On the north side of 19th and Holloway avenues, several large graffiti pieces were buffed off of the stone wall, leaving behind blurry streaks of blue spray paint. Just across the street, two more pieces peeked out from behind the overgrown brush.

For street artists like SF State student Haidar Abu al Hasan, known by his tag, Element, expression can’t be confined to a canvas.

“Graffiti’s not really for gallery,” Element said. “It deserves to be there, but it mainly belongs to the streets.”

Element has been involved with street art for five years. He started in Kuwait, where he said the government is much more punitive when it comes to graffiti.

“You always have to be watching your back left and right,” Abu al Hasan said about street art in Kuwait.

Large cities like San Francisco and public institutions like SF State are in a constant battle against graffiti. SF State experienced this over Halloween weekend when four walls around campus were graffitied, according to the campus crime, fire and arrest log.

Chris Bennett, maintenance superintendent for SF State’s facilities and service enterprises, said vandalism involving paint, pens and etching of tags consumes between $1,600 and $1,700 in supplies and between 30 and 40 hours of work each week.

To the graffiti community, the tag is an essential part of an artist’s progression, according to Abu al Hasan, who said that artists evolve through stages of graffiti beginning with tags; throw-ups, which are quick tag stencils; burners, more intricate free-hand pieces; the wild style, an exhibition of an artist’s distinct style characterized by the classic large bubble letters, and finally murals.

“It’s about having the mind, passion and time to start your day at 12 a.m. and finish at 6 a.m. Why? To leave your name or their mark somewhere,” Abu al Hasan said.

For maintenance management specialists like Bennet, these marks have his staff working full time.

“We have graffiti removers – it’s a chemical that’s environmentally friendly,” Bennett said. “If we can’t remove it, we have to paint over it. We have to take care of it right away, or else it can get out of control.”

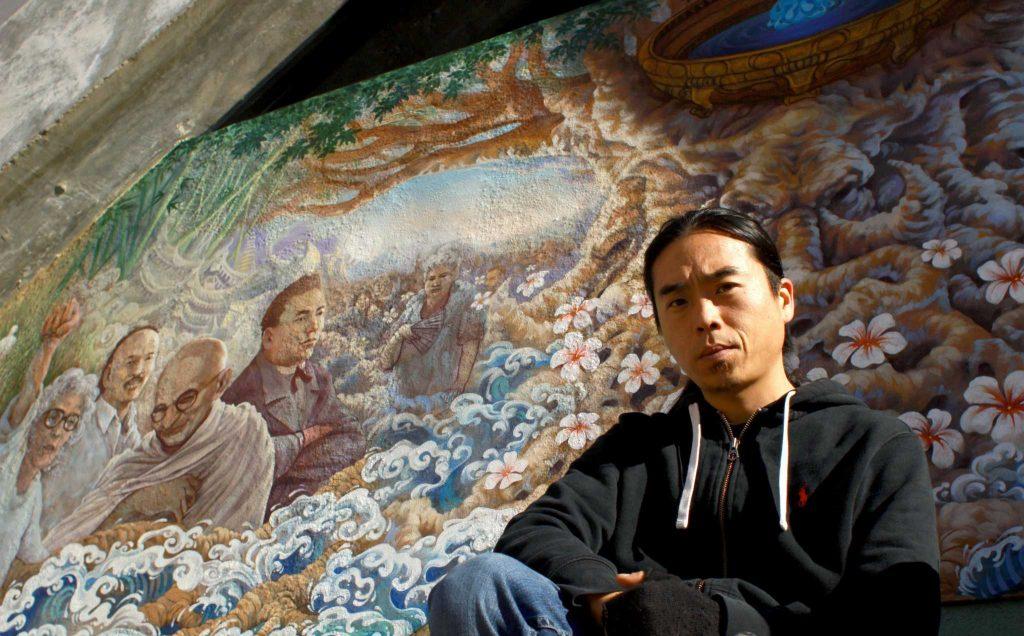

Muralist David “Hyde” Cho, who is currently restoring the Asian and Pacific Islander mural on the Cesar Chavez Center that he originally painted 13 years ago, said he is caught in the crossfires between artists and management.

The divide between art and vandalism is faint, but it does exist, according to Cho.

“There is a fine line, because part of the culture of graffiti is to vandalize,” Cho said.

Cho, 35, has an extensive portfolio of work, which includes the Santana Mural on 19th and Mission streets. In his own artistic maturation, he said he has progressed from vandalism to beautification.

“I wanted to make things beautiful rather than just destroy,” Cho said.

This kind of development is what Bennett and other officials said they would like to see.

“I have no problems with murals – there is great graffiti art – but the stuff on campus is mainly vandalism,” Bennett said.

Still, graffiti is a positive outlet for many people, according to Abu al Hasan.

“I know a lot of people have to go clean this stuff up, but that’s just part of the game,” he said. “I try to look at the bright side now. I can apply it to shirts, help with art exhibitions – besides, there’s a lot worse things I could be doing.”