Minimal Exposure: Piecing together a broken Science Building

A Major Capital Outlay program for the infrastructure of California State Universities has put Science Building repairs and equipment replacement on their radar since at least 2006, but insufficient funding has continued to push the repairs back, adding them to a laundry list of “deferred maintenance.”

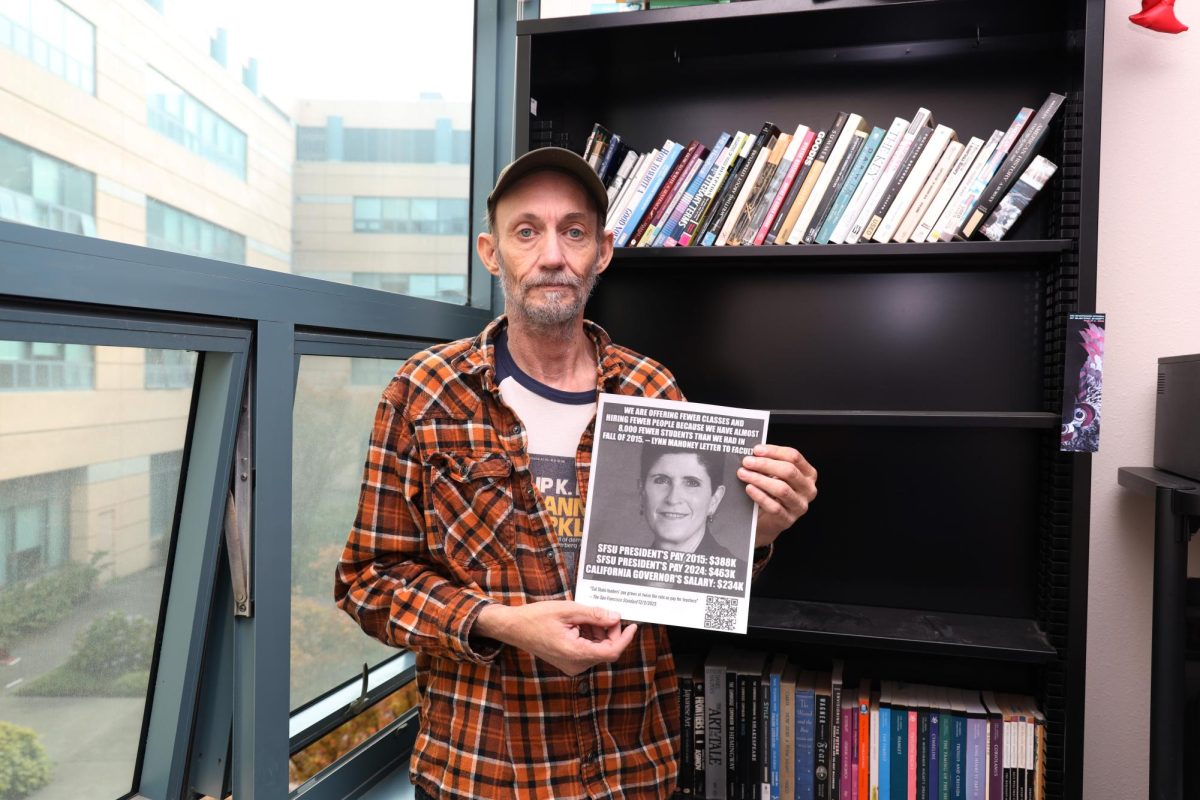

“I’d like to point out that this was not a natural disaster. The closure of the Science Building is a direct consequence of what I would call a gross negligence on the side of the University.”—Marteen Golterman, physics professor at SF State.

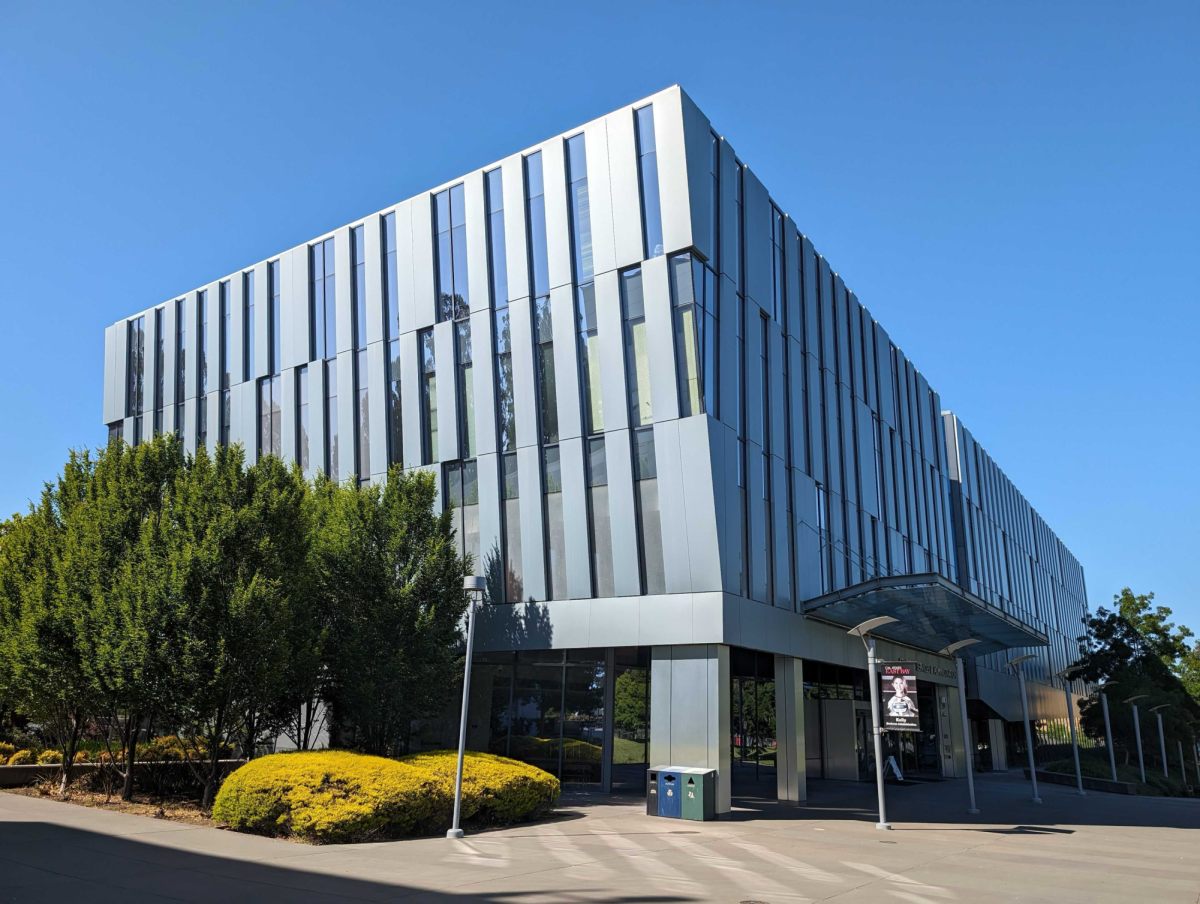

SF State President Leslie E. Wong and Chief of Staff Shawn T. Whalen said in an exclusive interview with Xpress, that officials will weigh the cost to repair the defunct Science Building against the estimated $100 to $200 million amount it would take to destroy it and create a new, state-of-the-art facility.

“If I included all the work from late December and through the remediation and the staff costs of evenings and weekends and having to reschedule 10,000 students,” said Wong. “Suddenly you get this situation where the scope of remediation in total suddenly looks like a new building.”

Though funds for the California State University system have increased in recent years, the tight budgets across campuses since the recession have resulted in postponed projects for the upkeep of buildings. Major Capital Outlay reports for the entire CSU system show that this is not isolated to SF State.

In the late 1990s, SF State worked to reduce a $66.2 million maintenance backlog from 1994, and did so with success. But by 2000, the University recorded an increased $67.3 million in work yet to be completed.

There were more than $5 million of incomplete asbestos removal projects for buildings on campus, according to a 2001 report completed by SF State for reaccreditation from the Western Association of Schools and Colleges. Asbestos remains a major factor in the closure of the Science Building, according to Whalen.

“It could be easy to dismiss SFSU’s deferred maintenance backlog by blaming it on poor leadership in the past, lack of funding, and insufficient attention to the problem,” the WASC document said.

The WASC document added that facilities on campus were often built with materials and systems secured at the lowest paid bid, without attention to their worth in SF State’s harsh climate of fog and salt.

In January, Gov. Jerry Brown proposed a 2014-15 year budget for CSUs that would provide $815 million in funds for deferred maintenance, which would lessen the current $1.8 billion amount in maintenance due across the CSU system.

Alongside expansive renovation backlogs, safety failures have negatively impacted university reviews in recent years, according to several CSU system-wide risk assessments, including the 2007 audit of Occupational Health and Safety and the 2013 Hazardous Waste Management audit.

The Office of the University Auditor recommended alongside other suggestions in the 2007 report that SF State review its Injury and Illness Prevention Program and OHS policies, health and safety inspection procedures and practices and student health and safety training.

The auditor reviewed several departments, including the chemistry department, which offered its lab for the examination of poisonous artifacts from the Science Building in 2001, but recommendations were expanded to include the entire campus, according to the report.

“We find we really don’t have the technical people to do the things that we should do on a regular basis.” —Leonard Metts, SF State technician.

Contaminants in the Science Building returned to the attention of University Health and Safety in October 2013 during an inventory of hazardous waste, required by the SF Department of Public Health according to Ron Cortez, vice president and chief financial officer of administration and finance. The process triggered a series of closures stemming from the discovery of chemicals in the Science Building’s basement photography lab.

“As they went and did their inquiry around the Science Building, and talked to the building coordinators and safety representatives they discovered a report that had taken place in the year 2000 and the year 2001. (They) had done a survey in which mercury had been found,” said Cortez. “The question by our health and safety director was: had that been remediated?”

The reports documented mercury on the first and third floors, leading the department to search there, uncover the substance again and lock the floors down.

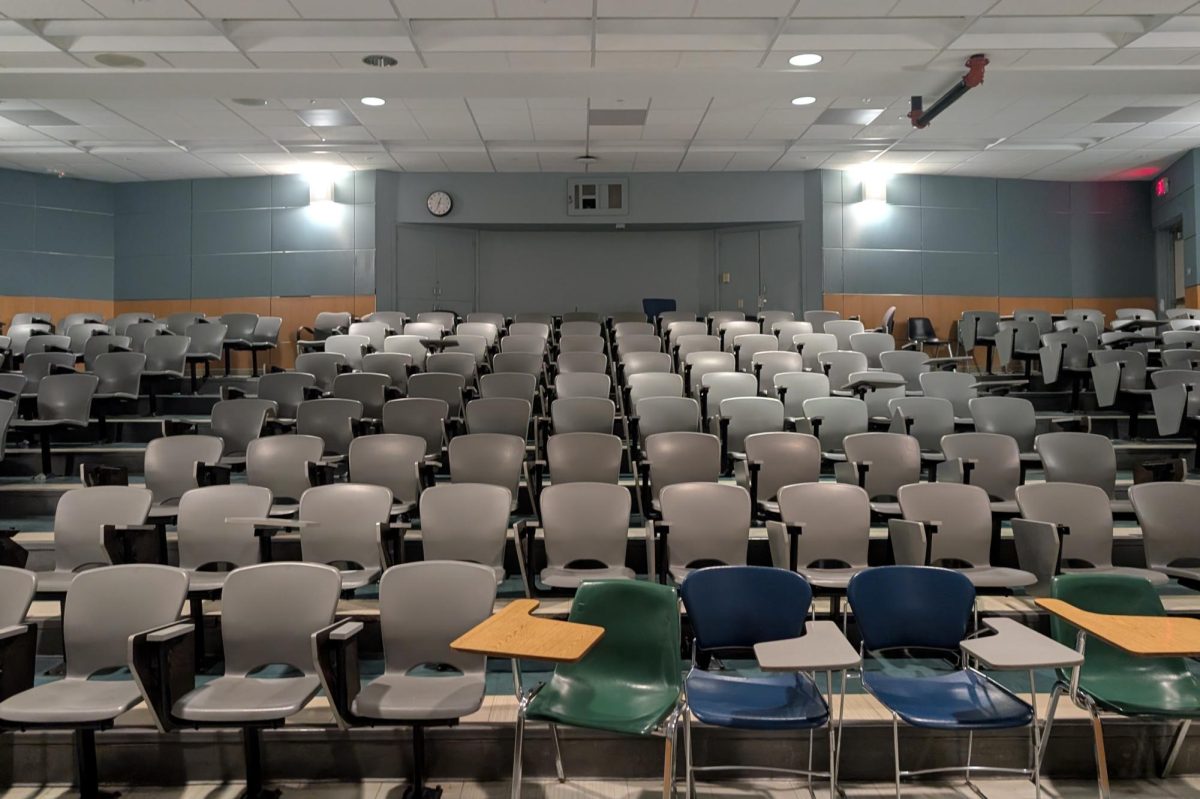

Weeks after the Jan. 10 closure, faculty and staff could be seen donning lab coats, gloves and safety glasses between Hensill Hall and the Science Building before they could venture into the building for up to 20 minutes. They were allowed to immediately remove some items, while others they could mark for testing, cleaning and eventual delivery.

The decision to allow faculty and staff into the premises came after two private consultants deemed the air quality non-hazardous, according to Wong.

Wong said that the health and safety of students, staff, and faculty were the primary cause of his executive decision to shut the doors of the building to the campus community, with asbestos and lead-based paint at the forefront of the danger.

“One of the differences here is not just that asbestos exists in the building,” said Whalen. “They found asbestos loose fibers and dust. That poses a risk that gets into the air and it’s potentially mobile if you’re starting to clean up the dust.”

In a February press conference, officials said that health risks associated with asbestos, lead and mercury for those regularly in the Science Building, were minimal.

Critics of the closure have pointed to the fact that these contaminants are common in structures the age of the Science Building, which was built in 1953.

The Gymnasium will soon receive a $2.1 million upgrade, partly because of fear that it may suffer the same fate as the Science Building, according to President Wong.

“The detection of mercury in old laboratories as well as asbestos, lead paint and mold in an older building comes as no surprise,” John Balmes, chief of the division of occupational and environmental medicine at SF General Hospital, and husband to a SF State lecturer with an office in the Science Building, said in an email to Wong.

“While it may be prudent to close the building to clean it up, there is absolutely no reason to deny faculty the opportunity to go into the building to retrieve important materials.”

“We’ve already laid out a strategy to look at the other buildings and right now my desire is to go from the oldest to the newest,” said President Wong.

In March, University officials will release long-term plans for the Science Building, according to Cortez.

“The test now is if it costs X million to remediate and X million plus a little bit to build new, then it’s an easy call,” said President Wong. “We’re going to build new.”

In 2000, Caldararo and his colleagues established a testing facility in a chemistry laboratory on campus to examine suspected pesticides on cultural items from the Hoopa Tribe of California.

The tribe had contacted SF State Professor Lee Davis after the Peabody Museum at Harvard returned regalia to them, along with a warning that they were likely contaminated with years of preservatives and pesticides.

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, or NAGPRA, of 1990 requires federally funded museums to return ceremonial artifacts to tribes.

Before they examined the Hoopa Tribe’s artifacts, the team of colleagues began preliminary testing at SF State on objects from the Treganza Anthropology Museum. The results affirmed their suspicions — the collection and the materials that touched them were riddled with not only pesticides but arsenic and mercury, according to a research paper on the results written by SF State’s Caldararo, Davis, Pete Palmer and others.

“The testing results, we gave to the tribes, and then we gave them to health and safety here,” said Caldararo. He added that the head of health and safety then apparently had the building tested and hazards mitigated.

Named after the anthropology department founder in 1968, the Treganza Anthropology Museum in Science 395 held Native American collections from archeological sites from 1996 to 1998, and again in 2000, according to NAGPRA records. During 1996, five other rooms on campus also held native artifacts.

By the late 1950s, SF State had become a storage site for archeological artifacts in California, according to a NAGPRA document. For years, the University received archeological finds like Egyptian mummies from private collections or government institutions.

Robert “Bud” Shearer directed environmental health and occupational safety at this time.

District Attorney George Gascón has since charged him with 128 felony counts surrounding botched contracts for the disposal of hazardous waste on campus, in connection with a bribery scheme involving him and an accomplice from 2002 to 2009, according to a press release from Gascón.

“One of the things that I was concerned about was that we notified the University then about our findings and then apparently there was a licensed reputable company that came in, did testing, verified that there were chemicals of various sorts in the building and the building was supposedly remediated at the time,” said Caldararo at the recent press conference. “I don’t really understand what happened with that.”

Caldararo concluded after reviewing test results from the 2013 Air and Water Sciences documents that the mercury levels in the room are the essentially the same as the levels in 2001.

Balmes confirmed, after comparing lab reports that document the museum’s contamination in 2001 and later in 2013, that mercury was present in both cases.

“We’ve been following the requirements of OSHA and we did the right thing in 2000,” said Caldararo. “It’s not anthropology that’s the problem here, it’s the lack of building maintenance.”

“The question of causation is one that is very complex,” said Whalen, noting that asbestos on pipes, artifact contamination and lead-based paint have all contributed to the Science Building closure. “It’s one that’s not forgotten but not one where we’re likely to make any conclusions.”

At a recent trustees meeting, Wong said that he wasn’t sure if the building will be able to be used again. According to his interview with Xpress, as well as CSU deferred maintenance logs, the cost of renovating the Science Building may, in the long run, be more expensive than tearing down the old structure and starting over.

Writing and Reporting: Michael Barba

Art Director: Natalie Yemenidjian

Online Editor: Nena Farrell

Editor-in-Chief: Andrew Cullen

News Editor: David Mariuz

Copy Editor: Jordan Hunter

Photo Editor: Jessica Christian

Photographer: Gavin McIntyre

Multimedia Editors: Will Carruthers and Rachel Aston