Since he was a kid, Shea Bilé says he has lived in a mystic world. Growing up in a haunted house, being exposed to disembodied voices, incidents of dreams, flickering lights, visits from his late great grandfather that brought the spontaneous smell of fresh cut roses.

“My mother was pretty mystical. She was a self-proclaimed medium of sorts who talked often about my past lives and spirits who have passed so I grew up with that around me,” Bilé said.

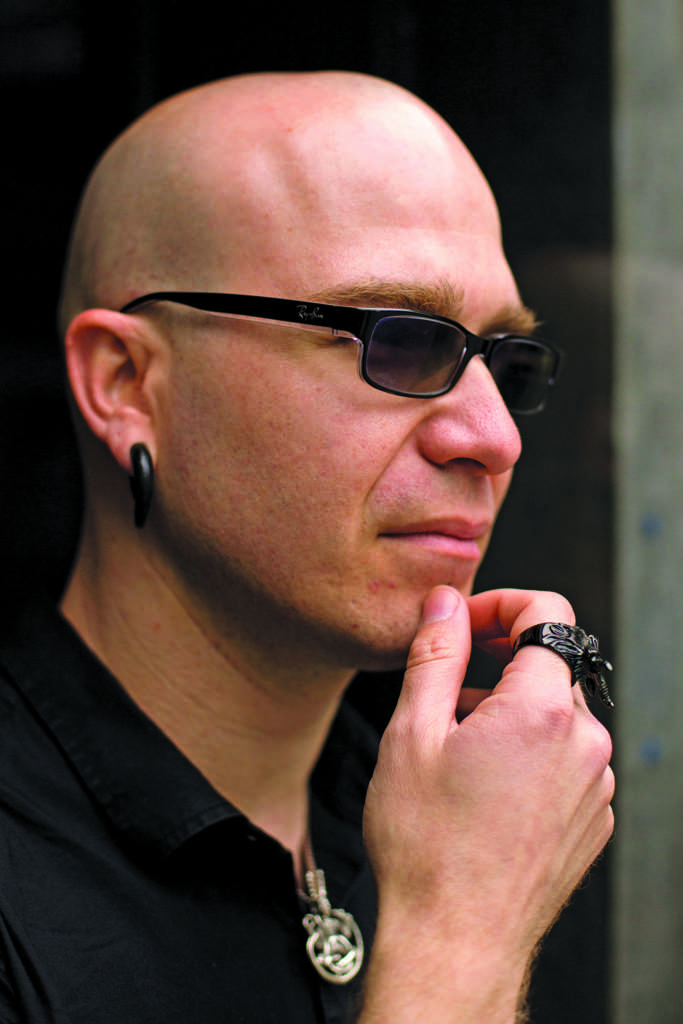

Bilé, who is now getting his Bachelor’s in both Philosophy and Religion, with a Religious studies minor at SF State, says all of us have natural predispositions in the world.

“We realize at a young age that we all have a type of wonder in the world around us and some of us are more receptive to influences we can have on our environments,” said Bilé.

Aside from an early exposure to magic from family, Bilé attributed his turn to the Occult at such an early age to an unconventional and interpersonally difficult upbringing.

The term occult, most easily be understood as “knowledge of the hidden,” includes but is not limited to practices such as Wicca, Satanism, and Paganism that utilize different forms of magic and divination.

“I was often made to feel when I was younger that I didn’t have a place to find peace, that I was disempowered,” he said about his hardest days. “When I first started looking into the Occult, I was like this is a way that I can empower myself, where I can use magic to change my environment, a way that I can fight against these people who were making my life abusive. This is a way to fight back.”

Bilé gravitated toward the idea of having a system, something to believe in. He knew early on, it wouldn’t be mainstream. He didn’t turn to Satanism at first and instead explored Wicca. He began the search for empowerment there.

Wiccans, also known as people who utilize witchcraft or identify as witches, have ancient roots in countless numbers of religions around the world. Wicca, in simple terms, can be described as a practice that is nature-oriented, has a strong emphasis on magic, manipulating one’s surroundings. Those who practice witchcraft seek to balance what they take from the world because they believe they are much smaller than the forces of nature.

Bilé quickly fell out of Wicca at around age 12 or 13 when he found some fundamental issues with some of the core doctrines –– specifically the law of three.

This doctrine states that any energy you send out comes back times three. Bilé saw this as a threat to his newly empowered self. He often questioned why forces in the world seemingly sought out to take his power away.

“My reason for going to the Occult was to be able to fight back. But here I had a religion [Wicca] telling me that if I defended myself, I’d be hurt for it,” said Bilé “That was just another way of an authority to disempower me in what i thought was a world turned against me.”

Today, Bilé identifies as a Satanist first, an Occultist second. When asked how long he has been practicing, he laughed, saying he doesn’t want to age himself too much but ultimately has been a Satanist longer than he hasn’t, having been involved for 19 years.

Satanism is often misunderstood or ill-represented as Bilé is all too familiar with. He cites the internet as one of the main sources to begin to understand the differences between these variations.

John H., a 27-year-old native San Franciscan who asked to only be identified by his first name, began researching Satanism online a few years ago when he decided he too was ready to explore religion.

“I believe you should know your options completely before you choose a religion,” John says. He originally looked into LaVeyan Satanism but quickly found it was too self-centered for him to fully identify with.

“Satanism, overall I think, has the tendency to come off as selfish because you are putting yourself above other people and thinking of yourself first,” he explains.

There are in fact dozens of variations of Satanism rather than one set path. Bilé identified with LaVeyan Satanism as a teenager, but today he considers himself a Traditional Satanist.

He recognizes Satan as a tangible, living force that he worships. Additionally, he also identifies as a polytheistic pagan, who worships a variety of gods, spirits and entities.

Bilé recalled his first experience opening the Satanic Rituals by Anton LaVey as a mesmerizing experience.

“I saw this famous line in the beginning that says, ‘on the altar of the devil, up is down, pleasure is pain, darkness is light, slavery is freedom, and madness is sanity.’ Essentially that I don’t have to live by other people’s rules,” said Bilé.

It was this line that resonated with Bilé the most.

“I realized through Satanism that I can by my own god, my own redeemer. No one is going to save me except myself. There is a lot of power in knowing that.”

He practices a variety of rituals in his own personal life, including daily meditation and prayer, intentional magic, sympathetic magic, spirit conjuration. He also is active in the SF community, often participating in group rituals.

Bilé had always wanted to live in San Francisco, but his move here in part was expedited by the city’s rich history of the Occult. The Richmond District is considered the unofficial birthplace of Modern Satanism.

“When I first came to San Francisco, I understood it to be a place of counterculture and the birth of rebellion,” Bilé said. “It was a place of religious and spiritual exploration. More specifically, the Church of LaVey, the Church of Satan.”

However, Bilé has had some trouble coming to terms with the on-campus climate, especially when it comes to acceptance of his beliefs. What he has come to find, is that campus almost exclusively caters to mainstream religious groups.

“I came here assuming that SF State would be the center of exploration,” he says. “But when I was looking at clubs, for where to participate, I found that university culture did not have a single club that represented New Age, Pagan, the Occult, or Satanism.”

He continued on to say, “This was the focal point of not only my study, my lifestyle, the foundation of which I have built my entire identity, and there was no safe place to express that.”

Because of this, Bilé decided to team up with Jacob McAdam, who founded SF State’s most diverse religious group, the Occult Club.

McAdam, a Pagan who identifies strongly with nature and its forces, immediately connected with Bilé. because as he was posting flyers to start his own Occult club, he realized someone else was posting fliers of the same concept.

“I thought to myself, I really need to find this guy. So I emailed him and we sort of came together to lay out the idea for club,” said Bilé. “That it would be a space for all these religious minorities to come together, have a space to freely exchange ideas.”

The club has existed on campus for over a year now with a revolving membership of 50-60 members. The duo describe the organization as a success.

McAdam said the meetings are a mixture of education and providing a service to people. Each week, the club meets in the library and a different member introduces a concept or practice to the group that gives insight to a part of their individual practice.

“We have had people teach recently about the importance of dreams, the significance of animals in nature to conjuring spirits even,” McAdam says of the workshops. “We also participate in group rituals around certain holidays.”

Other topics in the past have included sigil magic, spirit conjuration, healing, curses, divination and astral projection.

A mutual frustration the co-founders of the club share is the inability of the organization to become a registered club. As set out by the University, all groups must have an adviser sign on — whether it be a professor or member of faculty to ensure that the club has guidance, can manage funds and can be held accountable.

Bilé and McAdam estimate they have met with 25-30 professors since the organization started, and yet no faculty member has been able to make them an official club. Reasons they were given by the faculty range from just a lack of understanding about the club to being outright nervous to be accountable for it.

Becoming a registered club opens many doors that they would like to take advantage of, such as a designated meeting space, access to funds to host guest speakers, access to equipment, ability to table, being featured on the school’s website.

The two describe the process as thoroughly frustrating and for Bilé, he sees it as an innate form of discrimination, even though he recognizes the administration’s attempts to extend the deadline for finding an adviser.

“Every other club gets to do these things,” he says. “We may be the most diverse religious organization on campus in what is supposed to be one of the most tolerant spaces, and we still can’t get a member of faculty to sign us on. I can’t help but think that in itself is a form of discrimination.”

In addition to being formally recognized, Bilé points out how necessary the service the Occult club provides is for campus culture.

“There are people abusing the system to throw pizza parties,” he says. “We have a legitimate service we are giving to people who are already marginalized, discriminated against, coming from families who may not accept them. And then they get hit with this.”

He expresses his frustration further, “I feel that if it’s trouble for us to get recognized, in some way it substantiates the marginalization in a passive sense.”

Bilé was hoping that he would accredit the club before he graduates this May. The reality of this is becoming bleaker over time.

“I don’t blame anyone for this. It’s a big topic and not many people are educated about it. So I empathize with the staff who can’t sign on,” he says. “But we have to represent everyone. What is the alternative? The fact that we all come together in one space, from such different paths is unheard of outside campus. It would never happen. That is what makes the Occult club so special and incredibly important.”

And as for Satanism itself, Bilé says he owes everything to this path. “Now I can find my own source of empowerment, a beauty within myself. Find a way to express myself in a healthy way. I no longer have to accept these assessments of who I am. And in many ways Satanism saved me. In ways that other paths couldn’t or weren’t offered to me.”