On April 19, 2018, a student-led protest in Nicaragua quickly escalated into a national rebellion demanding that President Daniel Ortega and his wife and Vice President Rosario Murillo step down.

Six months later, the uprising turned deadly with 317 people killed according to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, and neither side willing to back down.

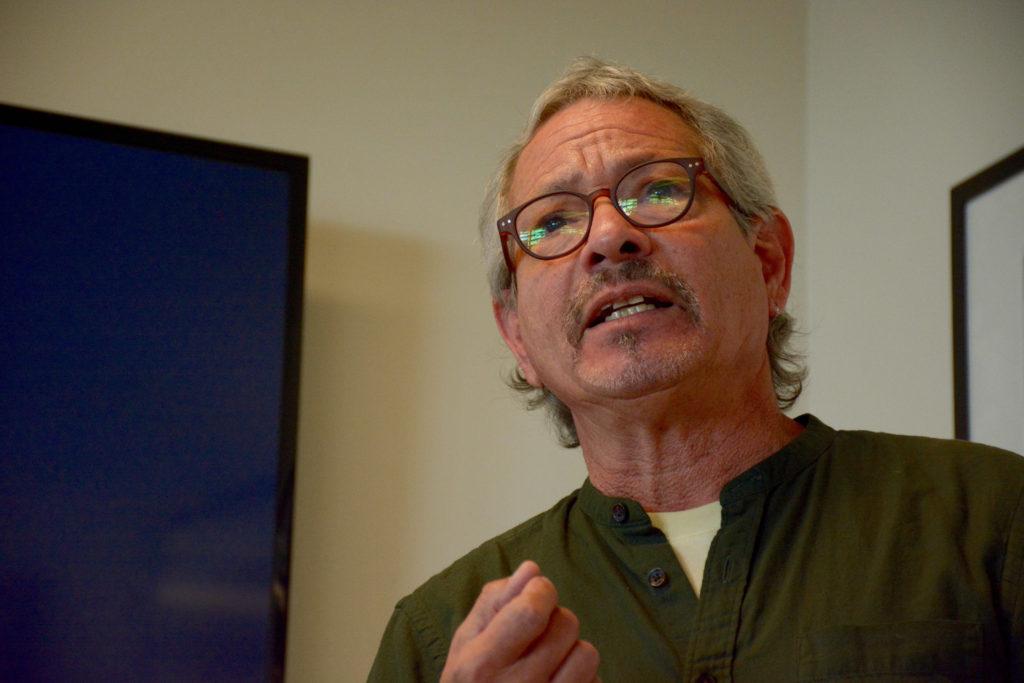

Dr. James Quesada, an SF State medical and cultural anthropology professor, discussed the Nicaraguan uprising during an Oct. 17 anthropology department lunchtime discussion with students and faculty.

Quesada, who was in Nicaragua during the uprising, described streets filled with human blockades and manned barricades. Nicaragua’s people face a crisis as government troops clear out protest camps and roadblocks.

“We have people who have been tortured and killed in prison,” Quesada said. “We have a situation where people are hiding, and friends of mine that were part of the opposition have somewhat fled the country.”

Quesada studies the psychological and social effects of the violence and conflict in Central and North America. He spent more than 25 years researching the impact of the Nicaraguan Revolution that transpired during the 1980s.

Victims of the most recent protest have included teenagers, babies, police officers and some government supporters.

“Universities shut down and the rest of the cities began to rise,” Quesada said. “It wasn’t just students, all kinds of people had enough of Ortega. They were really tired of his authoritarian ways.”

Quesada explained that the protests began after Ortega announced new taxes that would cut retirement benefits for pensioners while forcing workers and employers to put more money into the country’s pension plan.

“Because there is a revolutionary history in Nicaragua, the elders weren’t about to take it lying down,” Quesada said. “The university students rose in defense of the elders.”

Former diplomats, political analysts and a Nicaraguan youth activist held a discussion about the protests in Nicaragua on Aug. 8. During the discussion, Víctor Agustín Cuadras Andino, Nicaraguan youth leader and activist, said university students, farmers and blue-collar workers have all come together to demand democracy from the streets, as well as the country.

“What’s been happening recently in Nicaragua does not follow political lines of left or right, but rather an organic uprising from all oppressed groups,” Cuadras Andino said.

The uprising has largely gone under the radar in North America, and SF State students appreciated Quesada’s expertise on the subject.

“Professor Quesada gave us wonderful background information and we can see exactly what April 19 meant,” said Robin Rome, anthropology graduate.

Ironically, Ortega first gained leadership in the 1970s after helping to overthrow a man widely described as a dictator.

Ortega won the 1984 presidential race and took the country in a leftist direction, with a controversial program of nationalization, land reform, wealth redistribution and literacy programs.

He lost the 1996 and 2001 presidential elections, but won in 2006. Since then, he’s been unwilling to relinquish power.

“He was able to change the electoral rules in Nicaragua, so he was able to run for a third term just this last year,” Quesada said. “Last fall, he decided to make his wife vice president.”

Protesters have accused Ortega of undermining the nation’s democracy by manipulating the law, the Supreme Court, the constitution and the electoral council.

“He’s such a wonderful, calculating politician, unlike Trump, in the sense that he was able to engineer complete domination of the legislature, judiciary, of the military and the police,” Quesada said.

According to the Guardian, journalists who are critical of Ortega’s government have been targeted or threatened.

“April 19 was the straw that broke the camel’s back and has completely changed the nature and the future of Nicaragua,” Quesada said. “Who knows where it is going to go. Who knows what the fate is.”