Palestinian Student Experiences

Responses to Lawsuits and Timeline

The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict on Campus: Introduction

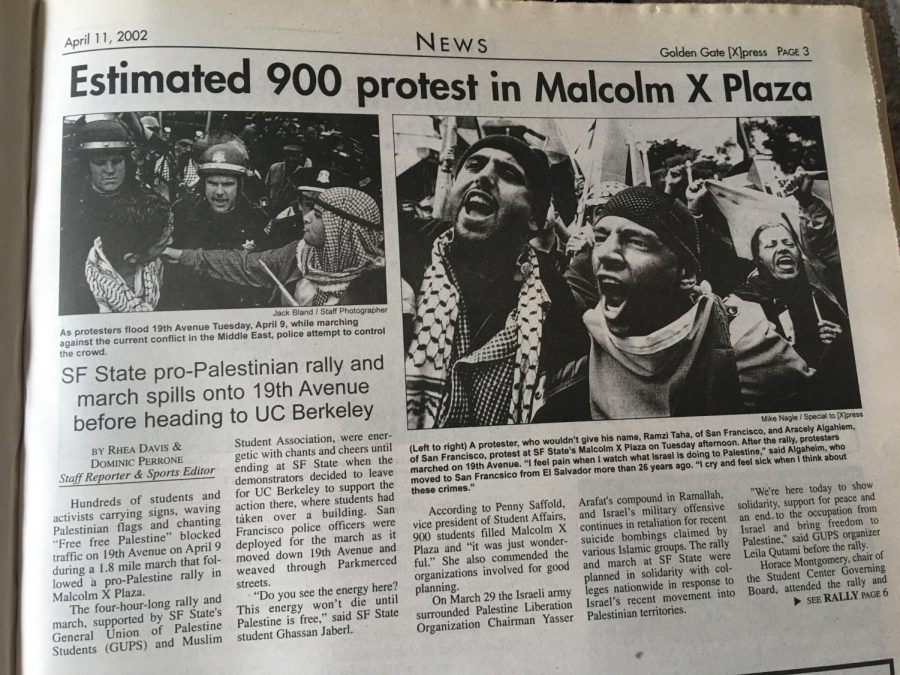

Archived campus newspapers from the ’70s and ’80s document decades of turmoil, heated protests and teach-ins by students impacted by the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. While the pages have yellowed over time, the issues remain relevant to campus today.

For SF State — known for its reputation of social justice with the first and only College of Ethnic Studies in the country created after student strikes in ’68 — decades of unresolved conflict for Jewish and Palestinian students have left those affected by this tension with different impressions of the campus’ core values.

Despite its physical distance from SF State, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has affected the university’s students, faculty and administrators. Information from over 80 interviews detailed how actions from university administration, student organizations and outside players have discouraged involved students from fully exploring and expressing their identities and values on campus.

It becomes deeply personal for students when their identities, religions or families are subject to scrutiny across the college. These tensions can evoke generational trauma for students — some are reminded of current rising antisemitism and the Holocaust, while others think about the repeated displacement and continued occupation by the Israeli government and military they and their families experience.

Secular European Jews in the 19th century sought to create a Jewish-majority country to protect against increasing antisemitism that would culminate in the Holocaust. It was important for them to return to a land that was biblically and historically significant to the Jewish people, which at the time was known internationally as Palestine and under Ottoman control before becoming a British colonial mandate.

This desire for a Jewish state was and is known as Zionism, and is still seen as important for many Jews around the world as a safe haven from antisemitism.

After Arab countries rejected a U.N. partition plan that would give less than half of the land to Palestinians — who at the time were the significant demographic majority — Israel declared independence in 1948, resulting in a war with neighboring Arab countries.

Over 700,000 Palestinians were made refugees during the 1948-49 war, as Israeli military groups massacred Palestinians, looted their homes and later moved new Jewish immigrants into the houses. Seventy-two years later, after decades of violence, attempted peace processes and multiple regional wars, Israel currently occupies the West Bank and Gaza, where most Palestinians live.

The U.S. has been heavily involved in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as a strong ally to Israel since the late ’60s. Former President Barack Obama signed a $38 billion military aid package to Israel in 2016. U.S. presidents have led attempted peace processes, along with the Trump’s administration’s recent attempts to generate normalization agreements between Israel and multiple countries.

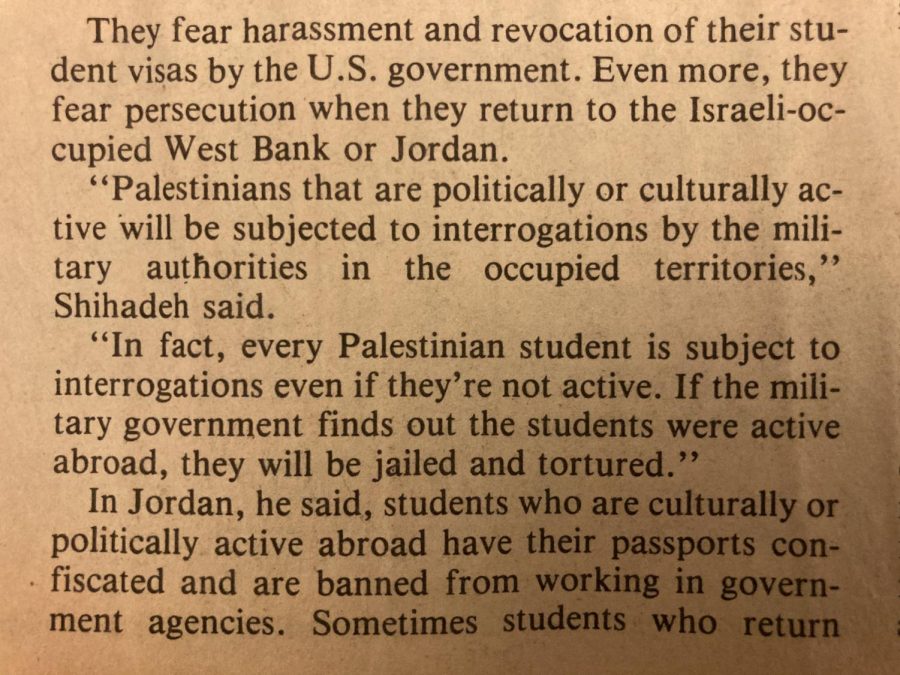

In and prior to the ’70s, students on campus feared speaking up and advocating for the rights of Palestinians because of surveillance by outside organizations and governments. Today this surveillance also takes the form of online blacklists which could threaten the future employment or education of outspoken students.

“I think for some people, it scares them away,” said Sabreen, student president of the General Union of Palestine Students. “And that’s the point of blacklisting. It’s about silencing anyone who speaks out for Palestine.”

Sabreen said that despite concerns for their safety, Palestinian students work to reclaim a narrative actively erased in America by generating awareness of Palestinian culture and the ongoing occupation of Palestinian territory.

Jewish students involved with the primary Jewish organization on campus, SF Hillel, often feel alienated from other student groups that oppose Zionism and stand in solidarity with Palestinian students. Some members of SF Hillel attribute this disconnect to what they feel is a misrepresentation of Zionism and of the Jewish community on campus, which causes some to hide their Jewish identities.

“Jews start to not feel welcome, even if they’re not Zionists,” said one Jewish student who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “I think that’s the first question that’s asked generally when the topic comes up: ‘Oh you’re Jewish, what are your views on Israel?’ And that determines how people perceive you.”

Aside from the discomfort faced by SF Hillel students, anti-Zionist Jews often fear ostracization from their own community and families because of their solidarity with and support for Palestinian students.

Despite the intensity and scope of these circumstances within the university — and universities across the country — these tensions remain invisible to many.

“There’s a lot of stakeholders in this, but the majority of our students just don’t care,” said Alondra Esquivel Garcia, former Associated Students vice president of external affairs. “I think they just don’t see the issue.”

Most students are unaware, but for some who are Palestinian, Jewish or Israeli, the situation has been described as uncomfortable and at times unsafe, as clashing narratives and experiences combine with flashpoints more than 7,000 miles away.

The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict on Campus: Jewish Student Experiences

When Ben Lieberman first came to SF State, he wanted to bridge gaps between Jewish and Palestinian students.

He introduced himself to students in the General Union of Palestine Students. However, after becoming involved with SF Hillel for a Jewish community, he felt the students from GUPS perceived him in a more negative light.

“It’s been hard,” Lieberman said. “Certain Jewish students are like, ‘Ben what the fuck.’ But then some of the Palestinian students when they see me are like, ‘Oh, you’re with them, and they’re Zionist.’”

“It’s hard because I end up engaging more with the Jewish students who disagree with me, then I get to with the Palestinian students who maybe don’t realize I do agree with them — and I want to engage with them but it’s hard,” he said.

For Jewish students who find community through SF Hillel, alienation from parts of the campus community can follow. Seeing the intensity of tensions and feeling an expectation by others to feel strongly about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has made many students avoid the issue altogether, repress their Jewish identity on campus or identify as Zionist or anti-Zionist because of the campus climate. As a result, Jewish students can struggle to find space at SF State where they can express their Jewish identity and engage in healthy discourse or learning opportunities on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Sasha Joseph, who worked at SF Hillel for four years and was the first Jewish Student Life Coordinator at SF State for the Fall 2019 semester, said Jewish students often feel bombarded by questions or assumptions about how their Jewish identity relates to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and Zionism.

“I think sometimes Jewish students just want to be Jewish, or just want to be,” Joseph said in an April interview. “They just want to wear their star of David and not be asked, ‘What are your thoughts on Israel-Palestine?’”

SF Hillel serves college students citywide, but its building is located blocks from SF State. Its staff facilitate social and educational programs and outreach activities on campus. It is meant to serve students’ religious, communal, cultural and educational needs.

SF Hillel is the only campus Jewish organization to have consistently served SF State students for decades, with documents dating back to the ’40s. It is an independent nonprofit organization, affiliated with Hillel International, the largest Jewish campus organization worldwide.

When most Jewish students come to campus, Israel is not at the front of their minds. However, after getting involved with SF Hillel or learning of the history of tensions at SF State, issues around the Israeli-Palestinian conflict can shape some students’ experiences.

Jason Steckler, SF State alum and former Israel Experience Architect at SF Hillel. “I basically went to college with not a strong background in my Jewish identity and upbringing. I’d actually heard from a friend of my mom’s after having been accepted to SF State but still graduating high school, that the campus was a hotbed for Israel-Palestine. And that it was particularly anti-Israel. At the time as a senior before college, when I heard that I didn’t care, like ‘This will have no effect on me because it’s not what I was gonna go to college for,’ to get into that conversation. Little did I know, that I dove headfirst deep within the first two years of college.”

Savannah Landau, SF State alum: “When I started here, even before I started here, my grandparents were very concerned about the antisemitism on campus. And I’m all the way from Southern California so the fact that they heard about it from there was like ‘Oh maybe that is something to look out for, but I’m still gonna pursue it.’”

Experiences differ among students because Jewish identity and heritage are diverse, and viewpoints, politics and definitions of Zionism and antisemitism vary.

Though not all Jewish students in SF Hillel identify as Zionists, those who do seek the Jewish community there often feel isolated from other student groups who are critical of Israel or oppose Zionism.

“If you’re a Jewish student, you’re kind of forced into this conversation whether you want to be a part of it or not,” SF Hillel President Ocean Noah said.

Noah said that while she doesn’t relate to Zionism the same way some students in SF Hillel do, as president she must account for their concerns.

She also said that pressure on campus to discuss or have a strong perspective about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict creates anxiety for her as a Jew of color.

“We have to think about other histories and colonization,” Noah said. “And I think that can be a very difficult conversation. Like, wow — what if my heritage is repeating some things that have been done to my other heritage? That’s very hard to think about, and I personally avoid that. It’s not fun for me.”

Opposition to Zionism and protests against Israeli violence toward Palestinians are common on campus. Other historical student groups show solidarity with GUPS concerning the conflict, such as Student Kouncil of Intertribal Nations, el Movimiento Estudiantil Chicanx de Aztlán, Black Student Union and the League of Filipino Students. These organizations also hold rallies for climate justice and undocumented students and stress solidarity in both international and local struggles against oppression.

SF Hillel employees and students involved with SF Hillel have said that other student groups frame SF Hillel as opposing these organizations’ goals and values, as they see Zionism and social justice as incompatible.

Gabe Smallson, student representative of SF Hillel and president of the Jewish fraternity AEPI, said that despite knowing about the tension on campus, he has only felt directly targeted by other students for being part of SF Hillel twice.

“I was just walking,” Smallson said. “And this kid is skateboarding by and yells, ‘Get the fuck out of here you fucking colonizers.’”

He said SF Hillel and AEPI have had some of their lowest membership numbers this past year. He and others speculate it is because Jewish students without a strong Jewish background or opinion on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict may not want to be openly Jewish or a part of these Jewish organizations because of what he describes as an anti-Zionist campus climate.

In November 2018, then-SF State students Jake Scheinberg and Lex De La Herrán attempted to create the campus organization American Jewish Student Activists after a white supremacist shot and killed 11 people at the Tree of Life Synagogue. Focusing on U.S. politics, the group sought to distance itself from assumptions others have of SF Hillel while providing Jewish students with a community that could build coalitions with other student organizations.

Though short-lived, the initiative represented an attempt by about a dozen students from SF Hillel to steer conversations on campus away from Israel and center their voices toward opposing antisemitism and promoting shared Jewish culture and solidarity for social justice in America.

In February 2018, a separate unofficial Jewish student group — Jews Against zionism — was created in February 2018 as a space for anti-Zionist Jews on campus.

JAz started a few months after now-graduated Savannah Landau watched a documentary in class about an Israeli teen imprisoned for refusing to join the Israeli Defense Forces.

Landau, who noted she had never interacted with Palestinians before, said she went to the GUPS office and learned about the realities of many Palestinians that she was ignorant to before.

“I think what threw off my paranoia was them knowing I was Jewish, and they’re just like, ‘Yeah.’ And this little shrug like, ‘That’s not our issue,’” Landau said, adding that despite her initial hesitation she was warmly accepted. “And finally finding out the difference I guess of Zionism and Jewish identity.”

Landau found a new community in anti-Zionist Jewish students and those she met in GUPS. She described getting frustrated whenever Jewish organizations or individuals would accuse Palestinian students and professors of antisemitism for anti-Zionist sentiments. Her frustration extended toward the college administration for investigating several of the accused.

She and another anti-Zionist Jewish student started JAz in large part to counter the conflation of anti-Zionism and with antisemitism.

“We wanted to finally be the Jewish voices that are like, [Zionism] doesn’t have to be what Jewishness looks like anymore,” Landau said, adding that creating JAz strengthened her love for her Jewish identity. “This doesn’t have to define me.”

Landau intended for JAz to be a voice for Jewish students opposing what she describes as the weaponization of antisemitism against Palestinians and anti-Zionist Jews. However, she said that since she formed the organization, it has been called a front for Palestinian students, and members have been called self-hating and ignorant. Some staff and students involved in SF Hillel have said that anti-Zionist Jews are a minority in the Jewish community and are seen as holding fringe viewpoints.

Landau said portrayals of anti-Zionist Jews as a minority in the Jewish community “further positions us as a frivolous group in the community and erases the violence that Zionism causes Palestinians and other marginalized groups, globally.” She said Jewish students were still fearful of joining JAz because they, like her, could be labeled antisemitic or a traitorous and self-hating Jew.

“I was afraid of being exiled by my family,” Landau said.

An Israeli-American student who spoke on the condition of anonymity shared similar fears.

The student said they originally felt discomfort seeing anti-Zionism and protests of Israel on campus, perceiving messages denouncing Zionism as inherently antisemitic. When they first came to campus four years ago, they didn’t know or care what the Palestinian flag looked like. It took talking to Palestinians on and off campus to begin understanding a narrative that the student had ignored and seen distorted in Jewish-American communities — and systemically erased in Israel.

“When you are Israeli, and you start off as a Zionist and you change or shift, it’s very emotional,” the student said. “It’s not easy for me. It makes me question a lot of things, and it could strain the relationships between you and your family. And I think that’s why people don’t want to.”

The student said that as they listened to the stories of Palestinians and connected with them over their years at SF State, their viewpoints changed. Though they want to attend a GUPS meeting, the student wouldn’t because their parents would be extremely unaccepting.

Though the student said they never experienced antisemitism on campus, they are currently uninvolved with Jewish and Palestinian campus organizations and don’t often tell people they are Israeli.

However, a body of students feels threatened and unwelcome by anti-Zionist sentiments expressed on campus that they say veer into antisemitism.

Some students said anti-Zionist protesters use critiques of Israel to target their Jewish identity or assume their views on Israel because they are Jewish or part of SF Hillel. Others consider their connection to Israel to be an intrinsic part of their Jewish identity.

“I feel that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict has created this image, this really ugly caricature of what a Jewish student is on campus,” Noah said. “And it’s someone that is maybe greedy or privileged to the point where you’re spoiled or called a colonizer or someone who wants to erase Palestinians.”

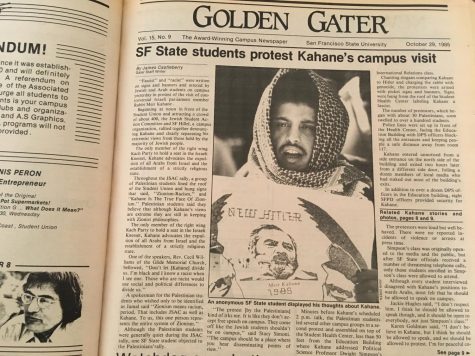

In 1985, right-wing and anti-Arab Israeli politician Meir Kahane, who advocated for the expulsion of all Palestinians living in Israel, was set to speak at an international relations class at SF State. The Jewish Student Action Committee condemned Kahane’s views and protested his visit, saying he did not represent most Zionists. GUPS, allied organizations and anti-Zionist Jews protested Kahane’s visit separately, stating that Kahane exemplified all forms of Zionism — including the beliefs of Zionist students in JSAC.

The sentiments expressed during the protests and letters to the school newspaper such as “Kahane, you are not welcome on this campus,” made some Jewish students, including those who opposed his visit, feel uncomfortable and unwanted on campus.

“It’s like they [Palestinian students] don’t accept free speech on campus,” Stacy Simoni was quoted saying in the Golden Gater in 1985. “They come off like the Jewish students shouldn’t be on campus.”

Jewish students said almost the exact same words in 2016, after student groups came together to protest then-Jerusalem Mayor Nir Barkat speaking at an event hosted by SF Hillel. Protesters wrote in a statement that Barkat enforced exclusionary policies and practices against Palestinians when he was mayor. Among the protesters were Jewish and other non-Palestinian students.

Some SF Hillel students attended to question Barkat’s policies. But amid the protestors shouting, “Get the fuck off our campus,” they felt a greater need to defend the event.

Students present filed complaints to the university, stating the administration unfairly handled the protest. A year later, the Barkat event became a centerpiece in a lawsuit against the university alleging institutional antisemitism. This lawsuit was dismissed with leave to amend twice in federal court before being dismissed with prejudice, though the university settled a similar lawsuit filed in state court.

Three SF Hillel students recently reminded the administration of some of the terms of the settlement in an open letter to President Lynn Mahoney, writing, “Our university made a commitment to address the systemic antisemitism and anti-Zionism on our campus.”

One of the students who signed the open letter was Zachary Weinstein, president of the Israel-centered student organization I-Team. Weinstein became involved with SF Hillel and I-Team over a year earlier after seeing a protest on campus. The protest was in response to Provost Jennifer Summit sending out a university memo listing Israeli Independence Day as a religious holiday, and not including Ramadan and Eid Al-Fitr — later said to be an error by Summit.

He recalled protesters chanting, “Causing pain since ’48.”

Protestors were referring to the expulsion and massacres of Palestinians in 1948 that is known as the Nakba — an Arabic word for catastrophe. Weinstein interpreted their protest and subsequent chants of “Zionism has got to go” as an attack on Israel’s right to exist.

“They were against Israel’s existence, not just current government policies,” he said. “That is what scared me, so I got active with Hillel.”

Weinstein has stood out as a vocal advocate for Jewish, Israeli and pro-Israel students. However, many Jewish students who see these tensions or feel discomfort over depictions of Israel and Zionism disconnect from the Jewish campus community or disengage from campus issues entirely.

This more common experience of American-Jewish students feeling both safe and uninvolved is illustrated in a report conducted by students in the doctoral concentration in Education and Jewish Studies at Stanford’s Graduate School of Education, “Safe and on the Sidelines.” It included interviews from 66 Jewish students on California college campuses — including SF State — who weren’t vocal campus activists. The research inquired whether the students felt safe on campus and whether they agreed or disagreed with depictions of campus as “hotbeds of anti-Semitism and anti-Israel activity,” to which the study participants disagreed.

An SF State student interviewed on the condition of anonymity said that after learning about the tensions on campus, they first became more involved in SF Hillel and aligned organizations such as the David Project. They wished to show that not all Jewish students on campus are pro-Israel, but they cut ties once they realized that SF Hillel was at its core a pro-Israel organization. This led them to ultimately disconnect from Jewish student life and hide their Jewish identity at SF State.

“I definitely never felt comfortable wearing anything openly that was Jewish,” the student said. “I never wanted to have my Jewish star open when I wore one. I never felt like it was something that I would openly want to be expressing for some reason. If the topic came up, ‘Oh you’re Jewish,’ Israel would follow, and I didn’t — I don’t — have a firm stance on it ’cause it’s a complicated issue, and so I didn’t like being constantly put on the defensive for that.”

“Generally with Jewish pride comes the assumption of Israeli pride. It’s like, ‘No, actually.’ So that I remember is the main thing, always needing to have an opinion on Israel, and it always being the wrong one depending on who you were talking to.”

Summary of “Safe and on the Sidelines,” a Stanford study conducted by the research group concentrating in Education and Jewish Studies. (Dyanna Calvario / Golden Gate Xpress)

The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict on Campus: Palestinian Student Experiences

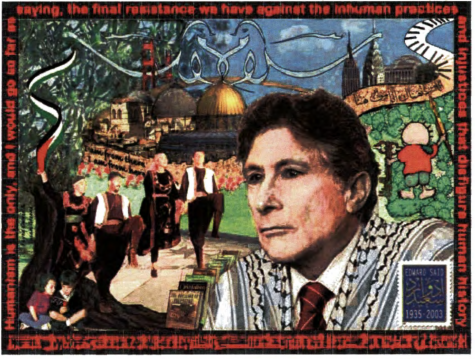

Hundreds of people walked past or under the mural portraying Edward Said while heading to class or entering the bookstore.

A second-year Palestinian student recalled looking at the Edward Said Mural almost everyday while walking around the SF State campus. They remembered the contemplative gaze of the Palestinian academic portrayed in front of a background weaving a depiction of SF State’s Malcolm X plaza with iconic landmarks from New York City, Jerusalem and San Francisco. Two cloud-like doves stand out in the bright blue sky, their intertwined figures spelling the word for “peace” in Arabic.

“Something that brings me a lot of joy as a Palestinian on campus is the mural,” the student said, speaking on the condition of anonymity. “Every time I see it, it just makes me happy that there’s something that’s a part of us that is visible on campus.”

The mural, which celebrates Palestinian heritage and commemorates the late writer, academic and human rights activist Said, was completed in 2007 — after almost three years of objections, leading to an eventual redesign. It joined multiple murals on campus that display students’ backgrounds and leaders such as Malcolm X and Cesar Chavez, illustrating the history and efforts of various social justice movements.

“The reason I chose SF State was more about, ‘I like it here’ and ‘I like that there’s like the one and only [General Union of Palestine Students] that’s left here,’” said another Palestinian student who spoke on the condition on anonymity. “I like that there’s a Palestinian mural. It kind of just makes it feel like I’m meant to be here.”

For other Palestinian students, SF State’s history of student activism and social justice was a reason to attend the university.

Although these students value aspects of the university that celebrate their identity, such as the mural of Said, this feeling of acceptance often fades when students hear about and experience attacks from pro-Israel organizations. Students have said that this sense of vulnerability has been exacerbated by a lack of support — and at times, vilification — from administrators.

For many students, the potential consequences of expressing weigh heavily against their freedom to express their identity and advocate for justice in and for Palestine.

When presented the initial draft of the mural by students, administration representative Richard Giardina suggested creating a policy to equally allot space to all student groups, saying that “problems could occur on campus” if other student groups opposed this mural. A subcommittee for the mural was approved in a 6-2 vote, with Giardina voting against it.

A week before the subcommittee planned to present its design to the main board, then-President Robert Corrigan wrote to the board, “The proposed mural is conflict-centered … Its spirit is less of a celebration than of challenge. In short, it is at odds with the most fundamental values to which San Francisco State University is committed.”

He asked the student board to send the design back to the arts committee rather than let it move forward. The board approved the design despite these concerns, and Corrigan placed a moratorium on all murals until the board created a new mural allocation process that the president’s cabinet approved of.

READ MORE about the different images and meanings of the Palestinian Cultural Mural featuring Edward Said on either Art Forces or Fayeq Oweis websites.

The initial design included Handala, a cartoon refugee child created by Palestinian artist Naji al-Ali, holding a pen in one hand and an old-fashioned key in the other. Corrigan wrote that these images were “explicitly offensive and identified with an international conflict, rather than celebratory of the Palestinian-American experience and culture.”

The key symbolizes the right of return for Palestinian refugees. Many Palestinian students in GUPS have been the grandchildren of those made refugees in the 1948 Nakba — the mass expulsion of Palestinians from their homes.

“I know plenty of Palestinians who keep their deeds to their homes and their keys, and that’s what that is also about — going back home,” said Noel Madbak, a 2019 SF State graduate. “But supposedly it was never our home, so I think it’s telling how threatening the key is. Because some people interpret the idea of us going home to mean we would kill them or go to war, but it shouldn’t have to be like that.”

However, some Jewish students and community members saw the symbols as representing hostility and political resistance to Israel, saying the symbols would send a chilling message to Jewish students and any supporters of Israel on campus. The right of return is seen as a threat to them because if all Palestinian refugees were to return to their old homes, it would change the demographics of Israel as a Jewish-majority state.

“In short, the Palestinian key is more than just a key, just as a conical hat on the top of a man dressed in white robes is more than just a hat,” wrote both the president and the executive director of the Jewish Community Relations Council in an op-ed for The Jewish Weekly News of Northern California.

In a dissertation on Israel’s Significance to American Jews, focusing on Bay Area experiences, Sarah Anne Minkin wrote how this view from the JCRC “collapses the expression of Palestinian identity with violence and race-hatred, closes off the possibility of viewing Palestinian self-expression as anything other than threatening to Jews.”

Because Corrigan didn’t approve the Palestinian mural until the images were removed, Palestinian students and allies felt the university blatantly sided with the JCRC, which praised Corrigan for his response. Palestinian students today remember him as someone who institutionalized the view that symbols representing Palestinian culture and political expression are threatening to Jewish students.

Upon hearing about this history of censorship from other students, Palestinian students who saw the mural as a reason they belonged at SF State said they felt at odds with the campus and the role of the administration in supporting social justice.

“It’s mixed emotions for me,” Madbak said. “I’m happy that we have a Palestinian mural. I’m proud of all the people that came before me that were able to make that happen. But it also makes me very sad that we couldn’t have things like the key on our mural that symbolizes our right to return to our homeland because that was too controversial.”

Madbak first joined GUPS in 2016, after SF State student organizations protested SF Hillel’s invitation of then-Jerusalem Mayor Nir Barkat to speak on campus. She felt the administration’s allowance of someone Palestinian students and others saw as threatening contradicted the university’s mission statement of social justice. GUPS student leaders found out about Barkat’s scheduled appearance at the last minute and came together with other student organizations to protest.

The university received criticism from Jewish faculty, students and community members and organizations over how it handled the protest and how members of the university police and administration failed to stop Jewish students and Barkat from being yelled over by protesting students. Dozens of emails, obtained through a public record request by the Lawfare Project, asked then-President Leslie Wong to investigate and punish the two Palestinian students who led the chants. Administrators threatened the students with expulsion and disciplinary procedures; however, a third-party investigation paid for by the university found administrators at fault rather than the students.

The two female Palestinian students involved in leading the chants were followed on campus and received rape and death threats, along with calls for their employment termination. An online blacklist compiled their photos, workplaces and social media, while others publicly shared their personal information.

Though Palestinian students have described experiencing a continual lack of support by the university administration in the midst of harassment from groups outside SF State, they have found continuous support from student groups on campus. In particular, they attributed members of historical campus organizations, such as the Student Kouncil of Intertribal Nations, whose members suggested and encouraged GUPS to propose a mural in 2005.

At an April 9, 2019 rally, the League of Filipino Students led a call and response. “I said ‘Rise up, rise up, rise up.’ Rise up, rise up, rise up. I said, ‘Rise up, my people rise up.’” Later, students led chants of, “From Palestine to the Philippines, stop the U.S. war machine.”

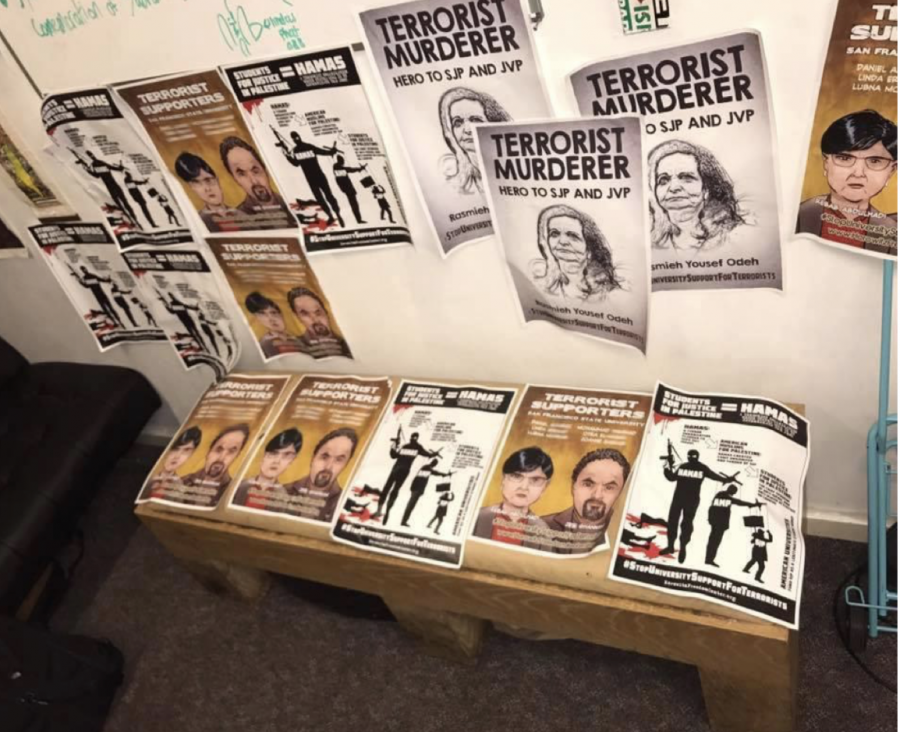

Many students emphasized that GUPS has given them a sense of community and joy, but their involvement with the organization is still riddled with double standards, accusations of antisemitism and concerns about potential retaliation for their beliefs and actions. These concerns have been persistent and haunting, especially considering the methods used by organizations such as the David Horowitz Freedom Center — known to plaster college campuses with posters listing the names of professors and students they claim have ties to terrorist organizations.

Palestinian students and a Palestinian professor at SF State have received Islamophobic death threats and hate mail.

Islamophobia often targets Palestinian students and supporters; however, Palestinian, Arab and Muslim identities are not synonymous. Not all Palestinians, Arabs or Muslims have the same viewpoint, politics or understanding of Palestinian identity or the issues around the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Nationally, students involved in Palestinian activism say they fear creating a social media presence, being quoted in newspapers or showing up at protests that could have them end up on a website that catalogs people as antisemitic.

Canary Mission is one website well-known by students involved in Palestinian-related activism. Its mission statement claims it focuses on documenting antisemitic individuals and organizations on North American college campuses that promote hatred of Israel, Jews and the U.S. This may include anyone who supports the Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions Movement or disrupts Jewish or pro-Israel speakers.

Canary Mission’s database consists primarily of Arab and Muslim students and professors, though there are also Jewish students, non-Arab or non-Muslim academics and activists, as well as white supremacists. The profiles are also updated — some created in 2016 were updated in March and include a full range of social media information.

“I’ve always been hesitant to participate in anything public with GUPS that’s open to the rest of campus,” said a student in GUPS who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “I’m worried that I might end up on Canary Mission … I was always nervous about being singled out or recorded or someone using my speech or something I do against me. Especially on campus.”

Students say the blacklist villainies those advocating for justice in and for Palestine. It has instilled fear in students for their safety. Students are aware it could also affect their future employment or educational pursuits. Still, some refuse to suppress their beliefs.

“It just makes me want to work harder,” said Sabreen, the current president of GUPS. “What I’m standing up for is right and just, and [Canary Mission is] not going to stop me from continuing my work for the liberation of Palestine … If somebody doesn’t want to hire me because of my beliefs, then like, fuck it.”

According to tax documents obtained by The Forward, the San Francisco Jewish Community Federation donated $100,000 to Canary Mission through a supporting foundation in 2016. The JCF and its Endowment Fund manages $1.6 billion in total assets and donates to many progressive institutions around the world.

The JCF responded that it has reviewed its policies and guidelines and that it will not support Canary Mission in the future. However, in the past, the JCF and a supporting foundation also gave to the David Horowitz Freedom Center and other right-wing and anti-Palestinian organizations, and the JCF has continued to donate to anti-Muslim hate groups and media sites such as the Clarion Project and Middle East Forum.

The impact of Canary Mission goes beyond concerns for job and graduate school prospects. The Israeli Defense Forces use Canary Mission when questioning and screening people coming into Israel or the West Bank. For Palestinian students with family there, the potential to be denied entry when visiting family has additional consequences.

“It’s also scary, because even me doing this [interview] and me being involved, it could potentially impact me ever going back to Palestine,” said a student with family in Palestine who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “Like, this really affects our lives in ways it doesn’t affect people from Hillel’s lives. For them, it doesn’t affect them if they want to go back to the Middle East.”

In March 2017, Israel began denying entry visas to foreign nationals who advocate for any form of a boycott against Israel or the West Bank settlements. The country has barred Palestinian and Jewish activists and students from entering as a result. This law was used to initially ban entry for Congresswomen Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib in 2019.

That same year, a contentious definition of antisemitism was enshrined in an executive order by President Donald Trump, causing concern among Palestinian students and public university administrators about potential legal action against them or loss of funding.

Citing antisemitic harassment on college campuses, the executive order stated that departments and agencies enforcing Title VI — which prohibits discrimination based on race, national origin or color in programs receiving federal funds — must consider this working definition of antisemitism. In particular, this includes contemporary examples of antisemitism such as denying the Jewish people their right to self-determination by claiming Israel is a racist endeavor.

Jared Kushner wrote in a New York Times op-ed, “[This definition] makes clear what our administration has stated publicly and on the record: Anti-Zionism is anti-Semitism.”

“This executive order is not about protecting Jewish students or to actually address anti-Semitism like the growing amount of white supremacist groups on university who continue to organize with no repercussions,” wrote GUPS in a Dec. 11 statement. “This is about silencing Palestinian student organizers, faculty, and any ally that speaks up for the rights of Palestinians and to all who push for BDS on their campuses. It is clear what this executive order is, to silence any criticism of Israel and to silence the growing powerful voice Palestinian student organizers.”

The lead drafter of the definition of antisemitism used in the order, Kenneth Stern, has spoken out against Trump’s executive order. He expressed concern that it will have a “chilling effect” on campus free speech, as administrators worry about being sued, and the government gets to define how Zionism fits into Jewish identity — something he acknowledged is debated within the Jewish community.

Earlier this month, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo made an unprecedented visit to an Israeli settlement in the West Bank. Pompeo said the Trump administration plans to label all products from the settlements — illegal under international law — as products of Israel. He also announced the usage of the working definition of antisemitism in labeling the BDS movement as antisemitic and “a cancer,” promising to cut government funding to organizations that support it.

Amid the threats of blacklists and surveillance, these government actions have only heightened concerns by groups of students that their freedom of speech is restricted at SF State — fears that students said the college administration has left unaddressed.

“I think most students don’t realize how serious it actually is … like, ‘We live in San Francisco, this is America, you have freedom of speech,’ but actually no it’s not like that,” said Palestinian student, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “Coming here, I realized it’s not that simple.”

Excerpts from “Palestinians say their free speech is endangered,” written by Norma Shiheiber Sayage in the Golden Gater, published on March 10, 1987.

The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict on Campus: The AMED Studies Program

“Life-changing” is how SF State alum Noel Madbak described the classes she took that delved into her identity and her family experiences — something she said she never encountered in an academic space before the Arab and Muslim Ethnicities and Diasporas Studies program.

“I never had Arab teachers,” Madbak said, reflecting on her primary and secondary school years. “I never had teachers who ate the same food as me, who spoke the same language as me … who understood the struggles my family went through as refugees.”

Madbak, who graduated in Fall 2019, said she signed up for the minor after taking the Palestine Ethnic Studies Perspective course. She said that class and other AMED courses excited her as they validated the experiences of her Palestinian parents and grandparents.

Though Madbak describes a sense of fulfillment from AMED coursework, she and other students are simultaneously disappointed with what they say are a lack of university support for the program and frequent attacks against Palestinian students and professors — both of which, Madbak said, attempt to stifle meaningful discourse around Palestine, Palestinians and their history.

Creating the AMED program was an intentional step toward reducing friction on campus around the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; however, the past 18 years have seen more conflict as a program meant to increase education has drawn ire and pushback at times from school administrators and attacks from outside organizations.

Rabab Abdulhadi is the senior scholar who has built and directed the AMED program since its inception in 2006. A Palestinian born in Nablus, Abdulhadi holds two master’s degrees and a doctorate from Yale University. The program curriculum, inspired by the spirit of the ’68 student strike, focuses on the lived experiences of Arab, Muslim and Palestinian communities through a framework emphasizing shared liberation — what Abdulhadi calls the indivisibility of justice.

“AMED’s curriculum is designed to provide students with a core base of knowledge around the history, issues and challenges relating to Arab, Muslim and Palestinian diasporic communities while developing their critical thinking, pedagogical reasoning, and analytical processing abilities,” Abdulhadi wrote in a 2009 draft for the proposal of the AMED minor.

Abdulhadi began developing the AMED program before she was hired. She left her position as the first director of Arab American Studies at the University of Michigan to head SF State’s new program in January 2007, with the understanding that two additional full-time faculty members would be hired.

Thirteen years later as the senior scholar and sole full-time faculty for the program, Abdulhadi said she feels alienated by the administration and unsupported when facing attacks from outside groups.

THE START OF ARAB AND MUSLIM STUDIES AT SF STATE

Campus protests concerning the Israeli-Palestinian conflict increased in the early 2000s — a period marked by events such as the second Intifada and increasing violence in Israel and Palestine, Sept. 11 and the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq.

“We couldn’t generate enough interest amongst the students in that field [Middle Eastern, Islamic and Arab studies] as much as we tried,” said Emeritus Jerald Combs, a former History Department professor from 1964 to 2006. “But 9/11 changed things drastically in generating student interest. Our Middle Eastern courses were filled, and we were hiring people across the campus and in other disciplines with Islamic or Arab emphasis. Students were very interested because it seemed very relevant.”

In 2003, the university hired four faculty members in the fields of comparative politics, anthropology and philosophy. They and existing faculty formed the Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies program, which became a minor in 2007. It currently has 17 contributing faculty from various disciplines.

Tensions on campus came to a head during a rally on May 7, 2002, “We Stand with Israel: Now and Forever.” Organized by SF Hillel students, the rally brought approximately 350 campus and community members to the Malcolm X plaza for the rally — along with 75 protesters.

The university’s president at the time, Robert Corrigan, responded with a message that condemned antisemitic speech.

“A small but terribly destructive number of pro-Palestinian demonstrators, many of whom were not SFSU students, abandoned themselves to intimidating behavior and statements too hate-filled to repeat,” Corrigan stated.

Students in the General Union of Palestine Students published their own summary of the event at the end of May, expressing their frustration with what they said was one-sided and biased media portrayals. They noted the absence of coverage or acknowledgement of anti-Arab and Islamophobic phrases shouted at the event. “Go fuck a camel” was one expletive said by a Jewish student who was afterward assigned community service by the university.

The summary also included list of demands such as the creation of an Arab and Muslim studies program to “ensure Academic freedom and a fair and balanced course offering.”

A month later, Corrigan created what became a 42-person task force of university and community representatives to address recent issues and concerns of Jewish and Palestinian communities. He also issued a letter of warning to SF Hillel, sanctioned GUPS for a year because of the May 7 rally and announced a “Year of Constructive Civil Discourse” at SF State focusing on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict through film screenings and panel discussions.

The task force concluded in its preliminary and final reports that the university should create curriculum focused on Arab and Muslim communities globally. They envisioned an interdisciplinary program or minor that could develop into a Bachelor of Arts anchored by core faculty in the College of Ethnic Studies. It recommended a model paralleling the Jewish Studies Department, which at the time had two full-time faculty.

“The College of Ethnic Studies’ entire existence and presence is really important within campus life,” said Ariana Khateeb, a current Palestinian student who has taken an AMED course. “Adding those classes are beneficial to students who aren’t Arab or Muslim, who could really learn from those courses. It is important to have that option open for students regardless [of enrollment numbers].”

DEVELOPMENT OF THE AMED PROGRAM

The Race and Resistance Studies Department and COES emphasize collaboration between communities and academics and prioritizing justice-centered learning. The AMED program aims to embody these themes by hosting classes and events open to the greater community and posted online. Its addition to the COES marked the college’s first expansion upon traditional ethnic studies areas.

Kenneth Monteiro, former dean of the COES for from 2004-17, described the intentional inclusion of AMED into Ethnic Studies as a major feat pushed forward by extensive peer review and community scrutiny.

“This addition enriched the lives of students and faculty who are parts of the communities represented in AMED, and also expanded the educational opportunities for those of us who are not,” Monteiro wrote in an email.

Click HERE to read more about the fight for Ethnic Studies in the CSU system as a requirement.

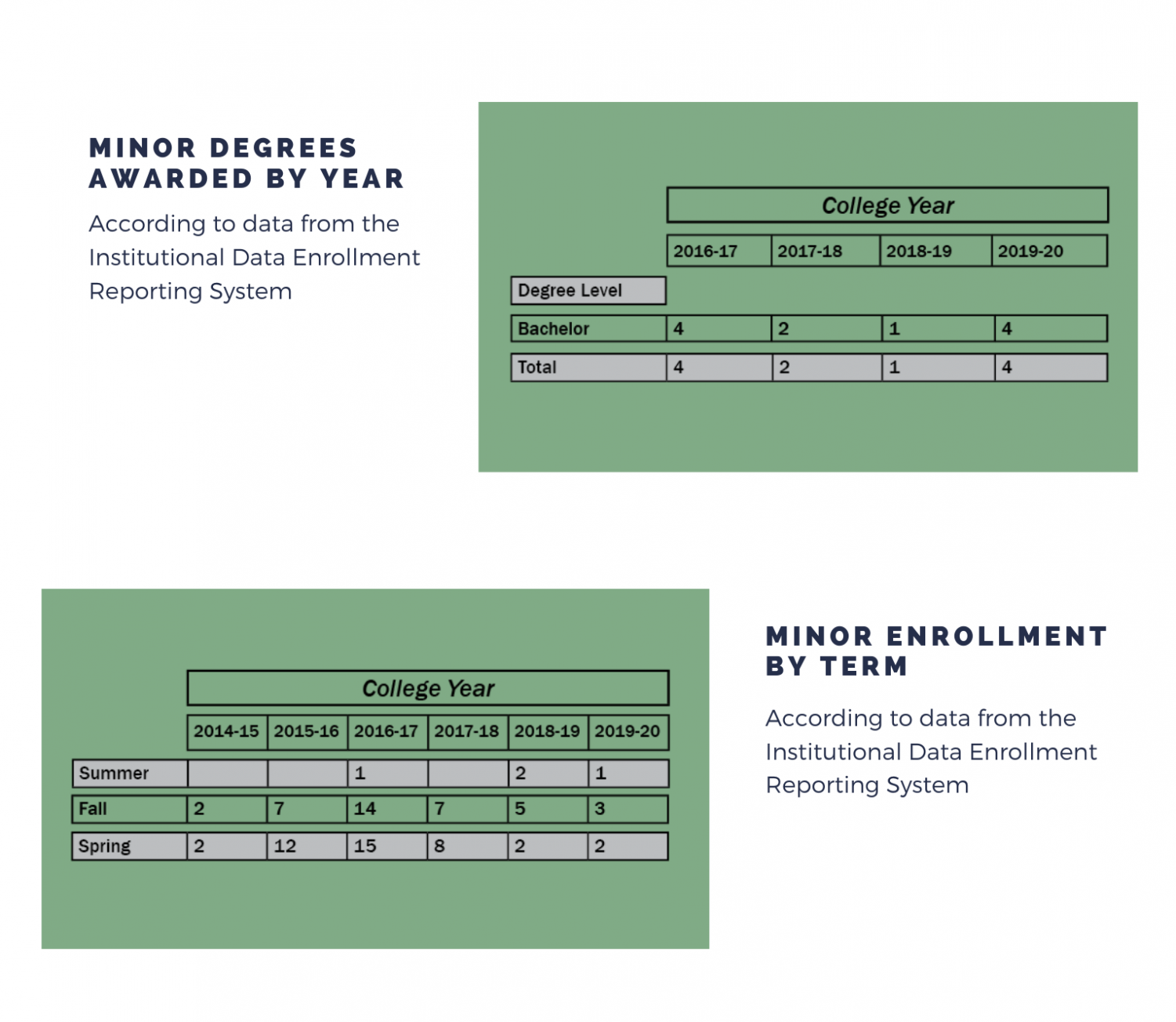

In March 2015, the AMED program created a minor with 22 approved courses meeting multiple SF State Studies and general education requirements. The Edward Said scholarship was first awarded in the 2015-16 school year to help financially support undergraduate and graduate students involved with AMED. Abdulhadi also established a memorandum of understanding with the An-Najah National University in Palestine.

Abdulhadi and James Martel, president of the SF State chapter of the California Faculty Association, maintain that despite its successes, AMED has taken a back seat to Race and Resistance Studies — which became a department in 2017 — and AMED has not been able to develop into its own department as intended.

“AMED at its core is really so much about this indivisibility of justice and looking at interconnected struggles. It makes me very sad to know that all of this exists, because if the resources promised were there, then I think students would be walking away honestly transformed,” said Heather Abu Deiab, a student who self-designed her undergraduate major to center on AMED courses. She went on to become a research assistant to Abdulhadi and AMED as she obtained her M.A. in Ethnic Studies at SF State. “Because I know it’s really a transformative academic experience taking these courses.”

ISLAMOPHOBIC ATTACKS

Abdulhadi was subject to harassment and aware of the targeting of Palestinian academics before coming to SF State.

Since coming to the university, she said these attacks have only intensified. She has faced numerous attempts to defame her and discredit her work by pro-Israel groups such as the David Horowitz Freedom Center, AMCHA Initiative, Campus Watch and the Lawfare Project.

Degrading caricatures featured on posters have been plastered regularly throughout campus, alleging ties between Abdulhadi and terrorist organizations and accusing her of being antisemitic. Threatening voicemails and physical hate mail have made Abdulhadi fearful to walk alone on campus.

An Islamophobic hate letter for Abdulhadi was sent to the administration on May 25, but the university did not inform her until June 22 — a decision made by the administration, saying that “no one needs this kind of negative input.” The associate vice president of Student Affairs wrote that they submitted the letter to the University Police Department for their records.

“The University takes the safety of its faculty very seriously,” SF State President Lynn Mahoney wrote in an August email regarding hate mail sent to Abdulhadi. “We have worked and will continue to work with Professor Abdulhadi if she should receive threatening messages or believes that her safety is at risk, as we do for all faculty.”

Various pro-Israel Jewish organizations have petitioned the university and California State Controller to audit Abdulhadi’s academic travel, leading to multiple university audits.

In one instance, the AMCHA Initiative called upon the university to audit a delegation trip where Abdulhadi met with Leila Khaled and Sheikh Raed Salah in Palestine. Receiving backlash for meeting with Khaled and Saleh, Abdulhadi and those in the delegation noted that they arranged to meet with almost 200 individuals to gather a range of perspectives.

Abdulhadi was ultimately exonerated of all these accusations.

“Professor Abdulhadi, primarily, with the assistance of various colleagues and students, wrote and ushered through the approval process for the new classes and the minor degree program that you can find online,” Monteiro wrote in an email. “She did this despite fending off one of the most active hate campaigns against any individual that I’ve seen across more than three decades at SF State.”

Throughout the years, multiple strikers from the 1968 strike, which led to the founding of the COES, have expressed support for Abdulhadi and the AMED program, writing that the campaigns against Abdulhadi and her students for being outspoken advocates for justice also attack the COES and spirit of their strike.

ADDITIONAL HIRES — AN UNFULFILLED PROMISE

Since her arrival at SF State in 2007, Abdulhadi has been the only professor hired specifically for the AMED program, though the program has received supplemental support in the form of student research assistants, visiting scholars and lecturers over the years.

She is currently involved in state and federal lawsuits suing the California State University system and SF State for alleged discrimination as a Palestinian and Muslim woman with disabilities. At a Nov. 13 hearing for the state lawsuit, a California Supreme Court judge overturned a request by the university to dismiss the case and ruled to proceed with the lawsuit.

The lawsuit alleges that the university has failed to provide protection or support from Islamophobic attacks by outside parties and that top administrators have referred to her in derogatory ways because of her nationality, gender and religion. The lawsuit also alleges that the university has not fulfilled Abdulhadi’s hiring agreement — primarily, a promise to hire two additional faculty for the program she was hired to develop and direct.

The Memorandum of Understanding when hiring her states, “The university will support two additional lines in the areas of Arab/Islamic studies.” These were to first be opened as research assistant jobs and converted into tenure-track positions after Abdulhadi submitted necessary documents for the approval of the university provost.

Abdulhadi said this commitment strongly influenced her to come to SF State, but the university has continually dismissed it for the past 14 years.

Mahoney wrote in an email that the promise of two faculty hires predates her arrival in July 2019 by several years and is part of ongoing litigation. She wrote that new faculty appointments are currently awarded based on student demand and enrollment.

“I don’t feel like I have the luxury to walk away, because I’m the only professor at AMED,” Abdulhadi said in an April 23 Zoom conference with Students for Justice in Palestine, discussing campus repression of Palestinian scholarship and activism.

Abdulhadi said then-president Robert Corrigan cancelled searches for the two tenure-track faculty positions when they were near completion in late 2009.

Corrigan and then-Provost Sue Rosser cited the 2008 financial crisis and a lack of outside fundraising as the reason the faculty positions could not be funded. Abdulhadi, however, said the positions had already been in the approved budget since she was hired in 2006. She, alumni and community members added that the cancellation coincided with the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement co-founder Omar Barghouti’s invitation to speak at SF State, as Corrigan wrote that academic boycotts are dangerous.

Abdulhadi, along with Arab, Muslim and Palestinian community members supportive of AMED, were hopeful that Leslie Wong would provide administrative and financial support to the program when he took the helm as university president in 2012.

Wong was initially supportive of the program and its students, Abdulhadi said. In March 2013, he met with the AMED community at the Arab Cultural and Community Center. He also spoke at the reception to celebrate the creation of the AMED minor in 2015.

The initial complaint filed for Abdulhadi’s lawsuit alleges that Wong’s support disappeared after he went on an all-expenses paid trip to Israel in March 2013 with the San Francisco Jewish Community Relations Council.

Monteiro said that in the years he was dean of COES, Wong and Rosser would not approve the two positions for hire. He wrote that current Provost Jennifer Summit also seemed disinclined to approve the positions and, at times, appeared to create the impression that the unfilled positions never existed.

However, Wong did renew the promise of two additional faculty for AMED when signing a negotiation with student hunger-strikers in 2016.

The students’ first demand included hiring two tenure-track faculty for the AMED program. While the original goals were not met, Wong agreed to regularly meet with interested students in AMED to develop a plan to reinstate the two tenure-track faculty lines within five years. In addition, he promised to provide operational support to the program.

Two students heavily involved in AMED at the time of the hunger strikes both said those regular meetings did not materialize, noting that they only met once with Wong on July 27, 2016, after repeated student requests. When directly asked about reinstating the two faculty lines, Wong said it was the role of the provost to approve them.

Students later reached out to Rosser. One of the two heavily involved students said that the provost claimed the positions were to be paid for by the existing COES budget, and that she refused multiple times to meet with students regarding the hires. Both students said they felt nothing significant came out of the meeting and that Wong dismissed their concerns.

Falu Bakrania, chair of the Race and Resistance Studies Department, said her department and the COES have requested the two hires for AMED nearly every year since the faculty searches were cancelled. Monteiro said that throughout his tenure as dean, the AMED program hires remained a standing request from the time the hiring searches were terminated by Corrigan.

“The program hasn’t been able to grow because it hasn’t gotten those hires,” Bakrania said. “We want the program to grow. It would be great if it could become a department.”

Abdulhadi said that the last time requests for the faculty lines were made was summer 2016, and that the actions of administrators — including those in RRS and the COES — have not demonstrated meaningful support to institutionalize the AMED program. She said her lawsuit against the university aims to hold administrators accountable.

THE START OF THE SEMESTER

Abdulhadi filed a grievance on Aug. 20 centered around the unfulfilled promise of additional faculty. Shortly before the Fall 2020 semester began, she was assigned to teach two Introduction to Ethnic Studies courses she had never taught before.

The grievance describes Abdulhadi’s assignment to teach Race and Resistance Studies courses as a breach of her hiring contract and violation of her original appointment as the AMED program’s director and senior scholar. It proposes hiring the two additional faculty to remedy the administration’s shortfall in fulfilling her memorandum of understanding.

Abdulhadi, along with alumni, community members and current students, met with Mahoney virtually on Aug. 21 to discuss what they described to be a lack of administrative support for the AMED program, along with the cancellation of two Palestine-specific AMED courses in April and Abdulhadi’s Arab and Arab Feminisms course. At the meeting, Mahoney said the cancellations were a budget decision out of her control and made no commitment to further develop the program.

The SF State chapter of the CFA passed a resolution in support of Abdulhadi and the AMED program the last week of August, and a recent Council on American-Islamic Relations report about Islamophobia on California college campuses mentioned the AMED program when referring to incidents of Islamophobia perpetuated by administrators or outside organizations.

“The cutting of AMED classes and inability to provide full time faculty remains troubling and has caused low student enrollment and an inability for the program to grow and thrive, as intended by Dr. Abdulhadi’s Pro-Israel Zionist detractors,” the Nov. 19 report stated. “CAIR-SFBA, as a member of the Friends of AMED Committee, advocated for a reversal of SFSU’s decision to delist AMED courses and force Dr. Abdulhadi to teach introductory courses outside her area of academic research.”

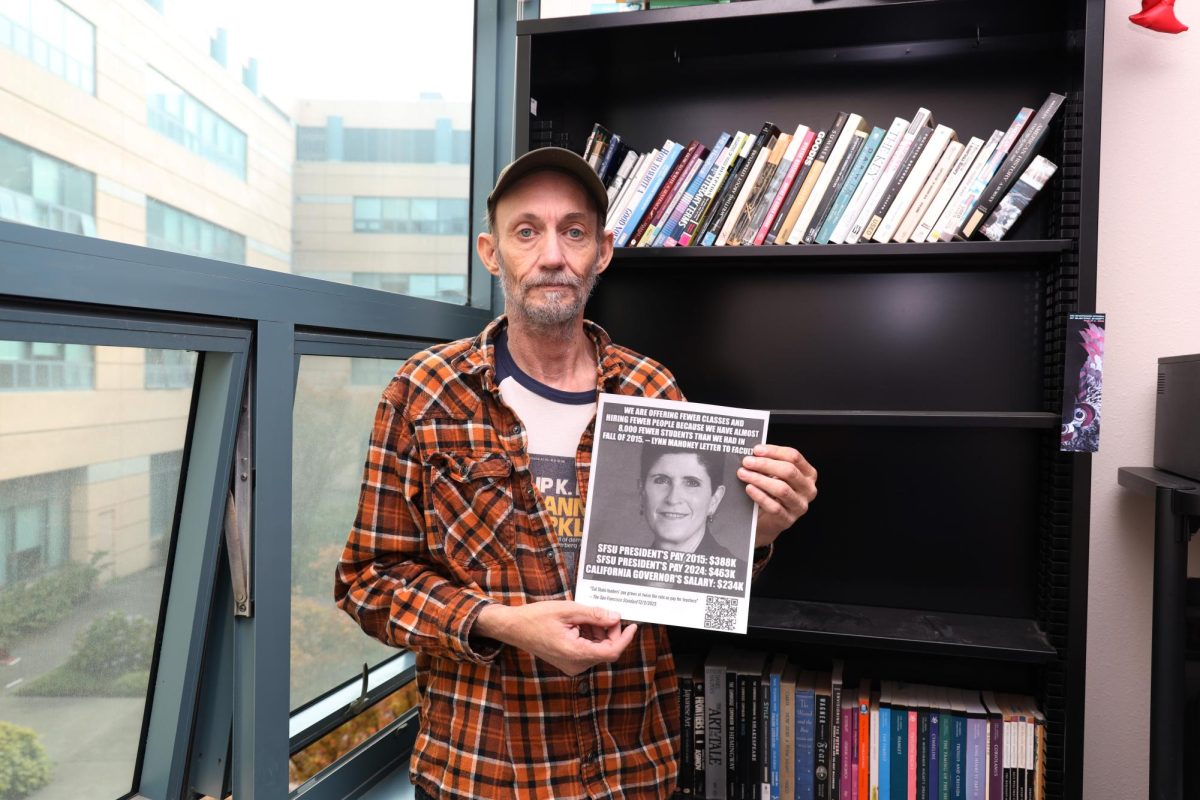

Mahoney cited the pandemic, loss of tuition funds and a $41 million budget gap for this academic year as reasons classes across the university were being cancelled. The university also laid off 131 staff members in September, which were finalized over the fall break. Staff and three SF Board of Supervisors have criticized the layoffs in light of the CSU’s $1.5 billion surplus discovered by the California State University audit released in 2019.

Martel said that despite the many programs, professors, staff and classes impacted by the current budget crisis, the situation with AMED is part of a longer history. He said that the lack of support is nothing new to AMED, adding that the administration is attempting to suppress the program out of fear of lawsuits and defamation.

“What they [the administration] won’t say is, ‘We’re afraid. We’re afraid of David Horowitz, we’re afraid of Canary Mission, we’re afraid of lawsuits, of the Lawfare Project that sued SF State successfully and the settlement,’” Martel said. “They can’t and they won’t say that, but that’s I think what’s going on.”

Students in the program see the administration’s actions as adding to the difficulties the program already faces.

“The administration is cutting all the classes,” said a Palestinian student planning to minor in AMED who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “If it’s only 15 units, it really should not be that difficult to get the minor. But at this point, I’m not even sure if I’ll be able to do it. Why would I take classes for a minor that I might not be able to finish? The entire COES is so necessary, and it opens students’ eyes a lot. My favorite classes so far have all been Ethnic Studies classes.”

The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict on Campus: Student Life Coordinators

When President Lynn Mahoney began her time at SF State in 2019, she had high hopes that the Jewish and Muslim student life coordinators within the Division of Equity & Community Inclusion in Student Affairs would ease tensions she knew existed between Jewish and Palestinian students and campus organizations.

The Division of Equity & Community Inclusion was created by the former university administration in 2017 and the coordinator positions were first posted online in December 2018.

“We have that diversity. The focus is going to be on bringing folks together,” said Mahoney in an interview with the Jewish Weekly News of Northern California last October. “I look forward to when the Muslim student coordinator and the Jewish student coordinator host an event together.”

Since the university began searching for two student life coordinators in December 2018, neither position has remained filled for much longer than a semester. The only time both positions were filled simultaneously was in November 2019, an overlap lasting about a month. Both positions are currently empty.

Students have questioned the effectiveness of Mahoney’s efforts to rectify decades of conflict but recognize that her administration has inherited a problem that stems from years of mismanagement by previous administrations. Mahoney’s introduction to the university follows the retirement of her predecessor, former President Leslie Wong. A large number of administrators in charge of overseeing and hiring the coordinators changed following his leave.

Mahoney said in August that she wants the campus to be a model for how universities can discuss difficult geopolitical issues, but stated in a September interview that she realizes there will be irreconcilable differences between Palestinian and Jewish students and organizations, and that she can’t speak for them being open to conversation.

Mahoney said in September that she hopes these positions will be filled by the end of the semester. In late November, Frederick Smith, director of the Division of Equity & Community Inclusion, wrote in an email that this timeline is accurate and likely. Smith said that the division is continuing to consult with HR for an internal candidate process. If an internal search and hire is unsuccessful, they will begin an external search for the positions.

After a state lawsuit was settled between Jewish students and the university, certain agreements made in the settlement involved the coordinator for Jewish student life. In the settlement, the university agreed to consult with the Jewish Studies Department when hiring the coordinator, to try filling the position within 90 days of the settlement agreement and to fill and fund the position for at least 48 months.

Smith said SF Hillel students and staff were highly involved in meeting candidates and the hiring process, as well as the overall creation of both positions. The Muslim and Jewish coordinator positions came to fruition after discussions between Luoluo Hong, former vice president of Student Affairs and Enrollment, and Sasha Presley, former student president of SF Hillel, and in consultation with the former executive director of SF Hillel.

Both Hong and Presley declined multiple requests for interviews about the creation of these positions.

“I think that [the Jewish student life coordinator] really is a chance to give Jewish students a voice on campus that isn’t restricted to Hillel or JAz or I-Team,” said Ben Lieberman, a current Jewish student. “It’s a way for us to be a part of this campus … having our voices heard as a group of Jews with varying identities and varying political ideologies and what that means to this campus and other students on this campus.”

Sasha Joseph, the Jewish student life coordinator during the Fall 2019 semester, said that at an open forum for the candidates she was able to answer questions from multiple students. Marc Dollinger, a professor in the Jewish Studies Department served on the hiring committee responsible for Joseph’s selection, as per the settlement agreement.

Joseph said that as coordinator, she focused on Jewish inclusivity on campus by tabling to provide information about Jewish holidays. She also coordinated multiple Shabbat dinners with SF Hillel and other student organizations, including the Indian Student Association, as part of her work in emphasizing partnership and collaboration.

“It’s important for the campus to acknowledge that there are other things going on for Jewish students that aren’t around Israel-Palestine,” said Joseph in an April interview. “And that isn’t all that Jewish students are thinking about.”

Joseph said she felt the administration was very receptive to students’ concerns and her ideas. Despite this, Jewish students interviewed said they felt not much changed in her short time at the university.

In an open letter to Mahoney from September, Jewish students in SF Hillel wrote that filling the position quickly and with a dedicated and qualified leader is important for fulfilling the university’s promise in aiding SF Hillel in its “ongoing dismantling of systemic antisemitism and anti-Zionism.”

Mahoney said in September that the search to fill these positions may take longer than the anticipated deadline as she seeks input from faculty and students. This is in part because Mahoney said, despite the search process being fair and inclusive, some felt there were not enough faculty nor student voices in the creation and hiring search of the previous Muslim student life coordinator.

Muslim students meant to benefit from the hiring of a Muslim student life coordinator said they were not given as much transparency, communication or involvement with the creation and hiring of the position. This included not being informed of the position’s purpose and how they could best utilize the position’s $8,000 budget.

Sarah Bouabibsa was elected president of the Muslim Student Association in Spring 2019 and officially started the role in Fall 2019 semester. Daniel Teraguchi, the interim director for diversity and student equity, first reached out to Bouabibsa on Sept. 4, introducing himself and asking students to provide input by creating an advisory board for the position. This message came almost a year after the job descriptions were first posted in Dec. 2018.

Bouabibsa, in addition to the former MSA president, was confused about the rationale for creating the position and said she was given no details about the purpose of the position. On Sept. 19, after Teraguchi met Bouabibsa at an MSA meeting, he emailed her dates for Sept. 23 and 24 campus forums, in which students could meet the position finalists. Smith said no students attended these forums.

Teraguchi and the students were unable to coordinate time to meet to discuss the position further or meet the position candidates. As a result, the search committee continued with their selection of Zarina Kiziloglu for the position without official student input.

In an email to Bouabibsa, Teraguchi repeatedly emphasized his want for input from “Muslim and the spectrum of Arab and Palestinian students.”

“This should have been a Palestinian student life coordinator if that’s what [the administration] wanted, because it affects Palestinians whether Muslim or Christian or whatever,” Bouabibsa said. “In their lack of nuanced understanding of religion and culture, they didn’t realize that Palestinian does not equal Muslim. And them choosing a Muslim student life coordinator is very telling of how they see the Israeli-Palestinian conflict — and they see it as a religious-based conflict. As opposed to this is about land, people being displaced from land.”

Administrators, including Mahoney and Smith, later met with MSA, MWSA, General Union of Palestine Students and the Afghan Student Association on Oct. 8, 2019. According to Noor Baig, current MSA president, after it was brought up in the meeting that the position was already close to being filled without student input, administrators said they wanted students to help shape the role.

After the meeting, Teraguchi wrote in an email to Baig that he would check with HR if students could participate at this stage of the hiring process, and that he could not promise any involvement until someone was hired. A week later, he wrote that the candidates could not be brought back to campus to meet with students. At the end of October, he emailed Baig and Bouabibsa introducing Kiziloglu.

A week before the Oct. 8 meeting, GUPS President Sabreen and leadership responded to the March settlement, calling on the administration to create coordinator positions for all marginalized religious communities.

“If the focus is not on Jewishness as religion, but as a cultural and ethnic group, we call for a coordinator of Arab and Palestinian life on campus,” read the statement, insisting on student input in the hiring process.

Sabreen, who was present at the meeting, said the administration discussed students both being part of the hiring process and shaping the position. She noted that she received no follow-up until a few weeks later, when Kiziloglu came to GUPS student office and introduced herself as the newly hired Muslim student life coordinator.

Professor Rabab Abdulhadi, current faculty advisor for MSA, the Muslim Women’s Student Association and GUPS, said as both the advisor for these student organizations and as the director and senior scholar for the Arab and Muslim Ethnicities and Diasporas program that she was not consulted by the administration or search committee.

She said that the university went beyond the terms of the settlement to include pro-Israel Jewish students, academics and community groups in the process of hiring the Jewish student life coordinator; she felt the exact opposite was true for the Muslim student life coordinator hired, and that to her knowledge, no student organizations nor outside community groups were able to give input on the position.

As the university continues with the hiring process for these two positions, administrators are focusing on making the positions part of a greater support network using input from faculty in the Jewish Studies Department, Museum Studies, and Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies programs.

Both Mahoney and Smith believe the positions will be filled by the end of the semester. At the time of publication, student leadership of SF Hillel, GUPS, MSA and MWSA have not been reached out to for further input on the positions.

The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict on Campus: Dialogue

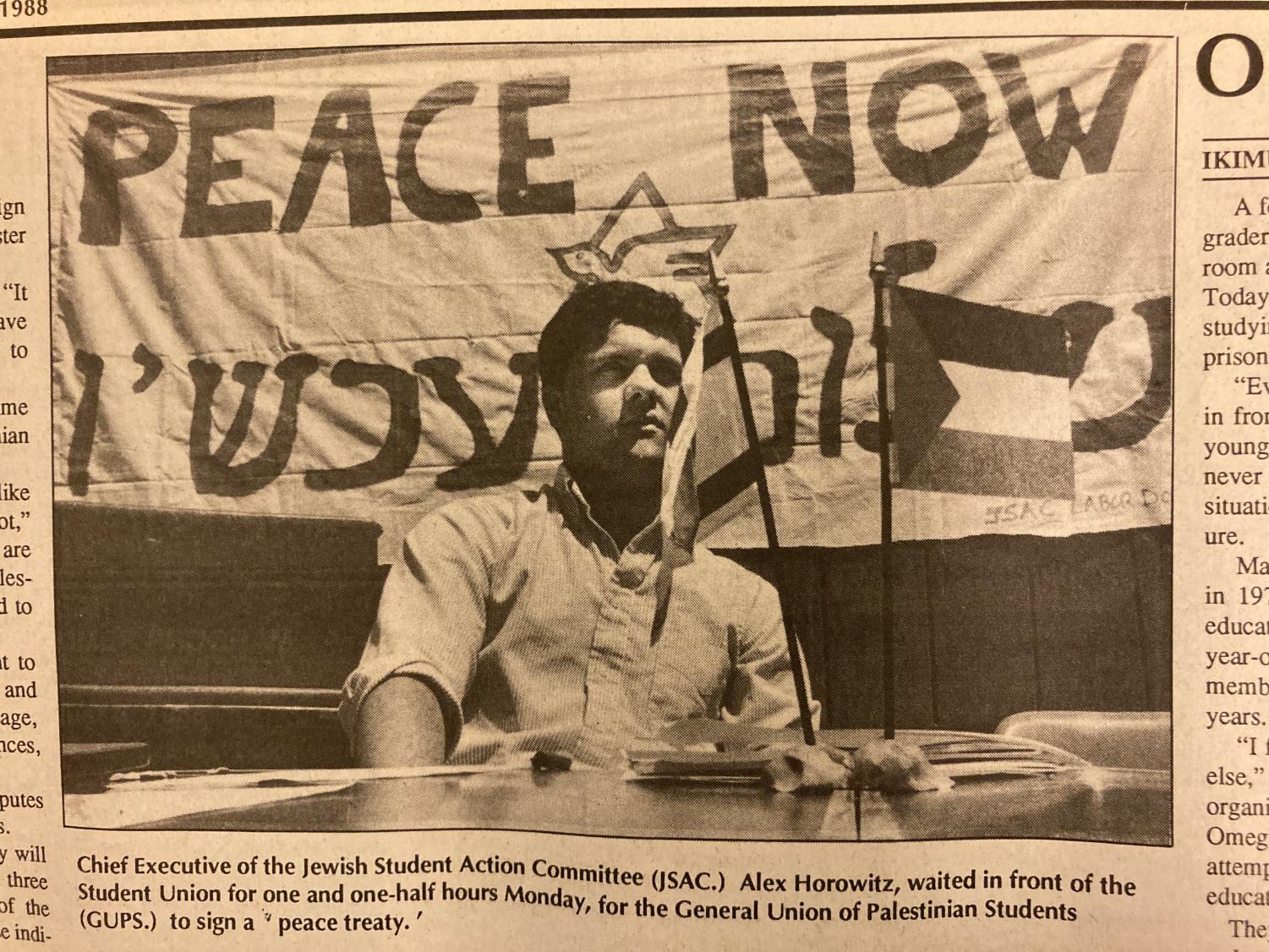

In May 1988, five years before the start of the Oslo Accords, Jewish students sat at a table underneath a banner with the phrase “Peace Now” in large fonts both in English and Hebrew. A dove was painted in the middle of the two slogans, and on the table were small Israeli and Palestinian flags.

Those in the now-disbanded Jewish Student Action Committee at SF State urged Palestinian students to sign their version of a peace treaty to send to Israeli and Palestinian leaders. The treaty was to act as a demonstration of peace on campus.

“We’ve worked out our differences, why can’t you?” JSAC Chief Executive Alex Horowitz said while tabling in 1988.

Palestinian students quoted said they were under no obligation to talk to other student groups, and that they viewed the symbolic peace treaty as a publicity stunt that detracted from the Palestinian students, whose family members were being killed by Israeli soldiers during the then-ongoing first Intifada.

“They (JSAC) want it to look like they are for peace and we are not,” Sami, a spokesperson for the General Union of Palestine Students, said in 1988. “The same time you are asking me these questions, the Palestinian people are being subjected to genocide.”

In some ways, this dynamic between some Jewish and Palestinian students remains unchanged. Students and alumni involved with SF Hillel say they want dialogue with Palestinian students on campus. These attempts usually come off as disingenuous to Palestinian students and allies, who say any such dialogue will fail to account for the power imbalance in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and gloss over the experiences of them and their families.

Shahni Ben-Haim, a former member of SF Hillel who graduated in 2018, said the climate and openness to dialogue in her current home in Tel Aviv, Israel, is much more receptive than what she experienced in her time on campus.

“With my background being Israeli American, those discussions weren’t welcomed, which is unfortunate as I feel if anything, I could have learned from my peers — even if it meant to agree to disagree,” Ben-Haim said.

Many blame anti-normalization, in which many Palestinians and other Arabs, Muslims or advocates of justice in and for Palestine refuse to normalize relationships with supporters of Israel and Zionism, due to the ongoing occupation impacting Palestinian students and their families.

“I believe people who say there needs to be dialogue don’t know the full history of the situation,” said Ariana Khateeb, a current Palestinian student. “So it’s very inappropriate to ask for dialogue because Palestinian students and Palestinians in general have been brutalized, killed, targeted and oppressed for the entire history between the two sides … It’s not a really productive dialogue when one side has to defend its right to exist.”

Anti-normalization has also been reaffirmed by anti-Zionist Jewish students and others who see attempts at dialogue by SF Hillel as hypocritical, because of Hillel International’s Israel guidelines. These guidelines also exclude anti-Zionist Jewish students, who often fear ostracization from their own community and families because of their solidarity with and support of Palestinian students.

Hillel International’s standards of partnership around Israel are clear. They state that Hillel chapters will not partner with, house or host organizations, groups or speakers that violate their Israel guidelines. These include those that “[deny] the right of Israel to exist as a Jewish and democratic state with secure and recognized borders,” support the [Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions] movement or “exhibit a pattern of disruptive behavior toward campus events or guest speakers.”

“I am unable to accept Hillel’s conditional support for its queer student group. I firmly believe that Hillel International’s Standards of Partnership present a litmus test for belonging in the Jewish community that is reductionist and exclusionary.” pic.twitter.com/mZZcAs8ezy

— Open Hillel / Judaism On Our Own Terms (@OpenHillelNow) April 22, 2019

According to SF Hillel Executive Director Rachel Nilson Ralston, SF Hillel brings a variety of speakers to express student views through different perspectives on topics such as Israel, Palestine, Zionism and the conflict overall. SF Hillel and Hillel International “reject the BDS movement because it squashes space for dialogue on campus and presumes a singular view about the resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict,” as she said SF Hillel opts for events that promote conversation.

Some looking to interact with others have called upon the administration to mediate dialogue.

Since starting at SF State in 2019, current university President Lynn Mahoney has met with students in GUPS and SF Hillel separately. Acknowledging that there will be strong disagreements, she said she wants the campus to be a place for courageous conversations between students.

On Nov. 18, the Associated Student governing board voted 17-2 to approve a resolution that calls on the administration to not invest in multinational and Israeli companies complicit in human rights violations, from a list compiled by the United Nations. The virtual meeting drew both passionate and bigoted comments from attendees, resulting in the board disabling the chat.

“San Francisco State University has had a decades-long challenge creating safe space for discussions about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict,” Mahoney wrote to Associated Students on why she cannot support the resolution. “We need courageous conversations, and we need to listen to one another without demonizing each other.”

Compilation of quotes regarding dialogue by current and graduated students (Jacquelyn Moreno / Golden Gate Xpress)

The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict on Campus: Timeline and Response to Lawsuits