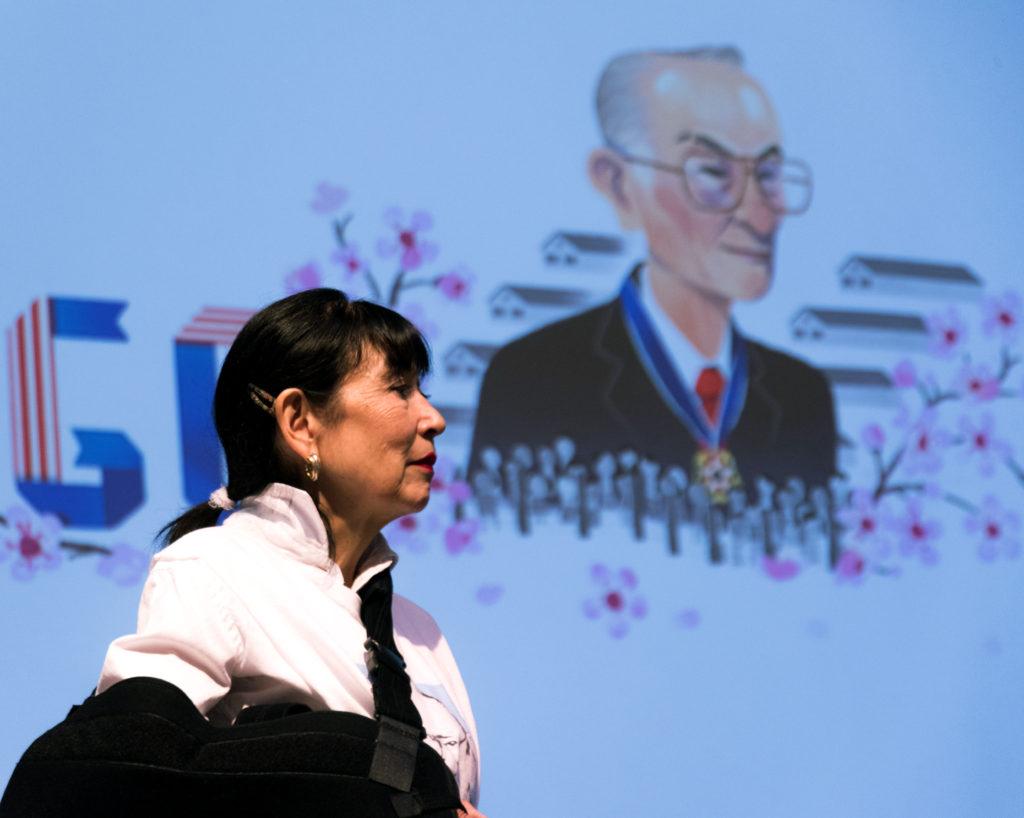

Fred Korematsu was an American hero who fought the government’s internment of Japanese citizens during WWII to the highest court in the country. Seventy-six years later, his daughter took the podium at Jack Adams Hall on Sept. 17 to talk about her father’s legacy.

Karen Korematsu began by making a point: How many in the audience came from families of immigrants? she asked. More than half in the crowd raised their hands.

“We are country of immigrants and it is not a dirty word,” she said. “It’s not something to be ashamed of. It is something to be proud of; that’s what built this country.”

Fred Korematsu, bravely opposed the forced internment of Japanese Americans during WWII in 1942, bringing his argument that the government’s actions were unconstitutional all the way to the Supreme Court.

His daughter pointed out how little has changed all these years later.

“Back then we called it ‘military necessity.’ Now we call it ‘national security,’” she said. “So, beware of all those euphemisms that we were using then and now.”

Karen Korematsu was at SF State after accepting history professor Marc Stein’s invitation to participate in the university’s annual Constitution and Citizenship Day Conference.

“There is timeliness aspect of the Korematsu case being in the conversation this year,” Stein said. “And … Japanese American internment is always of interest because for many of us, it just stands as a horrible example of injustice and racism and the use of national security to justify unequal treatment.”

Korematsu v. United States challenged Executive Order 9066 enacted in 1942 that ordered the forced removal of Japanese — regardless of their citizenship — from the West Coast of the United States.

The Supreme Court ruled against Korematsu, and on Dec. 18, 1944, the internment was ruled as constitutional. Last year was the 75th anniversary of the executive order.

The question at the time was, “now that we are at war, how do we treat people from those countries?” Korematsu said. “Could we ask that question now after 9/11? Interesting how these questions keep repeating themselves.

The same questions came up again during the Trump administration’s proposal to ban travel from countries of predominantly Muslim populations.

On June 26, 2017, in Trump v. Hawaii, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Muslim travel ban, Chief Justice Roberts gave the opinion of the court while referring to the Korematsu case.

“There was a very provocative exchange between two of the justices on the Supreme Court in the case concerning the Muslim ban,” Stein said. “Justice Sotomayor said that the Muslim ban is just like Japanese internment, and she noted that the Supreme Court had never overturned the decisions it made in the Korematsu case.”

Chief Justice John Roberts delivered the opinion of the court saying that he resents and objects to the comparison of the Muslim ban to the Korematsu case.

“Whatever rhetorical advantage the dissent may see in doing so, Korematsu has nothing to do with this case,” Roberts said. “Korematsu was gravely wrong the day it was decided, has been overruled in the court of history, and — to be clear — has no place in law under the Constitution.”

Roberts decision to uphold the Muslim travel ban while condemning the Korematsu decision was entirely incongruous, said Korematsu.

“In the same breath as upholding the discrimination and racial profiling of another group of people, he overrules my father’s case and marginalizes Muslims and all other minority groups,” she said.

SF State Asian American Studies professor Christen Sasaki, who introduced Korematsu, said Korematsu still gets emotional when she talks about her father’s case being overturned.

The Japanese felt shame after the forced internment was over. “You are accused of looking like the enemy, and it’s your fault,” she said. “If you are Muslim, or south Asian, or Middle Eastern in this country now, that the way a lot of these kids feel.”

Dr. Teresa Carrillo, Latina/Latino Studies professor at SF State, asked Korematsu what kind of connections she made between the legal challenges that her father’s case presented, and incarceration of families at the Mexican-American border.

Korematsu said that her father would have been disappointed in the detainment of families at the border and the separation of children.

“This is not something new, this is a parallel,” Korematsu said. “That’s why we need to stop repeating history, we need to learn from history to stop these injustices.”

Korematsu told students that if they are 18, they should register to vote. “Our constitution is nothing to be taken for granted,” said Korematsu. “We continually have to keep fighting for our constitutional rights.”