San Francisco’s acute care hospitals have met California’s earthquake safety standards ahead of a 2020 deadline, but a second state safety requirement would cost too much for some hospitals and force them to close by 2030, according to hospital industry officials.

“Functioning hospitals are critical after major disasters,” said Dick McCarthy, executive director for the California Seismic Safety Commission. “They have to be up and running. You cannot have the hospitals be a victim too. The staff has to be safe, the hospital has to be functional.”

Aware of hospitals’ vulnerability, California legislators passed Senate Bill 1953 in 1994 and began grading its general acute care hospitals based on how well they could endure earthquakes.

Those graded “Structural Performance Category 1” (SPC-1) — at risk of collapse during a strong earthquake — could no longer provide general acute care beginning 2008. Those graded SPC-2, likely irreparable following a strong earthquake, would be prohibited from providing the same care starting 2030.

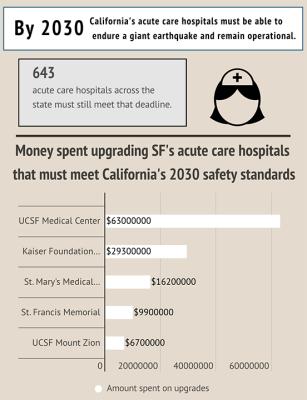

The state’s hospital industry has struggled to meet deadlines, and California granted eight extensions to push back the 2008 deadline to Jan. 1, 2020, and a few to 2022, according to the California legislature. But 643 general acute care hospital buildings across the state — 12 in San Francisco county — must still meet the 2030 deadline, according to data from the Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD).

When the Northridge Earthquake struck San Fernando Valley in 1994, it forced people to evacuate 82 medical buildings. The quake killed 61 and injured 8,700 — more than 1,600 of whom required hospitalization, according to a report by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Proponents of the legislation, such as the California Nurse’s Association (CNA), have condemned hospitals for lagging decades behind schedule. The CNA was not immediately available for comment but forwarded an August post by its executive director.

“By asking for constant extensions, hospitals are literally gambling with the lives of Californians,” CNA Executive Director Bonnie Castillo stated on Medium.

There’s a 72% chance that a magnitude 6.7 or greater earthquake will strike San Francisco between 2014 and 2043, according to a U.S. Geological Survey. Meanwhile, the state is overdue: If an earthquake happened tomorrow, it would be late.

The statewide cost to upgrade SPC 2 hospitals ranges anywhere from $34 billion to $140 billion, according to a study commissioned by the NHA and published by the nonprofit RAND Corporation think tank. With few exceptions, hospitals shoulder that price tag by themselves, according to Jan Emerson-Shea, vice president of external affairs for the California Hospitals Association (CHA).

“Whatever it is, hospitals are going to pay it, and ultimately someone has to pay the hospital. That might be an insurance company. Premiums are going to go up. The cost of care is going to go up,” Emerson-Shea said.

Meanwhile, 34% of California hospitals experience financial distress, and that could rise to more than 50% to meet the 2030 requirement, according to the RAND Corporation study.

The CHA proposed a bill to scale back the 2030 requirements to apply solely to buildings that provide an emergency department, emergency room, surgical services and recovery care. The goal, Emerson-Shea said, is to keep hospitals open and affordable while protecting the most vulnerable of patients.

“This would really focus the resources necessary on the parts of a hospital most important after a disaster, and it would really bring down the price tag,” Emerson-Shea said. “This idea that the hospital has to remain fully operational after an earthquake honestly doesn’t make sense in today’s world.”

The NHA staunchly opposes the bill, which is proposed for the state legislature in 2020.

“2020 is upon us, and 2030 is right on the horizon,” Castillo stated on Medium. “The earth doesn’t grant extensions, so California hospitals need to stop hedging bets — and go all in for seismic safety.”