Asian Americans have a long and storied legacy in the United States. They’ve contributed to the American fields of law, medicine, film, art and more.

Out of the 48 countries in Asia, the Asian American community includes groups spanning the continent, many of whom have gone on to win some of this country’s highest honors and achievements.

Each community has a rich, distinct history of immigration to America that makes the lived experiences of different Asian American ethnic groups vastly different. The 2020 United States census numbered Asian Americans at around 19.9 million nationwide.

Medical research, public policy and healthcare, show that Asian Americans are continuously grouped into a singular category. In order to collect information from large sample pools researchers have traditionally used “aggregated data,” where data is combined from multiple individuals in a group. Reports made using that data make inferences about that population — in this case, Asian Americans.

In a 2020 study, researchers found that in every Asian American ethnic group that participated, at least one health disparity was hidden due to data disaggregation.

According to another study from the National Library of Medicine, diabetes is more prevalent in Asian American adults than white adults; among Asian American subgroups, diabetes rates were higher in Filipino Americans.

But why?

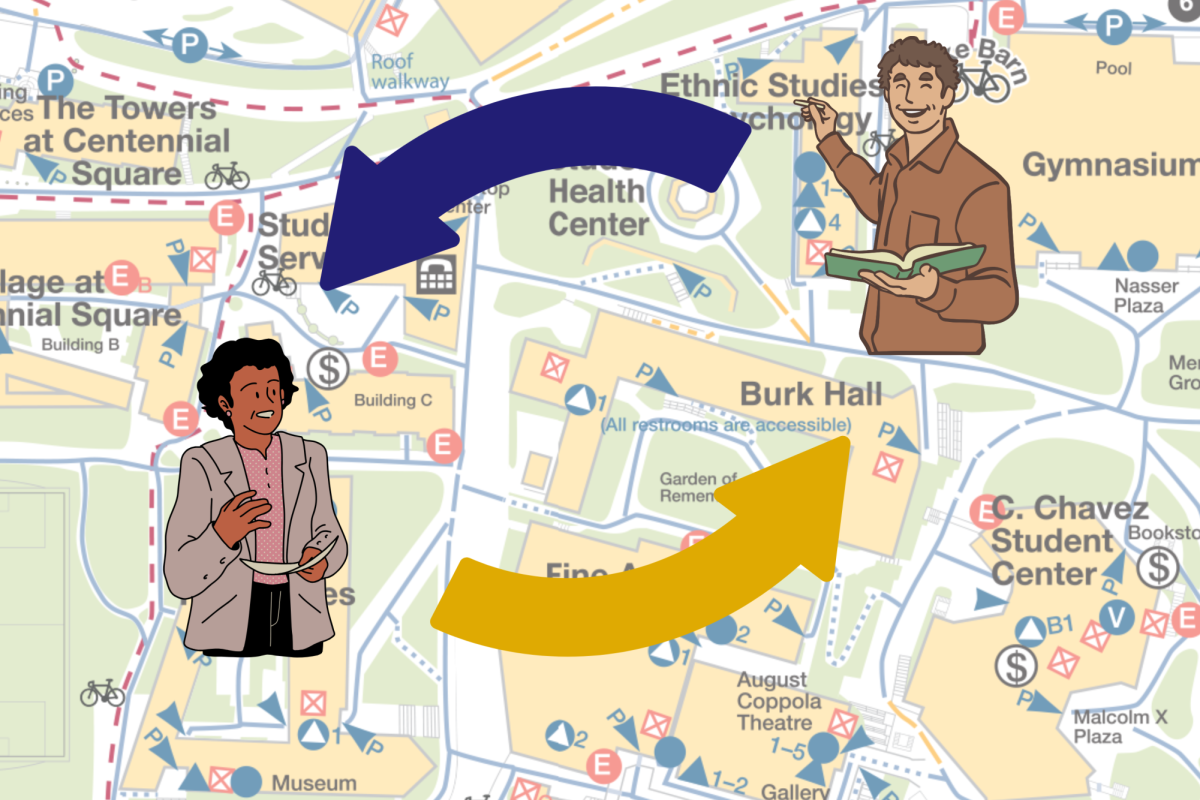

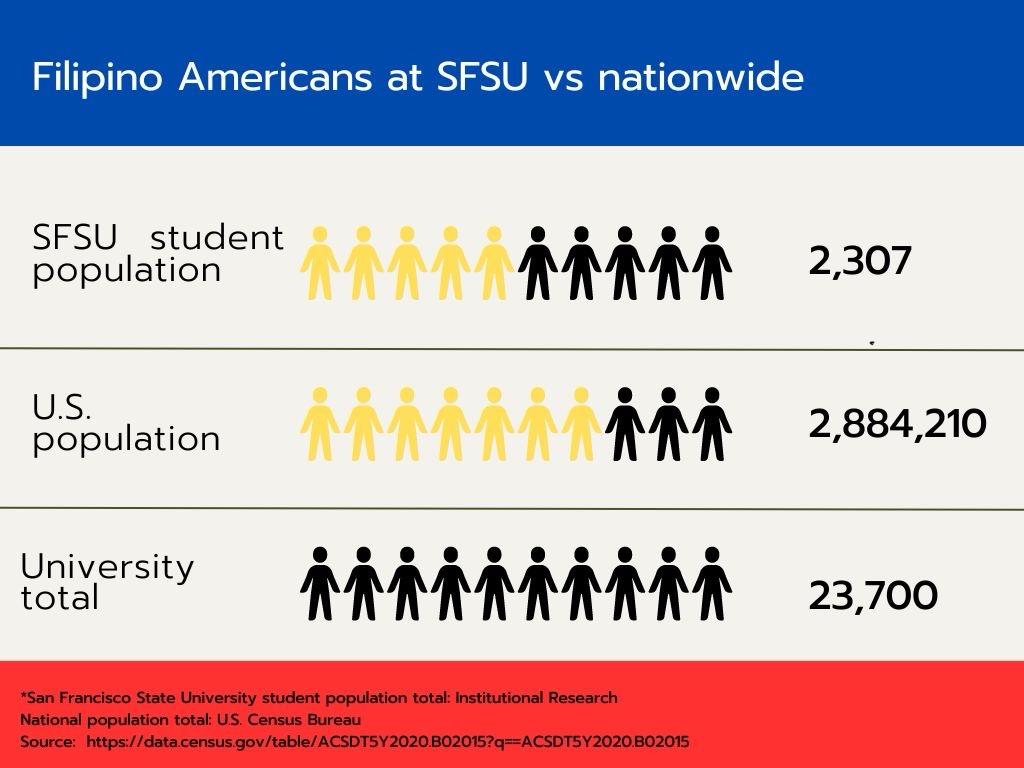

At San Francisco State University, Institutional Research counted a student population of 23,700.

Of those 23,700 students, the total numbers for enrolled undergraduates as of Fall 2023 are as follows: 2,307 Filipino American students, 1,676 Chinese Americans and 632 Vietnamese Americans.

Valerie Fernandez is a lecturer in the Asian American studies department who goes by “Baba” among students and fellow faculty. She obtained her undergraduate degree in Philippine Studies from the University of San Francisco prior to beginning her doctoral degree at SFSU.

She says the higher rates of diabetes in the Filipino American community is due to the effects Western interference had on indigenous food systems.

“Two words — colonization and imperialism — had a huge influence on the Filipino diet. When the Philippines was colonized by Spain, that was the introduction to pork,” Fernandez said.

When the Spanish introduced pigs into Filipino culture as part of the galleon trade, pork had not existed in the Filipino diet. According to Fernandez, Filipino food became very meat-focused and much of the Filipino food eaten today is rich with grease and fat. Fernandez said canned food and white sugar were also introduced into the Filipino diet during this time.

Fernandez said that diabetes is so prevalent in the Filipino American community that she viewed a diagnosis as being a foregone conclusion.

“Growing up I thought diabetes, to be quite frank, was like the flu because it was so common to hear that — like, everybody gets the flu, everyone’s gonna get diabetes,” Fernandez said.

There are several Bay Area-based health organizations aimed at combating health inequity within the Filipino American community. The Mabuhay Health Center is a student-based and volunteer-run health center founded in 2009 at the University of California, San Francisco and based in the South of Market neighborhood.

According to finance director Mikhail Alejandro, students from medical or dental departments offer health screenings, among other services. The center also collaborates with SFSU’s physical therapy program.

Alejandro says much of the demographic the center caters to are individuals who live in single-room occupancy housing, many of whom are elderly or who make less than $20,000 annually. Mabuhay Health Center also collaborates with local organizations like the Filipino American Development Foundation.

“One of the things that we’ve been really pushing for, especially with it being [AAPI Heritage] month, are going out to all these events, like festivals or things like that, tabling, providing health education,” Alejandro said. “Sometimes we’ll be able to offer certain screenings — blood pressure checks, vitals, and, not now obviously, but flu shots when needed. It really just depends on the capacity that UCSF is willing to give us.”

“A long-term goal is to be a pillar in the community and resource, especially [to those] who do not have access to these health services and screenings,” Alejandro said. “Another goal is to expand our outreach. Because we do cater to [a] dominantly elderly community, [but] we want to help everyone that is facing financial burden and disparities.”

According to Alejandro, MHC founder Alvin Teodoro began the clinic upon witnessing health disparities in the SOMA neighborhood, which has a large Filipino American population due to immigration patterns. Alejandro said that the most common health issues staff have observed at the clinic are related to cardiovascular health, which he said is due to several factors, primarily diet.

“It’s always cardiovascular health. Because that’s typical; if you take into account Filipino culture, our food isn’t necessarily the healthiest,” Alejandro said. “So, I mean, there’s always high blood pressure; constraints of hypertension [and] diabetes are two prominent issues that we’ve seen.”

Alejandro said that clinic staff has observed several factors that make healthcare access an ongoing struggle for the people in the area.

“Two social determinants come into mind — access itself, because transportation sometimes might be an issue for our community members,” said Alejandro. “One thing that really messes with our clinics is if it rains, because if it rains, most of the elderly take public transportation to get here.”

Alejandro also said that there is a language barrier between staff and non-English speaking clinic visitors, although he added that MHC has a committee dedicated to translating information and material to Tagalog, the most common Filipino dialect. He added that MHC was also recently approved by UCSF to begin distributing needs assessment surveys as an interactive way to gauge community needs.

“One of the things that make[s] MHC unique is that we take into account cultural sensitivity when treating our community members,” Alejandro said.

At SFSU, Filipino American students expressed their own personal experiences with health inequity in their community.

Isabellah Finuliar is a child development major minoring in special education and queer and trans ethnic studies.

She seemed unsurprised to hear that diabetes affects the Filipino American community at higher rates, attributing this phenomenon to flawed healthcare infrastructure.

“Whether it’s conscious or not, I feel like they established this kind of model to follow when providing Asians healthcare and doing these certain practices. And with that in mind, I think at the end of the day, a lot of our institutions are built on whiteness, and seeing whiteness as an ideal, which is another big issue at hand,” Finuliar said. “And I personally think that with that foundation of whiteness in mind, I do think that people with language barriers and people who belong to minority groups tend to be left behind because they do not fit that model — and the closest groups that fit to that model are people with fair skin, people who speak English only, people who are able-bodied and people who are cisgender-heterosexual too.”

Finuliar said that her own family has expressed discomfort with the American healthcare system due to lack of what she called cultural competency.

Taking a class about Latino healthcare perspectives during her first year at SFSU opened her eyes to healthcare disparities affecting POC communities, which she said made her aware of the inequality within her own.

Finuliar said that she wasn’t aware until several years ago the extent her community, and by extension herself, had internalized those racial stereotypes.

“I guess taking that class was really kind of that catalyst that allowed me to understand what was going on — not just in my immediate household, but also my community too,” Finuliar said.

Finuliar, who also teaches elementary school children, has witnessed firsthand the ways young children have become more aware of disparities within their community — even if they don’t have the language to describe it.

“I do think that the younger population does have knowledge that, something’s up — like, why is my community more affected than other communities around me? Why am I seeing this more in my communities?” Finuliar said. “I think it’s just that they need to be given the language, the knowledge and the frameworks to kind of define exactly what’s going on in their minds. Because once they’re given the language to really define their personal experiences, then they’re able to transform the world.”

Finuliar is not the only student to share similar feelings. Malay Castillo was born in the Philippines and immigrated to the United States at 16. He is a communications major minoring in Race and Resistance Studies.

He is a member of the League of Filipino Students, a grassroots organization centered around workers’ rights and student activism. He said that he has seen in his activist work that Filipino Americans may be unaware of health disparities in their community because many of them remain unengaged with issues inside the community.

“What I observed is most of the time people who are of better economic backgrounds are a lot harder to mobilize; there’s a level of ignorance that these people have. And also I feel being in America, I feel regardless of your economic background, I feel like there’s this urge to assimilate,” Castillo said. “Mainly because it’s the dominant culture and of course, a lot of people want to be a part of something; they want to feel included into something and that attributes to a lot of — kinda like erasing an identity.”

Prior to moving to America, Castillo hadn’t anticipated such stark cultural differences between Filipinos in the mainland and in the United States.

“I wanted to be a part of their community too, because I saw them as other Filipinos just like me, but then definitely I was also caught in this whole notion of the American Dream,” Castillo said. “I was an America stan before I came. I was like, ‘Hell yeah, I get to go to America!’ Like, better opportunities, you know? Like, ‘Yeah, I’m leaving my family and friends or whatever, but then I get to live in a better place.’”

It was the American higher education system that broke that fantasy for him.

“The moment I hit college, and then the moment I started learning more and getting higher education, finding mentors that helped me realize and decolonize myself — and I’m still going through that decolonizing process,” Castillo said. “I’m realizing now that everything in my life is connected to American imperialism and just politics in general.”

Castillo said that mobilizing Filipino Americans around issues of social justice is traditionally an arduous task for LFS members. Part of it is due to community members being preoccupied with school, work, or family, he said. But the issue also runs deeper — many people simply don’t view community struggles as being their problem.

“Some people maybe just don’t want to do it and they’re thinking that they could spend their time better hanging out with friends — there’s a lack of urgency,” Castillo said. “Unless it starts to affect them then it doesn’t really matter.”

Nevertheless, Castillo said he maintains hope that the tides are turning and Filipino Americans are increasingly becoming more politically conscious, a pattern he again attributes to the American education system.

“I think access to information is a lot easier and a lot more accessible,” Castillo said. “Any youngster that gets into wanting to learn more about, let’s say, the history of colonial America, then it’s very easy for them… I would say there’s seeds that are being planted better now in young people to kind of be more critical about what their lived experiences are and how that connects to the bigger community, [but] you have to be willing.”

Read part two of this series: https://goldengatexpress.org/107116/campus-original/chinese-americans-still-reeling-in-the-wake-of-anti-asian-hate/

Read part three of this series: https://goldengatexpress.org/107114/campus-original/vietnamese-americans-have-higher-rates-of-liver-cancer-compared-to-other-asian-american-subgroups-why/