San Francisco State University early education student Paola Ramirez often finds herself on guard whenever she’s in a public space. She’ll start eyeing the nearest exit, planning her escape just in case someone enters with a gun.

“Sometimes, I’ll just be in a class and I’ll be taking notes, and then all of a sudden I’ll get a rush of fear,” Ramirez said. “Even in the movie theater. I’ll get a rush of fear of, like, my God, someone could literally just walk in and start shooting.”

Throughout the 23-year-old’s academic journey, Ramirez has experienced two school lockdowns, one at Los Cerritos Elementary School and another at South San Francisco High School. At the time, she didn’t understand what was happening. However, memories of school threats, coupled with news coverage of school shootings, have heightened her fear of being in open, social spaces.

Ramirez — and most other students at SFSU — are part of an age group sometimes called the “Columbine generation,” a title referring to the context of their upbringing, wherein many of these students grew up witnessing or hearing about a steady barrage of school shootings. As part of their educational journey, they’ve grown accustomed to active shooter drills and been trained in “Run, Hide, Fight” protocols.

According to data collected by The Washington Post, there have been at least 404 school shootings and 357,000 students who have experienced gun violence since the 1999 shooting at Columbine High School in Colorado.

The number of school shootings has continued to rise. According to the [3] Indicators of School Crime and Safety: 2022 report, there were 188 reported incidents from 2021-2022 and the number of shootings in elementary and secondary schools was double that of the previous year.

Due to the rising trend, students face emotional and psychological risks due to the fear of an active shooter threat.

Perception of fear

Many schools have implemented active shooter drills into their safety training. But unlike the often forgettable fire and earthquake drills, these campus threat scenarios can linger in young people’s minds.

A study conducted by the Pew Research Center surveyed students aged 13 to 17 during the time between the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting on Feb. 14, 2018 and the 19th anniversary of the Columbine High School shooting about two months later.

The study found that 57% of students expressed concern about a possible threat on their campuses and roughly 64% of nonwhite teens expressed a higher level of worry, compared to 51% of their white peers.

Fears of school shootings also differ by gender, with 64% of girls saying they’re worried about a school shooting compared to 51% of boys, according to the study.

Adolescents develop emotional regulation processes from an early age to control their behaviors in different situations and experiences. This includes situations involving the fear of a threat in social spaces, where feelings of uneasiness are common expressions of emotional regulation.

Madeline Holcomb, an SFSU psychology professor, teaches adolescent psychology and explains that emotional regulation differs between adolescents and adults. Younger people often struggle to comprehend what’s happening in emotionally distressing moments and can feel overwhelmed by not being able to navigate their emotions.

“Of all this news and schools across the country, it’s really difficult on our emotional processing center because we’re trying to work out, you know, how do we process stressful events?” Holcomb said. “How do we process negative events? And the more and more we’re packed on with these negative events, it creates, like, this overwhelming feeling for adolescents.”

Holcomb believes that media coverage of past school shootings, which are often reported without closure, contributes to the fear of threats.

“Most of the time, for adolescents, if they’re seeing these things repeated and repeated on media, and we don’t see past kind of the big events when the school shooting happens, there’s so much media coverage on it, and then there’s nothing right? We’re just left,” Holcomb said. “And that’s really difficult to our emotional processing, because then the story is kind of left out open, and we’re flooded with another experience as well.”

Holcomb points to cultivation theory, which suggests that frequent exposure to mass shootings in the news can shape adolescents’ perceptions and interpretations of reality. She believes that extensive media coverage of violence can lead to an expectation of it.

“So if they’re seeing these things over and over again, they’re kind of shaping their world and what is around them, and they may see violence more and think that it’s more acceptable,” Holcomb said. “So, I think that might play a part heavily in the way that we portray [violence]. And I don’t know what the right answer is either of portraying these school shootings — I think it’s every person should know lives were lost.”

Campus safety concerns

In December 2023, a professor who was denied a job at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas opened fire. Three faculty members died and one was injured.

Allister Dias, a UNLV economics major and editor-in-chief of the student paper, was in the campus newsroom on the third floor of the student union when he noticed police activity on campus. Dias heard police sirens outside the balcony and noticed around 50 people running across the road and between cars down by Maryland Parkway.

“I had a gut feeling that something that was going on, but I mean, you don’t really think it was going to happen,” Dias said.

The sound of six gunshots confirmed Dias’ suspicion and his initial emotion was a mixture of fear and confusion.

“I didn’t want to believe it,” Dias said. “That was the most predominant emotion that I had: fear and confusion. You hear about mass shootings all on TV, and you read about them in your history books. But you never expect it to actually happen to you. And then it happens. And then it’s kind of like — it just breaks your conception of safety.”

Months before the shooting, Dias noticed that several parts of the campus, such as the Frank and Estella Beam Hall (BEH) of the Lee Business School, lacked camera access in certain areas, making those places feel less safe than others.

“I recall having a discussion with one of my classmates about the safety of the BEH and the fact that there’s no cameras,” Dias said. “And I recall saying verbatim, ‘You could stand in the middle of the age and shoot someone, and they wouldn’t ever find you.’ That was my quote. And that ended up coming true.”

Annie Vong, a senior political science major at UNLV, has always felt safe on campus and never feared active shooters. She said she thought the university campus would be safer from shootings than her high school.

“I was kind of just grateful that I graduated high school because I was like, ‘Oh, I’ll be on campus; there’s not that high of a risk of school shooters there,’” Vong said.

Vong feared an active shooter threat in high school because she believed some students might lash out as a result of bullying.

“But I guess [in] college — I don’t think there’s a lot of those pent-up emotions; you’re not with the same [people] in every single class,” Vong said. “So there’s not the same kind of bullying that happens.”

Emotional responses after a school shooting

According to an article by the American Psychological Association, people who have experienced mass shootings may encounter post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and anxiety. The severity of symptoms may depend on their proximity to the incident and whether they knew people who were injured or killed, the article said.

Some individuals can even experience secondary trauma through exposure to others’ traumatic experiences, even if they weren’t actually present.

Dr. Megan Ranney and Dr. Rinad Beidas, both psychologists, mentioned how social media plays a role in secondhand trauma in their personal essay, “Generation Parkland: How mass shootings are affecting America’s children — and how we can help.”

“Thanks to Twitter, Snapchat and 24-hour news channels, it’s possible for youth and their parents who are far-removed from an incident to feel like they’re experiencing the trauma first-hand,” they wrote.

Vong wasn’t on campus grounds the day of the UNLV shooting. She was on her way to school when she received a call from her sister warning her about an active shooter on campus. At that moment, Vong immediately forwarded the message to her classmates and friends, concerned for their safety.

“It was, like, this first gut feeling where it’s just — I couldn’t stand anymore,” Vong said. “I had to — I had to sit on the ground. That hour when I was texting my friends, like, I couldn’t — I don’t know; I felt like part of my body shut down.”

Although Vong was not physically at the incident, she still felt uneasy and anxious. She constantly kept herself updated through social media and news media outlets.

“You can’t do anything, honestly — after the first couple of days after, like, I tried to go to some work and couldn’t do that either,” Vong said. “And I tried to do club work and nothing — paralyzed.”

Vong struggled with her emotions even a few days after the shooting, feeling like she couldn’t be affected if she wasn’t present.

“I saw a lot that it was, like, just survivor’s guilt — where it just felt you have no right to feel this way,” Vong said. “And even though I wasn’t on campus, I really did feel like I had no right to be emotional; but seeing the pictures of gunshots through the exact windows that you’ve passed and the doors that you’ve walked through is kind of harrowing.”

Dias had never thought that his campus would be the scene of a shooting and as soon as he evacuated from campus groups, he struggled to accept that new reality.

“I would say one of the biggest things for me was — like, it never really occurred to me that something like that could happen,” Dias said. “And to come to terms with the fact that it did was something that was difficult for myself, but at the same time was also very difficult for a lot of my peers.”

Less than 12 hours after the shooting, Dias returned to campus as a student reporter for the UNLV student newspaper, The Scarlet and Gray, to document and share what happened to his campus community. While out reporting, Dias remembered seeing a police car drive past him, and the sound of sirens brought back memories of the day of the shooting.

“And I remember just like looking at the sirens, wailing by, and it just kind of just triggered something in your head,” Dias said. “You start hearing everything from that day again, start hearing the screaming, the shots — it all starts replaying in your head.”

Dias took a week off from work and coped with his emotions by talking to his friends, focusing on hobbies and going to counseling services provided by the school.

SFSU resources and prevention

At SFSU, campus departments work together to prevent and prepare for emergencies such as earthquakes, fires, smoke and active threats. The campus prevention committee includes the University Police Department, the Office of Emergency Services, Counseling & Psychological Services and the Action Care Team.

UPD is the unit responsible for immediately responding to emergencies. UPD also works closely with staff and has a campus safety plan that enforces active threat training provided by the CSU.

Apart from the university police department, SFSU also has an Office of Emergency Services responsible for coordinating services such as response, prevention and preparedness, mitigation and recovery after an emergency. The Office of Emergency Services also informs the campus community through educational campaigns.

OES and UPD intertwine their work by supporting space assessments and appraisals of safety measures in place, to secure campus safety. Hope Kaye, the OES director, acknowledged SFSU’s campus is accessible to the general public.

“We’re a very open campus,” Kaye said.“We pride ourselves on that. We’re very permeable; we’re connected to the community. We all really like that about our campus. But it’s important to also have awareness of who’s on our campus.”

In the event of a campus shooting, OES initiates a coordinated action response through the Emergency Operations Center. The EOC serves as the centralized method of communication from UPD to the campus community, facilitated by SFSU’s Emergency Notification System. Kaye encourages all students to sign up for the alerts to be well-informed before an emergency happens.

Within the EOC, there is also a medical branch ready to serve the mental health and wellness needs of students after a school shooting. The medical branch encompasses all campus resources, including Counseling & Psychological Services, Health Promotion & Wellness and Student Services.

“In the event that we had a situation like this, where we really need to stand up some robust mental health support for our community, the medical branch would take on that component of it,” Kaye said.

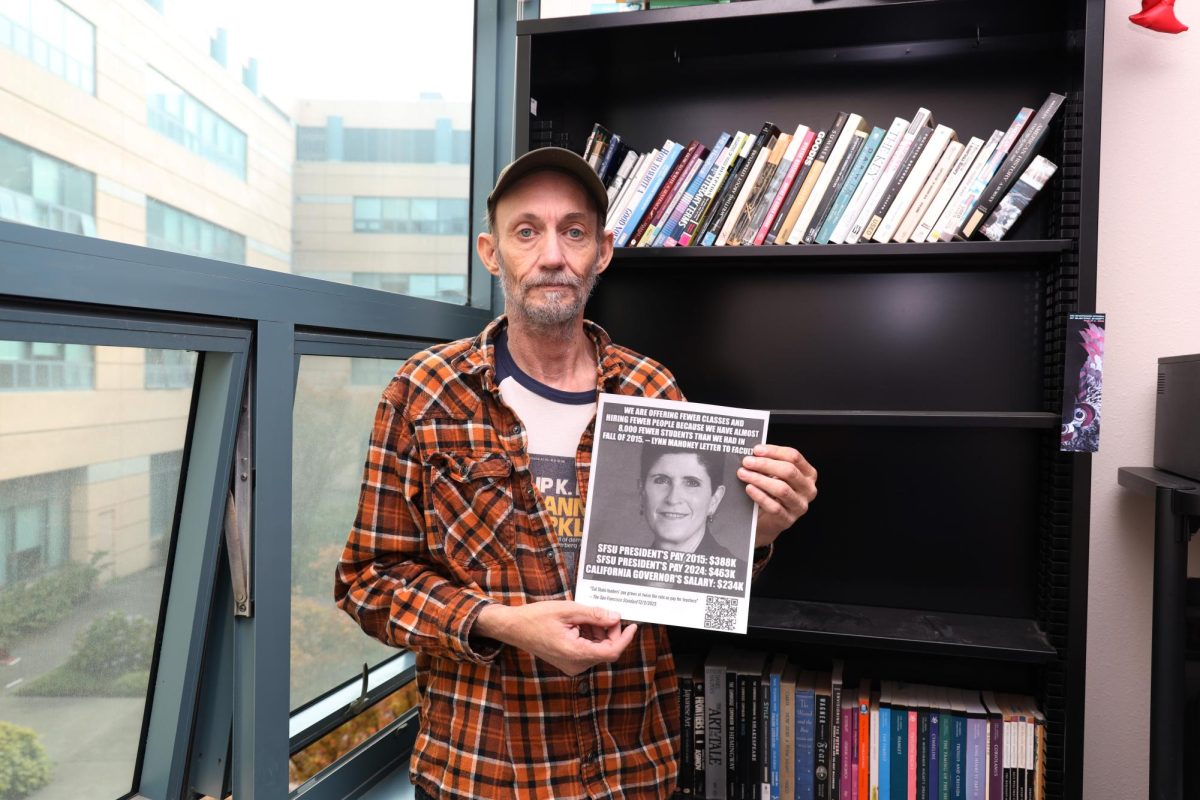

In terms of prevention, Counseling & Psychological Services (CAPS) works closely with the Action Care Team (ACT) to minimize and address student concerns involving another student’s behavior and take preventive measures for students showing signs of distress, destructive behaviors, or violence.

“It is hard to speak about particular trends in concerns, but CAPS does hear from students at times when they have safety concerns, particularly in contexts such as when there is a disruptive or argumentative classmate and when they hear of certain events on or around campus,” wrote Stephen Chen, director of CAPS, in an email. “Anecdotally, I have heard students share their overall concerns and stress of events around the country and world, and often there is mention around the frequency of school shootings.”

David Rourke, director of Residential Life and co-chair director of ACT, said the team assesses the severity of reports using a NaBITA Risk Rubric, a tool for evaluating initial mental health concerns and potential threats, and determines an action plan from there.

“But in a critical level we’re mobilizing through those two teams [UPD and CAPS] to get a better understanding of how likely is this threat to the campus community,” Rourke said. “Now, you know, I will just say, while we are collecting that information, nobody has a crystal ball around being able to predict what a student or a person is going to be able to do.”

The cycle continues

Ramirez is now a preschool teacher at Amigos de S.F. Spanish Immersion Preschool and is responsible for teaching her students safety protocols. But their young ages limit the drills the school conducts. Fire and earthquake drills are part of their educational routines, but active shooter drills are not.

All Ramirez can do is vigilantly watch over the children — without instilling fear — until the children are ready to engage in conversations surrounding gun violence.

“We should not have to be having these conversations,” Ramirez said. “But time and time again in the United States, we obviously have to, because we don’t know at any point who has a gun — who is wanting to hurt us.”