doogan said that clients are now requesting more frequently unprotected sex, and because workers are desperate to make money, they don’t feel like they can refuse.

“When you criminalize things, you take away people’s right to say yes, and you take away their right to say no,” Doogan said.

Now, if you want to work as a sex worker and still take advantage of the technology at your disposal, it has become a practice of encrypted or coded messages. Social media platforms Facebook and Instagram screen conversations. If there’s any perceived solicitation, accounts can be deleted, according to Devin Bell, a 36-year-old sex worker from Southern California who has had accounts banned by both.

When you criminalize things, you take away people’s right to say yes, and you take away their right to say no,

— Maxine Doogan

Bell has completely changed the way she now advertises and communicates with clients via private message. She spells words like “seggs” instead of “sex” or “t!ps” rather than “tips.”

Anything that involves the queer community or ads about sex education, even if their ad had nothing to do with sex work or trafficking, is now at risk of federal reprimanding, according to Doogan.

The law stripped companies and publications from the liability that protected them before, leading to sex education companies like O.School to remove all talk of sex work from their platform.

For some people, like Valerie Ronin, sex work has been a savior. After losing her job as a bartender in Southern California due to the coronavirus pandemic, she decided to make the leap into the sex work industry.

“It’s not easy, as some people think it is, at the top. You have to work; you have to pay taxes. It takes work. Sex work is work,” Ronin said.

The 36-year-old, who conducts business over OnlyFans and does not meet clients in person, posts anything from lingerie photos to explicit hardcore porn that she films with her partner.

After losing her job in March 2020, she wanted to spend more time focusing on her two children and moved to Wisconsin. Her youngest has anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder, so she and her partner chose to move back to his home state. He got his old job back, and she got to stay home with her daughter — all while making about $3,000 a month on OnlyFans.

But sites like OnlyFans are not the solution for all.

“Unless you’re somebody who has that technology, has the capability…it’s not going to help you at all. It’s not going to help the marginalized group,” DiAngelo said.

For sex workers who have an undocumented status in the U.S., something like OnlyFans — which requires you to pay taxes — is not even an option. This leaves them vulnerable to police interactions if they move to the streets, according to Phoenix Calida, the communications director for SWOP USA, which is located in Washington D.C.

Calida also explained why for sex workers with disabilities, a site like OnlyFans might not be an available option. They may only be able to claim a certain amount on their taxes, and successful OnlyFans users will tell you just how much time and effort is required to keep a steady following; and that’s not even considering the physical toll that it may take on the worker.

For those who do have the ability to join on websites like OnlyFans, they are not alone. Droves of new creators have flooded these sites, creating an oversaturation that is diluting the market.

“I think it’s mostly harder for the newer folks to try to break out and become more popular, because it is oversaturated. A lot of folks have made accounts and put some content out there but just aren’t making enough to justify keeping it going,” Calida said.

As a result, many sex workers have been forced to stay out on the streets and are left to continue to risk their lives. COVID-19 is just an added hazard.

“We’ve been pretty much decimated,” DiAngelo said.

Prostitutes are not eligible for unemployment, and they definitely do not get pandemic assistance from the federal government.

“A bunch of us had to rely on our family members who paid our rent, who helped us out. Everybody I know who survived it all had family members who chipped in, who gave us money. And customers, I had customers that gave me a whole bunch of money,” Doogan said.

With all of these factors making it more difficult and dangerous every day to be a sex worker, there have been some positive moments that further the conversation for better working conditions for sex workers. These instances worth relaying have primarily come from sex workers pulling together to support each other or from associations like SWOP or St. James Infirmary.

And from the clients, some who have gone out of their way to help many sex workers. Either they send unsolicited tips, or others have paid their bills, without receiving or requesting any services.

“I have definitely seen many workers tell me that when I ask how they are, they say, ‘I’m truly blessed. I can’t believe that people have come together to help me. And my clients have made sure that I’ve had food and that I’ve been OK.’ You know, there are some really amazing people in the world,” DiAngelo said.