Editor’s note: This story will be updated as we continue to hear more from those close to and familiar with Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

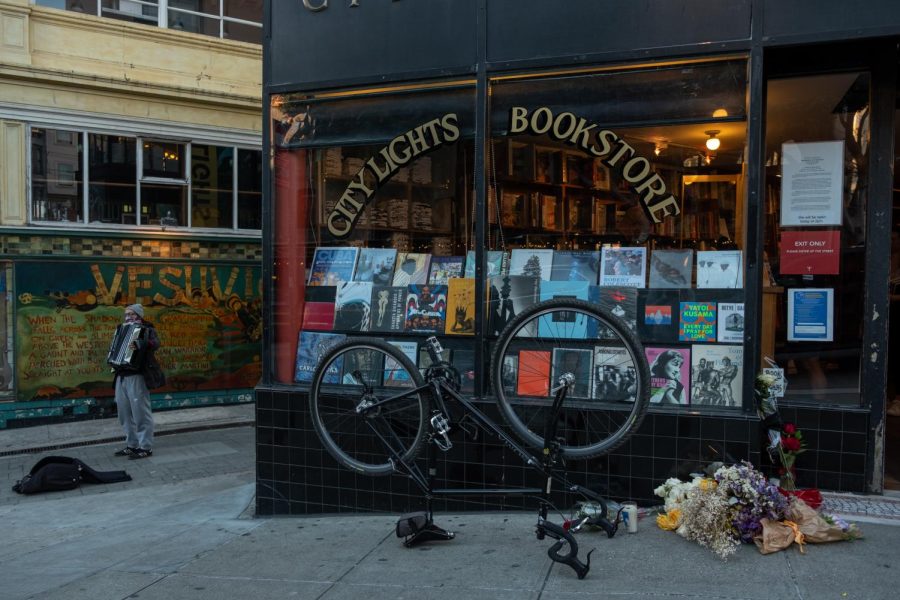

Lawrence Ferlinghetti, founder of the iconic City Lights Booksellers and Publishers and leader of the beat poetry movement, died Monday evening in San Francisco at the age of 101.

“Ferlinghetti was instrumental in democratizing American literature,” reads the statement from City Lights’ website. Ferlinghetti founded the iconic bookstore and publisher alongside SF State alum Peter D. Martin in 1953 and envisioned it as a “literary meeting place” for both writers and readers. Two years later, Ferlinghetti founded City Lights Publishers with the intent of promoting “wide-open poetry of engagement” and defending the right of freedom of expression.

Ferlinghetti would later be arrested by San Francisco Police Department for publishing “obscene work,” according to the City Lights website, when City Lights published Allen Ginsburg’s “Howl” in 1956. Following a lengthy trial that gained international attention and marked City Lights as pivotal to the beat poetry movement, the court ruled Howl as “not obscene”; City Lights was exonerated and paved the way for previously censored works, like Henry Miller’s “Tropic of Cancer” and D.H. Lawrence’s “Lady Chatterley’s Love,” to be published.

“By publishing Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” and defending it successfully in court against obscenity charges, he also made San Francisco a symbol of political, artistic, and sexual freedom,” said humanities professor Peter Richardson, who has taught the course on the biography of San Francisco previous semesters. “That’s only the beginning of what he accomplished as an artist, publisher, and bookseller. But that episode encapsulates his vision, courage, and independent spirit, which is still alive and well at City Lights.”

A 2017 article from the “European journal of American studies” by Dr. Gioia Woods, professor of humanities at Northern Arizona University, wrote, “Ferlinghetti … wished to capture the attention of the youth, the underclass, the disenfranchised,” and rejected the idea that only “highbrow” audiences understood poetry.

“Lawrence Ferlinghetti believed poetry should be taken out of the classroom and off the page and brought into the streets. It was the post-war populist poetry of Jacques Prevért that first shaped Ferlinghetti’s ethos as a public poet. From Prevért, Ferlinghetti understood that the poem was not an artifact, but a tool for urgent communication,” Woods said.

Ferlinghetti regularly visited the City Lights until the decline of his health, said City Lights staff member Stacey Lewis. Lewis said you would find him in the publishing offices of City Light’s top floor. Seated at his roll top desk, Ferlinghetti would be answering correspondences, responding to fan letters and looking over his current book projects.

According to Steve Dickison, director of the Poetry Center at SF State, Ferlinghetti’s first reading at the Poetry Center in 1956 has been the most popular recording for the Poetry Center Digital Archive website.

In the past two decades, Ferlinghetti hosted two benefit readings for the Poetry Center. The first reading took place in Club Fugazi in North Beach and was organized by Ferlinghetti and Dickison.

“Lawrence got in touch with the management, who were happy to waive any rental fee, and his solo reading drew a sold-out crowd to the benefit of The Poetry Center. It was a gracious and generous act,” said Dickison. “That went so well, a few years later we thought, ‘Let’s do that again.’”

Ferlinghetti returned to Club Fugazi in 2011, only this time he was accompanied by fellow beat poet Gary Snyder.

“Only this time we invited Gary Snyder to join Lawrence, with both of them reading their own work in shifts on stage. Both were excited to do this. Lawrence said he had never, in all these decades, read with Gary,” said Dickison.

In 1988, Ferlinghetti spoke to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors and proposed the idea to name several San Franciscan streets after literary figures. In addition to the renaming of Kerouac Alley behind the bookstore, other streets in San Francisco were named after literary figures, including Rexroth Place, located a block north of City Lights. Lewis mentioned that Kenneth Rexroth was a big influence on Ferlinghetti.

In 1998, former Mayor Willie Brown appointed Ferlinghetti as San Francisco’s first poet laureate. During his time as laureate, he wrote an ongoing poetry column, ‘Poetry as News,’ in the San Francisco Chronicle, and through the City Lights foundation, he initiated a series of commemorative books of poems by each successive poet laureate, according to the San Francisco Public Library,

Ferlinghetti had a plethora of titles in his resume. He was a WWII veteran, painter, writer, poet and activist, as well as business owner. City Lights carried early gay and lesbian publications. Two days after the assassination of George Moscone and Harvey Milk, Ferlinghetti penned a poem titled “An Elegy to Dispel Gloom” in the San Francisco Examiner.

“Lawrence Ferlinghetti held these noble roles: he was a publisher, a bookseller, and a popular poet, an almost impossible accomplishment,” said Dickison. “He and City Lights Books helped mark San Francisco forever as a city for poets and poetry. Where else can you go where anything like that is the case?”

Ferlinghetti continued writing and published his final book, “Little Boy,” at the age of 100.

“Ferlinghetti was more than a poet, or translator, or activist, or editor, or publisher, or painter, or business owner — he was a giant public intellectual of our time, showing us decade after decade that words matter. Words matter perhaps more than anything,” said Woods.

There is no current date for services, but Lewis encourages people to stay informed by subscribing to City Lights newsletter.