The NFL has proven itself to be a hard-hitting sport both on and off the field. Just as viewers have become accustomed to the innate aggression of the game, they have also become all-too complacent with the frequency of sexual assault and domestic violence allegations brought against the league’s players.

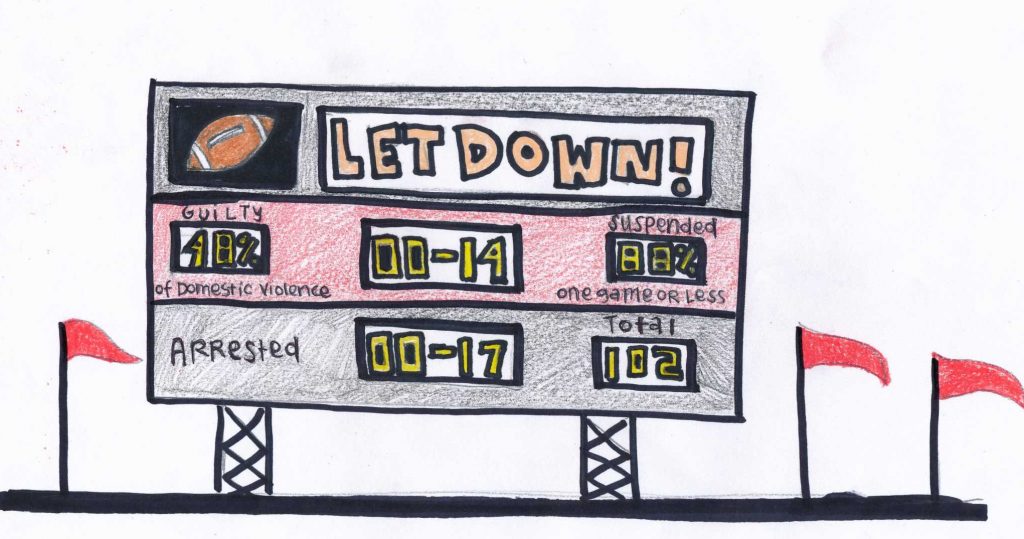

In 2014, the relative NFL arrest rate for domestic violence was 55.4 percent while sexual offenses were 38.2 percent. Between 2000 and 2015 93 players were accused of domestic violence and 10 were accused of sexual assault.

The recent NFL draft saw a continuation of this unfortunate trend as the Oakland Raiders and the Cincinnati Bengals both took a chance on players with a history of assault against women.

The Raider’s first-round pick, Gareon Conley, was recently accused of sexual assault just days before the start of the draft. Though charges have not yet been filed and the investigation is still pending, NFL spokesperson Brian McCarthy revealed Tuesday that Conley will not face any discipline from the NFL because the incident in question happened prior to the actual draft.

Essentially, the NFL did what it does best and washed its hands of any responsibility, viewing their post-draft world through rose-colored glasses.

“If they don’t see it impacting their bottom line, they’re a very conservative organization and they’re going to move on these issues kind of slowly,” said SF State race, sports and society lecturer Larry Salomon. ”But they’ll make it look like they’re doing something, which is the NFL’s expertise.”

The fact that the Raiders would even consider picking up Conley with no definite answers regarding his alleged assault is deplorable, irresponsible and frankly not surprising. After all, it is the NFL.

The Bengal’s second-round pick, Joe Mixon, has a documented incident of violence. Last year a video of Mixon punching a female who shoved him emerged. Though Mixon had been accused of this in 2014, the video gave undeniable evidence and caused the incident to resurface.

Lucky for Mixon, the NFL is extremely forgiving to those they consider a stud running back with a mean stiff arm. Mixon gave a public apology in February for what he called a “mistake” and now, three months later, he is an official NFL player.

Although the recent draft of both Conley and Mixon may seem like just a drop in the bucket of horrible choices made by the NFL and it’s players, it is also the perfect timing to shine a light on the fact that this billion-dollar industry is unconsciously normalizing violence and abuse against women.

In January the U.S. inaugurated a president accused of various accounts of sexual assault and who has publicly made sexist and degrading comments toward women. Now, nearly halfway through the year, the NFL is following suit by publicly accepting men accused of the same crimes.

Children look up to these athletes as role models, as players and people they aspire to be. What message is being sent as they grow older and learn that some of their childhood heroes have committed violent crimes against women with little to no consequences because they are professional athletes?

I am in no way saying that all NFL players should bear the burden of crimes committed by some players, but the league does hold the responsibility to make decisions based not only on skill, but on character.

This pattern of turning a blind eye or making excuses for these violent crimes against women can no longer be chalked up to the NFL simply being clueless. The statistics are clear and the media attention is real, but the solution is less obvious.

Salomon said one of the problems lies in the NFL’s hesitancy to change their policies regarding these crimes.

“If there is another scandal and if Joe Mixon does something again, they’ll trot out their PR team rather than change any policies,” Salomon said.

Curbing how these players are treated and what they are allowed to get away with at a collegiate level may be the solution to paving the way for change at the professional level.

In February, the Big 12 Conference imposed a multi-million dollar sanction on Baylor University, withholding a quarter of the college’s revenue after more fuel was added to the flames of its football team’s ongoing sexual assault scandal.

This action from the board of directors marked a step in the right direction from the conference and the NCAA to hold universities accountable for behavior of their athletes.

“A lot of universities for years did what Baylor did, try to get rid of the problem from an image point of view, sweep it under the rug, pay people off,” Salomon said. “But what are they really doing to implement policies?”

Shortly after this decision, Indiana University announced their athletic department’s decision to implement a new policy, banning any prospective athletes with a history of domestic violence or sexual abuse from entering their program. Hopefully this move will inspire other colleges, especially those with strong athletic departments, to follow suit.

Until then, the Raiders seem confident that the pending charges against Conley won’t hold true. But where there’s smoke, there’s fire. I am a firm believer in the presumption of innocence, but in a league where this type of behavior is as common as the Patriots appearing in the Super Bowl, something’s got to give.

“I think the NFL does sometimes feel like they’re untouchable,” Salomon said. “They do take these PR hits, but they survive it.”

Those left struggling to survive are the victims of these crimes, those that don’t have the fame and fortune of the NFL to support them, those who suffer the shame and mental impact of the crime committed against them.

There has to be a moment where an organization as powerful as the NFL makes a moral decision to invest even half the amount of care they put into recruiting skilled players into recruiting good people. It may cost a player years of blood, sweat and tears to be good enough to play for the NFL, but it costs absolutely nothing to be a good person.