Interactive graphic by Nicole Ortega

History is packed with stories of the oppressed, taking actions against oppressors in order to gain freedom and equality, and SF State played significant roles in these battles– most notably in 1968. This timeline shows not only cultural events from around the nation, but also from SF State campus.

Correction: the print version of this article said the “liberation front” began the protest that led to a strike on Nov. 6. This has been corrected online to the BSU and the Third World Libertaion Front.

Social movements are packed with nuances, but one characteristic remains the same: the oppressed takes action to demand change. In that way, the 1968 strike at SF State achieved lasting success. The impact of that movement continues to be felt today.

During the 1960s, the U.S. was home to a social revolution that questioned a long-established social, economic and racial hierarchy in the country. The Civil Rights Movement not only achieved recognition for black people in the U.S. as citizens but also paved the way for inclusion of other ethnicities within SF State and across the country.

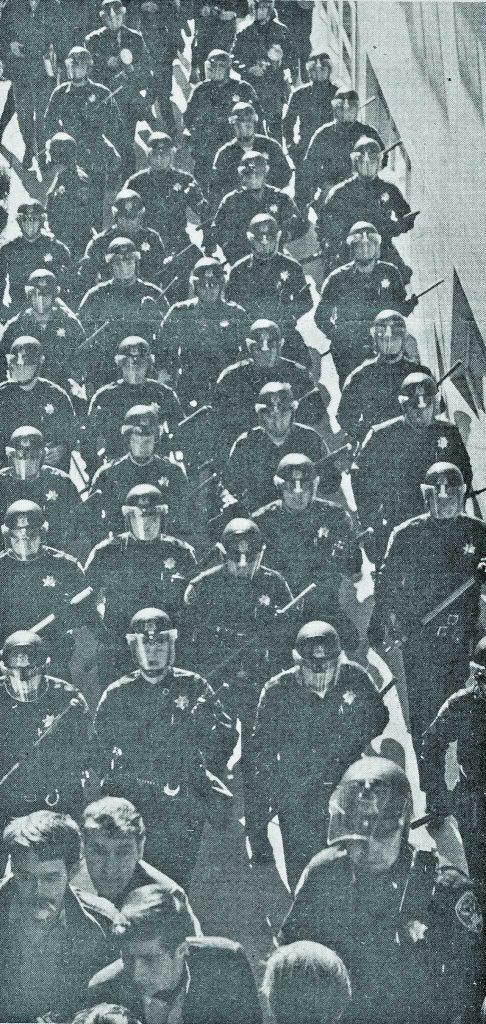

In November of 1968, the Black Student Union and Black Panther Party were joined by the Third World Liberation Front, a coalition of organizations representing minority groups in a protest that lasted five months in which they demanded a more diverse representation and historical accuracy in the academia.

“We would not longer put up with this racist country living off the poor people in the world,” the New York Times quoted Stokely Carmichael, then the Black Panther Party prime minister, during the first speech of the strike the evening of Nov. 6, 1968.

The same day, but one year earlier, about 15 BSU students showed up at the newsroom of The Gater, the school newspaper, and attacked the editor-in-chief in his office and vandalized the newsroom, according to The New York Times article. The attack was in response to a Gater editorial suggesting the college cease funds to certain groups, including the BSU.

This violent incident marked the tone for 1968. Using guerrilla tactics to bring the systematic order to collapse, the BSU sent small groups of students to different classrooms to elaborate on reasons for the strike while questioning students and faculty for not joining the cause.

Student protesters held meetings in the center of campus, while other students would vandalize department offices. The goal was to challenge the system that had oppressed them for so long.

Patty Wood, a student who studied U.S. History and American Studies at SF State in 1968, was 21-years-old when BSU showed up and interrupted one of her afternoon classes.

She remembers when the BSU took over the classroom and commanded the professor and students to leave. The 1968 strike was a time of anger and certain places on campus were unsafe, according to Wood. Classes were disrupted and lectures needed to be held at professors’ houses due to the disruptive campus climate.

Despite campus unrest, Wood believes the movement played a vital role in bringing about awareness of the existent social and cultural disparity.

“I was sort of oblivious until someone pointed it out,” Wood said. “We didn’t have a Chinese or a black professor.”

Laureen Chew, an Asian American Studies professor at SF State, was one of the students that decided to get involved during the strike. Chew joined the Intercollegiate Chinese for Social Action to protest against historical misrepresentation in a movement that led to the establishment of the College of Ethnic Studies at SF State.

“The Civil Rights Movements had been going on, the anti-war movement was happening, the Free Speech Movement was happening,” said Chew said in regards to the sentiment among Americans in the ‘60s.

After years of discrimination against her Chinese American culture and appearance, Chew learned she was not alone. She attended an informational meeting at SF State with African American, Latin American and Native American students and found that others felt the same way she did.

“I didn’t know anything about ethnicity,” Chen said. After that meeting, she conceded how little she knew about the Chinese American community, despite living within it her entire life. She also realized that her lack of knowledge regarding her own ethnicity had to do with the lack of diverse education within the school system.

Chew said that in order to understand the motivation behind joining the 1968 strike, it is necessary to acknowledge how unfair, unequal, and how exclusionary the social system was toward people that were not part of the dominant race.

Under the pressure of constant struggle and oppression, members of marginalized communities often turn against each other, according to Chew.

“It creates an interesting dilemma,” Chew said. “You have to fight the power structure within your own community to get something, as well as to fight against the outside power structure.”

Those involved in the 1968 strike were determined to incite changes in the educational curriculum, to be more inclusive of different ethnic groups and acknowledge their contributions to American history.

Strikers held activities around campus, encouraged the shutdown of the school by persuading students to not attend classes and to get involved in groups within their communities.

“Their history of struggle, survival, their poems, their songs. All that richness, we wanted to make sure it’d get established,” Chew said. “We didn’t have any of that written at that point, but it is a place where you begin, so you are no longer invisible and treated unfairly.”

Wood recalled another rally on Dec. 2, 1968. Students who were striking took over 19th Avenue with a sound truck asking students to support them and not attend class. Former SF State President S.I. Hayakawa climbed on top of the truck to disconnect the wires and commanded students to stop the disruption.

The movement was not only intended to recognize that ethnicities needed to be represented on campus, but also to address that college students needed to be responsive to the needs of their community.

The 1968 strike at SF State was the first student-led strike in the U.S. and paved the way for educational institutions around the country to challenge the lack of ethnic diversity and inclusiveness in curriculum.

Hayakawa prohibited rallies on campus and warned students they would be arrested for participating. Student strikers responded shortly after with a rally attended by thousands, according to Chew.

“I said, ‘I have the freedom of expression, I have freedom of speech, and I also feel very strongly that this is something that needs to be done in order for the system to change.”

She spent 21 days in jail for protesting and still went on to graduate from SF State within the same month.

Asian American Studies Professor Daniel Gonzalez also participated during the strike.

“My generation, the baby boomers generation, was raised, for the most part, while the barriers of racism were still high,” Gonzalez said. “But, then, as adolescents, the promise of change also came.”

Gonzalez said it was widely believed among people of color that the best route was to acculturate and assimilate into the American society, “American” being white American culture.

By assimilating, Gonzalez pointed out that ethnic minorities could enjoy “some level of freedom from prosecution and persecution.”

“For some groups, I think that was more possible than for others,” Gonzalez said.

Gonzalez said the media often paints San Francisco in the 1960s as a hippie city with drugs, poetry and writings challenging morality, which is true. However, the media didn’t accurately portray the political aspect of what was happening at SF State.

Gonzalez said that while the BSU started the strike, the TWLF and the Student for a Democratic Society organization were also key players. They had weekly meetings and set techniques, long-term strategies and demonstrations.

“The strike was clearly and logically an outcome of oppression,” Gonzalez said.

Minorities have since gained a higher level of visibility in media, television and on the internet, which Gonzalez believes has created resentment by the dominant culture. Minorities are now targeted because they are too successful, according to Gonzalez.

Chew said it is interesting how the same disagreements regarding banning immigrants from the U.S. today relate to the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882.

“It is the same thing they are saying about Latinos, especially from Mexico, ‘they are taking our jobs, they work for so cheap, they are bringing in disease, they are bringing their food and making us sick,’ ” Chew said.

Wood said she is nervous about the political climate the country is experiencing today, and referenced the recent riot at UC Berkeley in response to Breitbart editor Milo Yiannopoulos.

“Right now, I think, everything is an uproar,” Wood said.

Gonzalez said that in the 1960s, student organizations at colleges were based on political goals, and points out that today’s campus organizations do not seem to engage with social issues in the same way.

Within 50 years, many things have changed, according to Chew. From not having classes about different ethnicities, to having a department of ethnic studies is a big deal. From not having many written pieces, now there are hundreds telling the story of the diverse ethnic groups in the country.

“Protest and dissent are not meant to (not be) disruptive. Otherwise, no one is going to pay attention to you,” Chew said.